By Mark Spong

By Mark Spong

It’s going very slowly, but ten years from now, it should be much easier for an actuary to move into what was previously considered an MBA-only role. That’s my stance on it.

-David W. Simpson, transcribed from SOA Washington Annual Meeting, October 1997

Mr. Simpson’s prediction from nearly 20 years ago highlights a major question that many actuaries consider at some point in their career: Should I get an MBA in addition to my FSA? Or will an FSA (along with experience and skill) qualify me to step into the types of business leadership roles that I look forward to?

Opinions vary widely and are largely dependent on personal circumstances. More and more actuaries are pursuing non-traditional roles and becoming entrepreneurs and innovators. The actuary of the future may be much more of a general business leader as Mr. Simpson predicted. The goal of this article is to aggregate those perspectives and sharpen our thinking as we consider if adding an MBA would make sense.

- Clarifying the Question

Before diving into arguments for and against adding an MBA, we should make a few things clear.

An MBA can mean many different things. It can mean two years studying full time at a very selective and prestigious institution. Executive MBAs can mean many months of night and weekend classes. Some MBA programs are offered entirely online.

The cost of an MBA varies just as widely. Full-time programs can cost several hundred thousand dollars when you take tuition and foregone salary into account. Executive MBA programs can be just as costly but a company sponsorship may be available.

With the variety of MBA options to consider, it is very likely that certain paths would be inappropriate while some others might make sense. To help make this distinction we should be explicit in selecting a set of “win conditions” that may justify the investment of time and money. For an MBA to be worth it, it should lead to:

- Greater impact,

- Expanded opportunities,

- Increased personal fulfillment, and

- Higher compensation.

The order may be subjective, but for an MBA to have any value it should have meaningful impact on the business. With the additional education, one should theoretically be able to step into more roles and take on greater responsibility. The last two conditions are certainly important, but are hollow and selfish motivations if the first two conditions are not satisfied.

- Arguments for adding an MBA

Non-actuarial MBAs are overwhelmingly positive about their MBA experience and the impact the degree had on their career. The alumni network is always stated as the primary benefit followed by executive presence training and general business knowledge playing a distant third. They often credit their first job (and salary bump) to their MBA program.

FSAs + MBAs also tend to be positive about their MBA experience. In 2009, Mark Sorenson and Jay Jaffe wrote an article for the SOA titled “ Is FSA enough?” and concluded that MBA programs offer a very attractive means of skills training and broader recognition required to compete and advance in a competitive and changing environment.

The perspective of actuarial students tends to be that they observe the impact that FSAs + MBAs business leaders have and naturally want to emulate that success. The Corporate Finance fellowship track is the most popular (~30 percent of FSA exam attempts according to actuarial-lookup.com), and has the most overlap with the MBA curriculum. For example, the primary source material for the CFE Exam is a textbook called Corporate Finance written by two Stanford Business School professors, and specifically focuses on applying risk management concepts beyond just insurance.

All three of these groups would argue that an MBA represents a broader base of knowledge and skills and is more publicly recognized as a leadership credential than a traditional FSA. Key uses for an MBA are:

- If you are in a top tier institution the recruiting process enables you to get your foot in the door at firms that might otherwise be closed.

- The network you build with classmates can help you change companies or industries and/or pivot roles. Those relationships can also be a long-term valuable asset to your company.

- The soft skills training may boost your presentation and communication skills and may make you a more effective manager and business leader.

- Arguments against adding an MBA

Experienced FSAs generally seem split in their opinion. Skeptics tend to point out the following:

- Business schools do not have a monopoly on self-improvement. A well-crafted personal development plan plus active and deliberate networking can yield the same kinds of benefits. Two intense years at a consulting firm would do more for polishing communication skills and enhancing executive presence than any number of case studies or classroom presentations.

- An FSA is a professional designation with certification and ethical standards (think quality control) whereas an MBA is not.

- The promise of a strong MBA alumni network is the result of highly successful marketing on the part of business schools, and is not a guarantee. Wide-eyed applicants buy this dream and pay a substantial premium for this intangible asset.

- One of the most attractive features of an actuarial career is that an FSA is sufficient. Candidates do not need fulltime graduate degrees. Pursuing an MBA would negate this relative advantage to other careers.

- If you don’t pursue an MBA-track role when you first complete the MBA, you may be squandering its value at its peak.

- As an FSA you already have your foot in the door in the industry and you don’t need an MBA to have an “in” with the top firms. In fact, it may even seem like recruiters will knock down your door once you earn your ASA or FSA.

Actuarial recruiters also tend to be skeptical of adding an MBA (see the recent DW Simpson article Pursuing an MBA as an Actuary – Is It Worth It?). The main drawback identified in the article is cost, which we can explore more on our own.

Suppose you earn your FSA and then take two years off to attend a top-five business school full time. You miss out on salary and incur substantial debt with the hope of landing a top paying job on graduation. How much does the salary boost have to be in order to balance out the cost of tuition and lost earnings?

The following hypothetical framework puts a career as an FSA on the left and an FSA plus MBA on the right. It makes some sweeping assumptions, but it is a start for an interested reader to personalize.

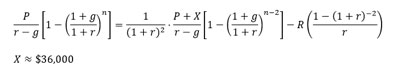

NPV(FSA Salary)=PV(NPV(FSA+MBA Salary))-NPV(Cost of MBA)

P=FSA Salary=$100,000

R=Annual Cost of MBA=$70,000

r=discount rate=10%

g=salary growth rate=3%

n=career length=30 years

X=Required Post MBA Salary Bump

This particular example requires a salary bump of $36,000 in the year after an MBA in order for the investment to break even.

At first this bump seems reasonable when compared to the headline of the Fortune article “ Congrats, MBA grads! You’re getting a $45,000 raise.” A second look shows the median starting salary for a newly hired MBA is about the same as an FSA without an MBA. Expecting the same boost in earnings on top of FSA compensation may be optimistic. A Wall Street Journal article noted in 2013, “ For Newly Minted MBAs, a Smaller Paycheck Awaits.” Even at Wharton, one of the best business schools in the world, the median salary in the Wharton Employment Summary for 2015 MBA grads is $125,000, still thousands less than the breakeven point for this example.

Aside from the cost, there are other considerations that are more subjective. The first is that designations can be very alluring. The attraction of additional letters to add to your signature and pad a resume can be incredibly strong. It is very important that a choice of this magnitude is not motivated by vanity. Earning an MBA on top of an FSA might be unconsciously equated to a golden ticket to the executive suite.

The second consideration is that there are several sources of bias that can warp our perception of the value that an MBA may add.

- Positive attribution bias may color the perspectives of MBAs. It would be difficult to admit that the time and money spent on earning an MBA was not worth it.

- Survivorship bias may sway observers to believe that the reason why MBAs often have more visible leadership positions than FSAs is because of their MBA. We may mistakenly ignore many other MBAs who were not as successful.

- Confirmation bias may lead people to favor an MBA because it is more widely known and marketed. If we expect MBAs to be successful business leaders, then that is what we are more likely to observe.

A third consideration is the differentiation factor. How much would adding an MBA set you apart from your peers? A quick look at the numbers may be surprising. There are just over 16,000 current FSAs in total ( SOA Analysis of Membership). To put this in perspective, more than 100,000 MBAs graduate every single year in the U.S. ( Graduate Management Admission Council). Harvard MBAs alone outnumber FSAs. While it is true that an FSA + MBA would be an even smaller and possibly more elite subset, there are plenty of other ways to distinguish your experience. For example, you might actively pursue lateral career moves for broader experience or stretch assignments in non-traditional roles. The point is that an FSA may be able take you farther than you think. After a decade on the job, odds are that your performance will be what distinguishes you as opposed to your credential.

- Conclusions

A common theme that came up during this research was branding. Perhaps it is not surprising that the degree that includes marketing and competitive strategy has clearly captured the public’s perception of leadership.

A company-sponsored Executive MBA turns out to be uniquely attractive to an FSA. It would satisfy all the identified win conditions in a way that other options may not. By partnering with your sponsor company, your impact on the business would be based on an independent assessment of real results, not just hopes and dreams. The investment in human capital by the sponsoring company would almost certainly be connected to strategic talent management goals and succession planning. The sponsoring company would cover all, or part, of the cost, which would be essentially equivalent to a raise. The partnership seems like a reasonable way for an FSA to further their personal and professional development while also meeting the needs of the business. Besides, would you rather network with proven business professionals whose sponsoring companies want to invest big money in them or bright, ambitious full time students just a few years out of school?

The goal of this article was to sharpen our thinking by presenting some perspectives and analysis. There are still a host of other questions to keep you up at night as you wrestle with deciding your path. As you do, remember Mr. Simpson’s prediction and consider Bob Morand’s reflection.

“The landscape has definitely changed since 1997. Actuaries have made themselves much more relevant for insurance companies. For example, the CRO title didn’t really exist back then. Actuaries have ascended to C-suite roles that used to be filled by MBAs. Looking forward another ten years, actuaries continue to reinvent themselves. Predictive Analytics is one area where actuaries continue to evolve and progress.”

–Bob Morand vice chairman, president & managing partner of D. W. Simpson

6/30/2016 Interview

Note: Thanks to the dozens of people who contributed their perspectives and helped shaped this article.

Mark Spong, ASA, CERA, is an actuarial associate with MassMutual. He can be contacted at mspong@massmutual.com.