Our Value-Based Cup Runneth Over

By Daniel Reck, Samuel Johnmeyer and Lisa Swan

Health Watch, September 2022

Five years ago, value-based contracts (VBCs) were new, fun, exciting and can-we-just-sign-a-contract-already-so-we-can-start-changing-health-care? These days, population health actuaries working for health systems are up to their eyeballs in value-based contracts. The authors work for a regional health system and are responsible for the performance of 42 VBCs—or is it 43? Honestly, we’re not sure. (We just looked it up. It’s 37.) To make things more complicated, each contract has a different definition of trend, uses a different risk adjustment methodology, applies a different patient attribution logic, includes different quality measures and covers different networks. Each payer has a unique relationship with the system, with different degrees of reporting, engagement and collaboration. These intricacies are overwhelming. So while we recognize any given contract may be using a state-of-the-art, peer-group-adjusted credibility factor for 150 members, the stakeholders need to spend less time deciphering contract details and more time driving improved outcomes for the members.

Don’t get us wrong, we (the health system actuaries working on value-based care) love this work. And we all have the same objectives—higher quality care, healthier populations and lower costs. We also believe value-based contracting has become so complex that it is hard to see the forest for the trees. It is time for value-based contracting to mature. Health plan actuaries, please consider this our cry for help. Specifically, there are three areas where we would love to work with our health plan actuary partners to improve value-based contracts:

- Consistency. We love risk adjustment. Just love it. We usually start our days talking about how much we love risk adjustment. But we also have a hard time explaining to our physician partners why we are being measured with 12 different risk adjustment models depending on the payer and line of business. It is time for more consistency between contracts!

- Predictable revenue. It is hard to overstate how much COVID-19 has impacted health care providers. From staffing challenges and soaring input costs to pandemic wave–influenced revenue volatility, providers are navigating choppy waters. One area where actuaries can help providers is by advocating for predictable revenue streams in value-based contracts.

- Risk assessment. Large swings in interim reported performance may be driven by small changes in claims trend, risk adjustment or other contract parameters. We have an opportunity to help providers understand the impacts of leveraging on expected VBC revenue through scenario testing, probabilistic modeling and risk appetite.

Consistency

As an example of the consequences of inconsistency across value-based contracts, let’s dive into one important piece of these arrangements: measuring quality. “Quality” means many things to many people, so we want to be clear that we are not advocating for any specific quality measures or methodologies. However, quality is a critical component of value-based contracting, and one thing that is often surprising to those outside the health care industry is the malleability of quality. For example, flu shots. Measuring flu shots seems like an easy thing, but two things need to happen to score high on the flu shot quality measure:

- Your patients need to get flu shots.

- You need to prove that your patients received flu shots.

It sounds simple, but documenting and proving your quality score requires time, effort and investment. Taking this example further, let’s say we have revenue tied to our flu shot performance, and the bonus revenue is based on us achieving a 91 percent flu shot rate. Furthermore, we know 95 percent of our members received a flu shot, but we can only prove 90 percent received one. To get our flu-shot bonus, we need to prove an additional 1 percent of our patients received a flu shot. Are we better off trying to get the last 5 percent of our patients to get a flu shot or performing better documentation on the 5 percent who had a flu shot but substandard documentation? The answer itself does not matter as much as the fact that we must do this type of cost-benefit analysis for 53 quality measures. Because yes, we have 53 different quality measures we are responsible for hitting across our 37 value-based contracts.

Lest you think this is isolated to our experience, reducing complexity is a major tenet of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Innovation Center’s (CMMI’s) road map. In October 2021, CMMI posted a white paper on its value-based modeling efforts since 2010. This paper outlines lessons learned from the past decade and CMMI’s vision for the future. Over the last 10 years, CMMI launched more than 50 model tests, of which only a handful were expanded beyond the test phase. Innovation requires testing to progress, but the complexity of these models have increased administrative burden and undermined model effectiveness.[1] Bringing this back to our health plan partner actuaries, who may be thinking, “I wanted to read this wonderful article to learn more about being an actuary, and here I am being lectured about quality scores. I don’t have anything to do with quality scores!” To which we would respond: first, consider getting your flu shot. Second, you might not have direct control over quality measures, but you do have control over many other parameters. Our request to health plan actuaries is this: when setting parameters for value-based contracts, come to the table with an open mind and options.

As provider actuaries, we should maintain a regularly updated inventory of contract details. We should speak up more often in joint operating committee meetings to improve alignment in measurement methodology across contracts. We should devote more of our time to raising awareness and education within the organization on the distinction between the different types of risk adjustment models, quality measures and financial parameters. This will ensure less time is spent discussing differences in contracts and more time is available to physicians to engage and manage the quality and cost of care for their patients. To summarize:

- What can provider actuaries do to improve consistency? Take inventory, speak up and advocate for consistency.

- What can health plan actuaries do to improve consistency? Bring an open mind and options to the negotiating table.

Whether quality measurement, risk adjustment models, risk adjustment application or transparency of reporting, our patients/members will benefit from some industry standards. Let’s spend less time tweaking parameters and more time improving outcomes for our ultimate stakeholders.

Predictable Revenue

As providers face some of the most significant financial challenges in recent memory, the ability to increase accuracy in projected revenue is crucial. Capacity issues along with rising input costs have stressed the financial sustainability of health care providers. From a report by the American Hospital Association in April 2022, when comparing 2021 to 2019, we see the following[2]:

- Labor expenses per patient increased 19 percent.

- Total supply expenses per patient increased 21 percent.

- Hospital drug expenses per patient increased 37 percent.

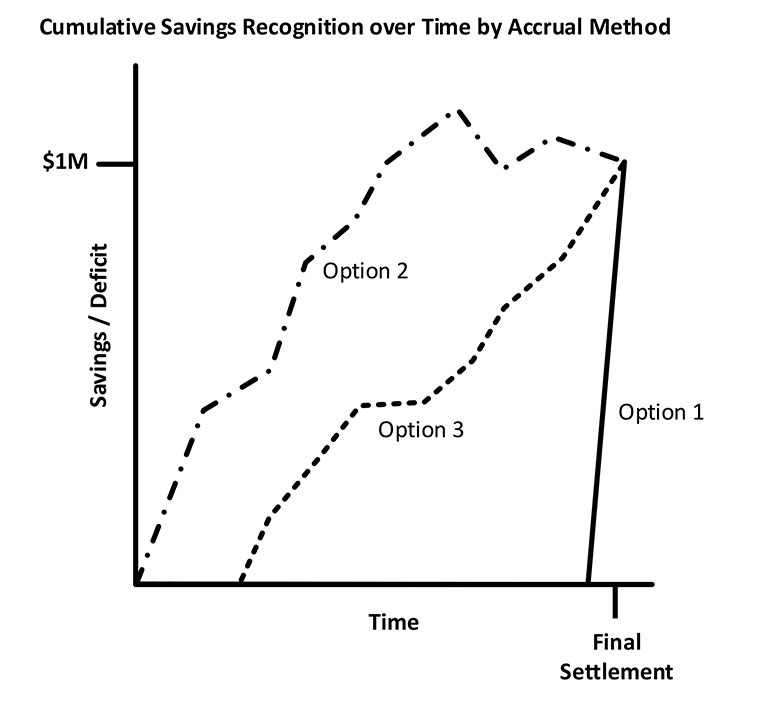

When large provider groups create budgets and update financials, they have a decision to make regarding VBC revenue. Typically, they have three choices:

- Assume no savings or loss for the contract until final settlement.

- Use payer estimates from interim reports to set accruals throughout the year.

- Use in-house financial modeling and projection work to set accruals throughout the year.

Each of these approaches present different challenges. With option 1, the provider group may see a large, one-time impact to their financials six to nine months after the end of the performance year. This may occur more than a year after budgets were created for the year of payment receipt. Instead, imagine that impact had been known when budgets were set. This information could have significantly altered the provider group’s decisions around staffing or infrastructure investments.

Option 2 relies on the payer to set appropriate assumptions. These may be inherent assumptions, such as the incurred but not reported (IBNR) or seasonality adjustment. The details of these applications are often absent in payer reporting or foreign to provider finance analysts. It is important for health plan actuaries to consider that their work may be used in this way and provide appropriate communication around the results shared.

Option 3 may be challenging for those providers who don’t have access to their own actuaries. Additionally, the ability to accurately project is dependent on the data shared by the payer. Claims paid outside of the provider system are often proxied or blinded before they are shared.

Figure 1 provides an illustration of an accountable care organization (ACO) that achieved $1 million in savings and how the provider group may cumulatively recognize that revenue under each option over time. We’ll assume that the provider group is more conservative in their risk appetite than the underlying assumptions in the payer reporting may reflect, leading to smaller accruals throughout the performance year.

Figure 1

Given these challenges faced by providers related to revenue predictability, what can we do? Absent jumping to a fully integrated health plan, the endgame of predictable revenue would be full capitation. Provider readiness for full capitation on VBC populations may be premature, but now is the time to explore creative solutions to bridge the gap. One way to increase revenue predictability is to move to a subcapitation model. Primary Care First and Direct Contracting have tested this in the Medicare population with varying levels of success. To summarize:

- What can provider actuaries do to improve revenue predictability? Educate your organization on the trade-off between predictable revenue and upside.

- What can health plan actuaries do to improve revenue predictability? Advocate for subcapitation or percent of premium arrangements.

Whether its subcapitation for certain well-defined service lines or creative approaches to bundles, these types of ideas can be incorporated into current value-based contracts to help increase revenue predictability for providers when they need it most.

Risk Assessment

Imagine, here we are at the beginning of the year. The ink is not yet dry on a new contract, and both parties are ecstatic. Providers are happy because we have simplified, consistent model parameters as well as a new, predictable revenue stream. Payers are happy because they have great rates for a partner willing to increase quality, reduce costs and improve the health of their members. It’s working. We did it, everybody!

Fast forward to July. We just received a monthly performance report and things are not looking good. In June, we had $25 per member per month (PMPM) in savings, then one month later, it’s down to $20 PMPM, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Theoretical Monthly Performance Report Showing PMPM Savings

|

Measure |

June Report |

July Report |

Trend |

|

PMPM |

$475 |

$480 |

1% |

|

PMPM goal |

$500 |

$500 |

N/A |

|

Savings |

$25 |

$20 |

–20% |

Any actuary would look at this table and say, “Ah yes, leveraging.” Since providers often don’t have access to their own actuaries, insurance companies are uniquely qualified to help providers better understand their contracts. Providers get a ton of reporting from insurers. Each insurer provides its own reporting package, and they all differ in what they include. It is helpful to work together to establish an appropriate reporting cadence and to thoroughly document what goes into the reporting. Reports can include IBNR, be seasonally adjusted, account for stop-loss, report on a rolling 12 or year-to-date (YTD) basis—the list goes on. It is difficult for providers to keep track of the differences, and these nuances are often not well documented. Some providers might have a preference for how the data are presented, so having these conversations can help create more meaningful reporting.

As shown above, seemingly small changes in risk score or claims trend can translate into large swings in the financial performance of the VBC. More advanced reporting, such as scenario or simulation modeling, can help providers understand how risky the financial agreement truly is. Understanding how sensitive the financial performance is to various inputs can help providers figure out where to focus their efforts as well as prepare leadership for financial variability month after month. To summarize:

- What can provider actuaries do to improve risk assessment? Provide a range or distribution of projected outcomes to leadership.

- What can health plan actuaries do to improve risk assessment? Incorporate scenario or sensitivity testing in payer reporting.

By moving from deterministic to probabilistic reporting, we can help health systems better understand the nature of these contracts. This can help improve health care sustainability by allowing provider leadership to make more informed financial decisions based on their risk appetite, rather than on the risk appetite embedded within assumptions in reporting.

Conclusion

There are health care providers who want to participate in value-based contracts but simply don’t have the resources. Health plans can become partners in this space and help providers make the transition to value-based care. Standardizing contracts, making revenues more predictable and providing more thorough reporting packages are just some of the ways insurance companies can support providers. Success in value-based contracts is challenging, even ignoring the contracting complexities that come with them. Through these partnerships, providers and payers can work toward achieving the triple aim of higher quality care, healthier populations and lower costs.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Daniel Reck, FSA, MAAA, is a director at Multicare Connected Care. Dan can be reached at Daniel.Reck@multicare.org.

Samuel Johnmeyer, FSA, MAAA, is a director at Multicare Connected Care. Samuel can be reached at Samuel.Johnmeyer@multicare.org.

Lisa Swan, FSA, MAAA, is a director at Multicare Connected Care. Lisa can be reached at Lisa.Swan@multicare.org.