By José Fidel Castañeda

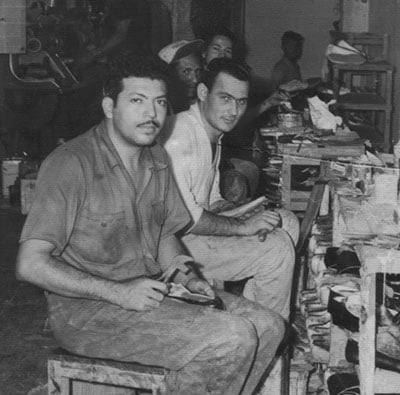

My father, José Bladimiro Castañeda (1929-2014), first up front, working in a small shoe factory in Venezuela (1959).

My father, José Bladimiro Castañeda (1929-2014), first up front, working in a small shoe factory in Venezuela (1959).

Has your family ever been in a cycle? Are you a cycle breaker? Like many others, I understand the difficulties of growing up in a challenging environment. I don’t know their personal circumstances, but we share a common bond even if we are separated by time, countries and circumstances. The bond is our desire to break "the cycle" and, for the readers of this newsletter, our actuarial education.

LIGHT AT THE END OF THE TUNNEL

Rational parents want the best for their children. Odd as it sounds, their harsh words and advice may spark the desire to go from “darkness to light.” Setting goals that require hard work and perseverance prepares children to look for the “light at the end of the tunnel.”

In my case, my parents expected that I would become a piecework laborer, making shoes at a local shoe factory, just as my father did from age 17 to age 70—he retired when he was unable to work anymore! I was 12 when he asked me to help him at the shoe factory. I did it for three summers during junior-high school. The experience gave me a taste of what my future could look like—it was sour! Occasionally, he asked me if I wanted my hands to become permanently calloused like his. I experienced hard manual work in a factory line, sitting side-by-side with my dad, helping him with his tedious and repetitive work—cobbling shoes at 500 pairs per week!

I think that my dad wanted to teach me a lesson at a very young age by giving me a front row seat to contemplate what could become my poverty cycle. Yet, perhaps without realizing it, the most significant lesson he taught me, by example, was how to become a tenacious, perseverant, honest, meticulous and passionate hard-worker. He also instilled in me grit to endure the monotonous conditions of an assembly line and a glimpse of what it was like to live with the sole purpose of getting through each day. He taught me the importance of being a strong performer, regardless of task.

IN THE YEARS TO COME, THERE WILL BE ENDLESS PILES OF SHOES

Money and resources may not be the best fuel to propel oneself to reach important goals and shape a determined and inspirational personality. I remember a well-to-do classmate asking why some students from the poor Caracas neighborhood where I was born were excellent actuarial students. My response was simple: “we want to break the poverty cycle.” This is why I enrolled at the Universidad Central de Venezuela. Students in my neighborhood—or any student, for that matter—didn’t need money to succeed. Hard work, persistence and steadiness of purpose were more than sufficient. As a student, I usually made my way to campus hitchhiking to spend 10 or more hours in classes and studying. Despite material scarcities, I obtained the highest GPA in our graduating class and became a certified actuary in a country where the total number of actuaries was about 100. In my opinion, studying is still one of the best ways to break the poverty cycle.

In the years to come, there will be endless piles of shoes, endless piles of actuarial projects, or endless piles of work, all of them necessary to put food on our tables. Let us face these challenges with the right attitude and respect.

THE SON OF A SHOEMAKER

Of course, breaking the poverty cycle does not mean that one becomes wealthy nor requires a college degree or an actuarial credential. By the same token, a job that requires performing repetitive tasks is not a marker of poverty. Let’s not forget this and if we manage to break the cycle let’s not lose sight of what feels like to be trapped in it with little hope.

In my case, the true cycle-breaker was my dad. He needed my help, yet, he gave me the opportunity to receive an education. At the end of those summers when I worked with him, he told me that I obtained the degree of “Shoemaker's Helper,” and that I should spend my time studying as long as I promised that I would not drop out of school. He saw the light at the end of the tunnel. His hard work inspired his many college-educated grandchildren, some of whom live in the United States! The legacy of José Bladimiro Castañeda, my dear old man, mi querido viejo, (1929-2014) is so valuable. At 12, I felt ashamed of his occupation; today it makes me proud to say that I am the son of a shoemaker.

José Fidel Castañeda, MAAA, is an international actuary, an entrepreneur, always looking to continue "making some shoes" to honor his dear viejo! He can be reached at www.us-actuary.com