By Alicia H. Munnell

Editor's Note: This article was previously published by The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. It is reprinted here with permission

Introduction

Since working longer is the key to a secure retirement for the vast majority of older Americans, it is useful to take a look at labor force trends for those under and over age 65 for the last century.

This brief proceeds in three steps. The first section describes the long-run decline in labor force participation of men. The second looks at the turnaround that began in the mid-1980s. The third section discusses the trends for women, which combine their increasing labor force activity, on the one hand, and incentives to retire, on the other.

The final section concludes that labor force activity of both men and women has increased significantly since the mid-1980s as many incentives now encourage work. Several hurdles remain to continued increases, however, including the sluggish economic recovery, the move away from career employment, the availability of Social Security at 62, and employer resistance to part-time employment.

The Long-term Decline in Employment Rates

The notion of retirement as a distinct and extended stage of life is a recent innovation. Up to the end of the 19th century, people generally worked as long as they could. In their prime, they put in 60 hours of work each week. And, at the end of their lives, they had only about two years of 'retirement,' often due to ill health.1

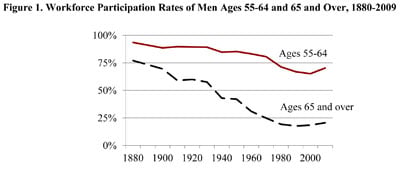

Beginning around 1880, the percentage of the older male population at work began to decline sharply (see Figure 1). Experts attribute this decline to an unexpected and substantial stream of income that appeared in the form of old-age pensions for Civil War veterans. A comprehensive study found that veterans eligible for these pensions had significantly higher retirement rates than the population at large.2

Note: Work rates during 1880-1930 are any reported gainful occupation. In the period 1940-2009, work rates are labor force participation rates, defined as working or seeking work.

As the veterans died off, work rates did not return to their previous levels. Various analysts argue that this trend reflects the growth of workers' incomes.3 But employer attitudes were also becoming important. The U.S. workforce was rapidly shifting from self-employment, most notably in agriculture, to employees of large enterprises. Employers increasingly introduced mandatory retirement ages for their employees. And they were reluctant to hire older workers, especially during the Great Depression.4

The next big decline in the work rates of older men occurred after World War II. One obvious factor was the availability of Social Security benefits. The legislation was enacted in 1935; Old Age welfare benefits were paid almost immediately and Social Security retirement benefits began in 1940. The postwar period also saw the expansion of employer pensions, as union power grew and corporations increasingly saw pensions as a crucial component of their personnel systems.

The introduction of Medicare in 1965 and the sharp increase in Social Security benefits in 1972 probably led to the final leg of the decline in workforce activity of older men. And, because benefits were available at 62, Social Security may also explain part of the decline in workforce activity for men 55-64.

The Recent Reversal

The downward trajectory stopped around the mid-1980s, and since then the labor force participation of men both 55-64 and 65 and over has gradually increased. Many factors help explain this turnaround.5

- Social Security: Changes to Social Security made work more attractive relative to retirement. The liberalization, and for some the elimination, of the earnings test removed what many saw as an impediment to continued work.6 The delayed retirement credit, which increases benefits for each year that claiming is delayed between the Full Retirement Age and age 70, has also improved incentives to keep working.7

- Pension type: The shift from defined benefit to 401(k) plans eliminated built-in incentives to retire. Studies show that workers covered by 401(k) plans retire a year or two later on average than similarly situated workers covered by a defined benefit plan.8

- Education: People with more education work longer. Over the last 30 years, education levels have increased significantly, and the movement of large numbers of men up the educational ladder helps explain the increase in participation rates of older men.9

- Improved health and longevity: Life expectancy for men at 65 has increased about 3.5 years since 1980, and–despite the growth in the number of individuals receiving Disability Insurance benefits–much of the evidence suggests that people are healthier as well.10 The correlation between health and labor force activity is very strong.

- Less physically demanding jobs: With the shift away from manufacturing, jobs now involve more knowledge-based activities, which put less strain on older bodies.11

- Joint decisionmaking: More women are working; wives on average are three years younger than their husbands; and husbands and wives like to coordinate their retirement. If wives wait to retire until age 62 to qualify for Social Security, that pattern would push husbands' retirement age toward 65.12

- Decline of retiree health insurance: Combine the decline of employer-provided retiree health insurance with the rapid rise in health care costs, and workers have a strong incentive to keep working and maintain their employer's health coverage until they qualify for Medicare at 65.13

- Non-pecuniary factors: Older workers tend to be among the more educated, the healthiest, and the wealthiest.14 Their wages are lower than those earned by their younger counterparts and lower than their own past earnings. This pattern suggests that money may not be the only motivator.

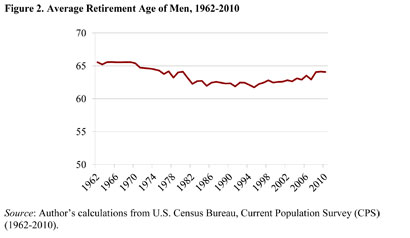

As a result of these various factors, the average retirement age for men has increased from 62 to 64 over the last 20 years (see Figure 2 on the next page). The average retirement age is defined as the age (in years and months) at which the labor force participation rate drops below 50 percent.15

The Case of Women

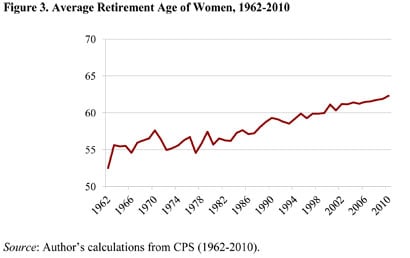

Determining trends in the average retirement age for women is much more complicated, because women's work patterns reflect the increasing participation of cohorts over time as well as the factors that affect retirement behavior. The challenge is evident in Figure 3, which depicts the average retirement age for women.16 The figure suggests that the retirement age rose dramatically from 55 in the 1960s to 62 in 2010. Of course, the apparent low retirement ages in the early 1960s simply reflect the fact that few women had spent much time in the labor force.

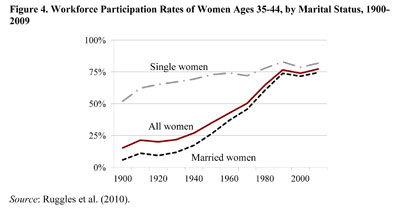

The role of women changed enormously over the 20th century, and these changes had a profound effect on their labor force participation (see Figure 4). In turn, the transformation of women's employment during their prime years (35-44)–particularly the increased labor force participation of married women–sharply affected their labor force activity when they were older. Each cohort of women 55-64 had spent more time in the labor force than the previous cohort, increasing the likelihood that they would be working at older ages.

At the same time, older women were subject to many of the incentives to retire early faced by men. They were eligible for Social Security benefits at age 62 beginning in 1956. They faced a stiff Social Security earnings test and lost lifetime benefits if they worked beyond age 65. They enjoyed the enactment of Medicare in 1965 and the sharp increase in Social Security benefits in 1972 to roughly a 40-percent replacement rate for the benchmark average earner. In contrast to men, because fewer women were covered by traditional employer defined benefit plans, their labor-supply decisions were not significantly affected by the early-retirement subsidies such plans offered.

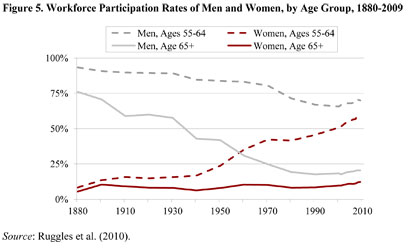

These conflicting forces–the changing role of women and the shifting incentives to retire early–may help explain the pattern in the labor force participation of women age 55-64 (see Figure 5). Until about 1950, less than 20 percent of women in this age group were in the labor force. Between 1950 and 1970, the percentage doubled to more than 40 percent. But then beginning in 1970, just as the male rate began to decline noticeably, older women's labor force participation leveled out, possibly the result of offsetting cohort effects that increased participation and incentive effects of Social Security and pensions that encouraged retirement.

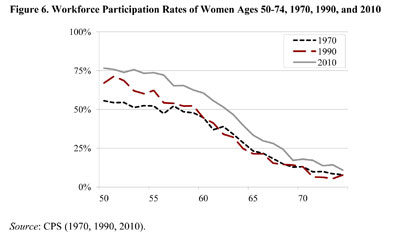

Beginning in the mid-1980s, the labor force participation of women 55-64 renewed its upward trend. By 2010, about 60 percent of these older women were in the labor force. Part of this increase may reflect the shift in incentives in Social Security, such as the increase in the delayed retirement credit and the relaxation of the earnings test (and elimination for those over the Full Retirement Age), the declining importance of the early retirement incentives in defined benefit plans, and the need to work until eligible for Medicare given the decline in employer-provided retiree health insurance and the rapidly rising costs of health care. But large increases also occurred among women under 60, which suggest that the cohort effect–that is, the increasing participation of women at younger ages–may also be playing an important role (see Figure 6).

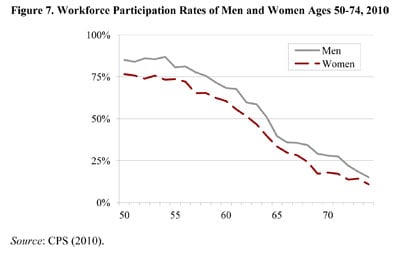

In any event, the labor force participation of older women is now close to that for older men (see Figure 7). And the average retirement age of 62 shown in Figure 3 is probably an accurate portrayal of women's retirement patterns.

Conclusion

The labor force activity of both men and women has increased. In the case of men, this increase reflects the fact that many incentives now encourage work. In the case of women, two forces have been at play–the changing role of women and its impact on labor force activity and the same incentive factors affecting men. At this point, the average retirement age for men is 64 and for women 62.

Will the retirement age continue to increase? The fact that all the incentives associated with the recent reversal will remain in place argues for "yes." But there are risks–the move away from career employment, the availability of Social Security at 62, and employer resistance to part-time employment.

Alicia H. Munnell is the director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College and Peter F. Drucker Professor of Management Sciences in Boston College's Carroll School of Management.

Endnotes

1 Thane (2000); and Sass (1997).

2 Costa (1998).

3 Costa (1998).

4 Moen (1987); Margo (1993); and Sass (1997).

5 Friedberg (2007); Burtless and Quinn (2002); and Munnell and Sass (2008).

6 Engelhardt and Kumar (2007); and Friedberg and Webb (2006).

7 Song and Manchester (2007); and Kopczuk and Song (2008).

8 Friedberg and Webb (2005); and Munnell, Cahill, and Jivan (2003).

9 Munnell and Sass (2008).

10 U.S. Social Security Administration (2011); and Munnell and Sass (2008).

11 Johnson (2004).

12 Schirle (2007).

13 Gustman and Steinmeier (1994); Karoly and Rogowski (1994); Rust and Phelan (1997); and Monk and Munnell (2009).

14 Lahey, Kim, and Newman (2006); and Maestas (2005).

15 This methodology evolved from that of Burtless and Quinn (2002) who take the youngest age, in years, at which at least half of men have left the labor force. They calculate the labor force participation rate by age and average over two-year periods (i.e., 1962 and 1963). Our calculations differ in that the results are annual and interpolated to calculate the age in terms of years and months.

16 Because the labor force participation rate for women drops below 50 percent several times, the average retirement age was defined as the last age at which it fell below 50 percent.

References

Burtless, Gary and Joseph F. Quinn. 2002. "Is Working Longer the Answer for An Aging Workforce?" Issue in Brief 11. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Costa, Dora L. 1998. The Evolution of Retirement: An American Economic History, 1880-1990. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Engelhardt, Gary V. and Anil Kumar. 2007. "The Repeal of the Retirement Earnings Test and the Labor Supply of Older Men." Working Paper 2007-1. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Friedberg, Leora. 2007. "The Recent Trend Towards Later Retirement." Work Opportunities for Older Americans Series 9. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Friedberg, Leora and Anthony Webb. 2005. "Retirement and the Evolution of Pension Structure." Journal of Human Resources 40(2): 281-308.

Friedberg, Leora and Anthony Webb. 2006. "Persistence in Labor Supply and the Response to the Social Security Earnings Test." Working Paper 2006-27. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Gustman, Alan and Thomas Steinmeier. 1994. "Employer-Provided Health Insurance and Retirement Behavior." Industrial and Labor Relations Review 48(1): 124-40.

Johnson, Richard. 2004. "Trends in Job Demands among Older Workers, 1992-2009." Monthly Labor Review 127(7): 48-56.

Karoly, L. A. and J. A. Rogowski. 1994. "The Effect of Access to Postretirement Health Insurance on the Decision to Retire Early." Industrial and Labor Relations Review 48(1): 103-23.

Kopczuk, Wojciech and Jae Song. 2008. "Stylized Facts and Incentive Effects Related to Claiming of Retirement Benefits Based on Social Security Administration Data." Working Paper WP-2008-200. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Retirement Research Center.

Lahey, Karen E., Doseong Kim, and Melinda L. Newman. 2006. "Full Retirement? An Examination of Factors That Influence the Decision to Return to Work." Financial Services Review 15(1): 1-19.

Maestas, Nicole. 2005. "Back to Work: Expectations and Realizations of Work after Retirement." Working Paper WR-196-1. Santa Monica, CA: Rand.

Margo, Robert A. 1993. "The Labor Force Participation of Older Americans in 1900: Further Results." Explorations in Economic History 30(3): 409-23.

Moen, Jon R. 1987. "Essays on the Labor Force and Labor Force Participation Rates: The United States from 1860 through 1950." Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago.

Monk, Courtney and Alicia H. Munnell. 2009. "The Implications of Declining Retiree Health Insurance." Working Paper 2009-15. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Munnell, Alicia H., Kevin E. Cahill, and Natalia Jivan. 2003. "How Has the Shift to 401(k)s Affected the Retirement Age?" Issue in Brief 13. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Munnell, Alicia H. and Steven A. Sass. 2008. Working Longer: The Solution to the Retirement Income Challenge. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Ruggles, Steven, J. Trent Alexander, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Matthew B. Schroeder, and Matthew Sobek. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2010.

Rust, John and Christopher Phelan. 1997. "How Social Security and Medicare Affect Retirement Behavior in a World of Incomplete Markets." Econometrica 65(4): 781-831.

Sass, Steven A. 1997. The Promise of Private Pensions: The First Hundred Years. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Schirle, Tammy. 2007. "Why Have the Labour Force Participation Rates of Older Men Increased since the Mid-1990s?" Working Paper. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University, Department of Economics.

Song, Jae and Joyce Manchester. 2007. "Have People Delayed Claiming Retirement Benefits? Responses to Changes in Social Security Rules." Social Security Bulletin 67(2).

Thane, Pat. 2000. Old Age in English History: Past Experiences, Present Issues. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1962-2010. Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Social Security Administration. 2011. The 2011 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

About the Center

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College was established in 1998 through a grant from the Social Security Administration. The Center's mission is to produce first-class research and educational tools and forge a strong link between the academic community and decision-makers in the public and private sectors around an issue of critical importance to the nation's future. To achieve this mission, the Center sponsors a wide variety of research projects, transmits new findings to a broad audience, trains new scholars, and broadens access to valuable data sources. Since its inception, the Center has established a reputation as an authoritative source of information on all major aspects of the retirement income debate.

Affiliated Institutions

The Brookings Institution

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Syracuse University

Urban Institute

Contact Information

Center for Retirement Research

Boston College

Hovey House

140 Commonwealth Avenue

Chestnut Hill, MA 02467-3808

Phone: 617.552.1762

Fax: 617.552.0191

Email: crr@bc.edu

Website: http://crr.bc.edu

The Center for Retirement Research thanks AARP, Bank of America, InvescoSM, LPL Financial, MetLife, MFS Investment Management, National Reverse Mortgage Lenders Association, Prudential Financial, Putnam Investments, State Street, TIAA-CREF Institute, T. Rowe Price, and USAA for support of this project.

The research reported herein was supported by the Center's Partnership Program. The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views or policy of the partners or the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.