Covid-19 Impact on the South African Life Insurance Industry: What Can we Learn?

By Idelia Hoberg

International News, July 2022

Background to the South African Life Insurance Industry

South Africa contains the largest insurance market in Africa, accounting for roughly 70 percent of the insurance premiums written across Africa. It is regulated through a Twin Peaks model, similar to the approach in the United Kingdom, which was implemented in 2018, establishing the authority of the Prudential Authority to regulate prudential matters and the Financial Sector Conduct Authority to regulate those requirements relating to market conduct. The new Insurance Act 2017 came into effect in July 2018 and established a prudential regulatory framework for insurers similar to Solvency II Pillar 1 and 2. However, disclosure requirements comparable to Solvency II Pillar 3 have not yet come into effect.

Furthermore, the Actuarial Society of South Africa (ASSA) and the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA) have historically had strong ties, with most actuaries in South Africa qualifying through IFoA prior to it being possible to qualify through ASSA. There are mutual recognition agreements for associates and fellows of ASSA with many internationally renowned actuarial societies.[1]

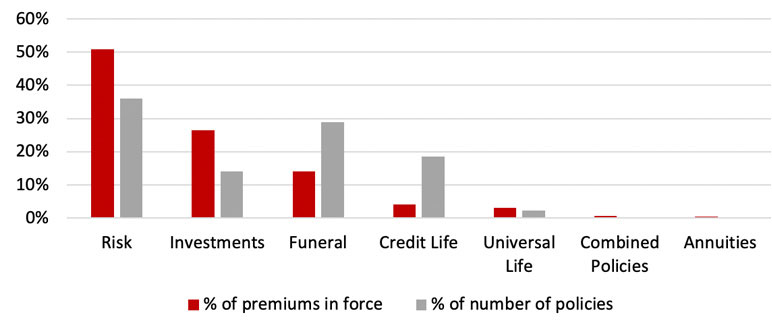

The South African life insurance industry is categorized by the large proportion of protection, or as it is locally called, risk business, which made up 69 percent of recurring gross written life premiums in force in 2021.[2] Risk business includes pure risk products covering death, disability or critical/severe illness, funeral products and credit life products. It is important to note that there is a discrepancy between the size of the market when considering number of policies vs premiums, as can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1

Market Share by Product Type

Please note: Number of policies includes Group business as number of schemes.

Of the total recurring gross written life premiums in force, 85 percent was for individual policies and 15 percent was for group policies.

An important aspect to consider when looking at the South African life insurance market, is the impact of socioeconomic inequalities in the country. As per the paper “Snakes and ladders and loaded dice: Poverty dynamics and inequality in South Africa, 2008–2017,”[3] during the observation, period 49 percent of South African households were chronically poor, 12 percent were categorized as transient poor (differentiated from the chronically poor based on their measured propensity to escape from poverty over time), 15 percent are in the vulnerable middle class (at risk of sliding down the poverty ladder), 21 percent represent the stable middle class and only 3 percent are classified as elite. Depending on the socioeconomic class of a person, not only will their needs and hence the life insurance products purchased differ, but these groups also tend to have different likelihoods for mortality and morbidity.

The Impact of Covid-19

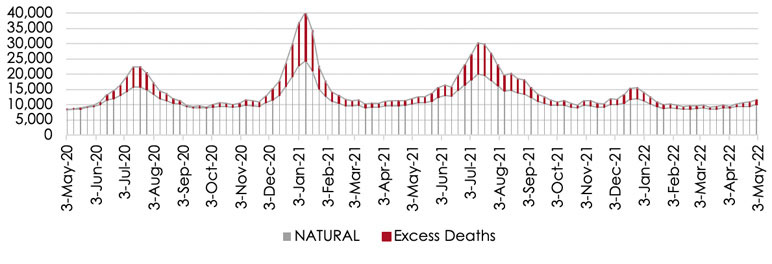

The impact of Covid-19 in South Africa in terms of excess deaths was substantial, when considering the reported excess deaths as published by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC).[4] Please note that in this article we will not further consider whether all excess deaths can be directly attributed to Covid-19, however, as per the article “Correlation of Excess Natural Deaths with Other Measures of the Covid-19 Pandemic in South Africa,”[5] it is estimated that 85 percent to 95 percent of excess natural deaths are attributable to Covid-19.

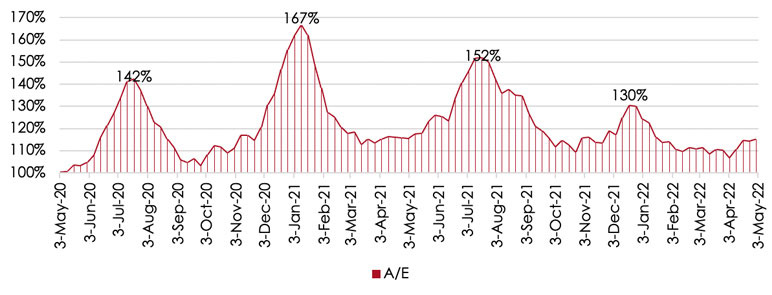

Based on the SAMRC excess deaths, taking the expected plus excess deaths as Actual and expected natural deaths as per their methodology as Expected, we observe an Actual versus Expected (AvE) ratio of 116 percent in 2020, a ratio of 131 percent in 2021, and a ratio of 113 percent in 2022 up to May 1. When we look at the AvE for each wave, we can see that the 2nd wave (predominantly Beta variant) and the 3rd wave (predominantly Delta variant), had the most severe impact on the general population (see figure 2 and figure 3)

Figure 2

Expected and Excess Deaths

Figure 3

Excess Deaths

Taking AvE of over or under 120 percent as an indication for the beginning and end of a wave respectively, we can consider the experience during as well as in between waves. For the Beta wave the average AvE was approximately 146 percent, whereas for Delta the average was 132 percent. The AvE between Covid-19 waves was still relatively high in 2021 at 116 percent.

It is important to note that when both the Beta and Delta variants spread in South Africa, the vaccine immunity was close to zero, and arguably the natural immunity was still low. As such, the population was vulnerable when these waves hit, and this is generally thought to be one of the main reasons for the high excess deaths as a result of Covid-19 in South Africa compared to other countries.

The AvE for life insurers over 2020 and 2021 turned out to be much higher than the excess death AvE based on the SAMRC data for the national population, with AvE’s on an expected versus actual claims basis being up to 300 percent for some. There are various theories with regards to the reasons for this, some of which I will unpack below.

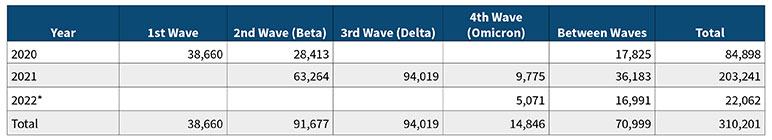

Firstly, on a calendar year basis, 2021 was impacted by the two most significant waves: the majority of excess deaths for Beta (69 percent) and all death claims for Delta came through in 2021. Furthermore, 51 percent of all excess deaths between waves were recorded in 2021. In fact, on aggregate, 66 percent of all Covid-19 related deaths to date can be attributed to 2021. (see table 1)

Table 1

Excess Deaths in South Africa

*only up to May 1, 2022

As such, it is not surprising that when considering death claims on a calendar year basis, 2021 was a particularly adverse year for South African life insurers. Those insurers that have December year-ends would have had significantly higher death claims in 2021, whereas those with June year-ends would have been able to dilute the impact across June 2021 and June 2022 results.

Secondly, in South Africa the insured population is older on average than the national population, with an average age of 27.6 years.[6] As Covid-19 case fatality rates were higher for older ages, it is to be expected that the average increase in mortality due to Covid-19 for the insured population would be higher than for the general population.

Thirdly, if we consider the excess mortality based on number of deaths for the insured population and compare this to the national population, and if we adjust for the differences in the age structures of these populations, the results may be more comparable. However, it is on an expected versus actual claims paid basis, which takes into account the sum assured, that insurers saw much worse experience than on a number of claims basis. For some this was as a result of a few deaths of policyholders with extremely high sum assureds in their portfolios, but this was also as older policyholders on average tend to have higher sums assured than younger policyholders.

Lastly, the socioeconomic impact played a role in the difference in the expected mortality rates for the insured population compared to that for the general population. Let us consider this on a simplified basis. Pure risk policies tend to be targeted at higher income individuals in the population. These individuals typically have healthier lifestyles and are afforded better access to medical care, and as a result the expected mortality rates tend to be significantly lower than for the general population. However, Covid-19 led to a significant increase in the mortality rates for these individuals relative to the low expected rates. This impact is exacerbated by the fact that the sums assured for this type of policyholder can be very high. On the other hand, for products that cater for lower income individuals, the difference between their expected mortality rates and the mortality rates of the general population is typically not as big as for the higher income individuals. Furthermore, the sums assured for these products are not as high. A large proportion of these products will be funeral products, where the maximum sum assured is prescribed by regulation. As such, the impact on AvE on a claims basis would be more heavily skewed to those with higher sums assured, where we would have seen a very high relative increase in the mortality rates during Covid-19 waves compared to the mortality rates expected under normal circumstances.

Please note that in addition to the above, there would inevitably be some others of which I am not yet aware, including other reasons specific to particular portfolios.

South African Life Insurance Industry Response during Covid-19

One of the responses that South African life insurers had to Covid-19 is to establish short-term Covid-19 provisions for the next 12–24 months, in order to manage profit emergence in future periods. This was possible due to the current treatment of IFRS reserves, whereby the actuaries in South Africa have discretion with regards to establishing special reserves. These reserves have then been run-off over time as Covid-19 claims emerged, and new provisions were established for further future expected excess Covid-19 claims. There were varying views on whether these provisions should be stressed along with other Best Estimate Liabilities under the prudential regulatory solvency framework.

These provisions were generally established for mortality, lapse and retrenchment claims. It turned out that there was no need for lapse provisions, as lapse experience actually improved during Covid-19. Whereas life insurance was deemed a luxury in previous financial crises, during Covid-19 it was deemed a necessity.

As a whole, the industry remained resilient from a solvency perspective, with only a few insurers facing challenges in terms of their solvency position during Covid-19. However, it was a massive earnings event for the industry, with dividends being reduced from R12.3bn in 2019 to R1.0bn in 2021.[7]

South African Life Insurance Industry Response Looking Forward

The industry is currently still considering whether we expect a pandemic with a similar impact to Covid-19 to occur more often going forward, e.g., once in every 10 or 20 years, or do we consider it to be an extreme event that will not occur regularly, e.g., once in every 50 to 200 years. The answer to this question very much determines the approach that an insurer would take to managing this risk. If the view is that it will happen frequently, the approach might be to include a pandemic loading into Best Estimate assumptions for pricing and reserving. If the view is that it will not happen frequently, insurers might decide to transfer this risk to, for example, a reinsurer, or to ensure the regulatory and/or economic capital held in respect of pandemic risk is adequate and that the cost of this additional capital is reflected in the pricing. We observe that some insurers have started adding pandemic-loadings to premium rates, to some extent driven by reinsurers in the market.

This discussion has led to other questions. If a pandemic is expected to emerge only once every 10 or 20 years and the approach is taken to increase Best Estimate assumptions from a reserving and pricing perspective, how would we deal with these loadings under IFRS17 and how do we treat the emergence of mortality profits on an annual basis for years where a pandemic did not occur? And if we do load premiums on long-term products for future pandemics, and we do not see another pandemic similar to Covid-19 in the next 50 years, how do we ensure we still treat customers fairly?

Further to the above, as an actuarial profession we are looking at the Life CAT solvency capital requirement calibration as per the Prudential Authority’s financial soundness requirements, and we are considering whether, given what we have seen with Covid-19, the calibration is still appropriate.

What Can Others Learn From What We Have Seen in South Africa?

As mentioned for the majority of life insurers in South Africa, Covid-19 was not a solvency event, but definitely an earnings event and for some also a liquidity event. As such, we will have to consider pandemic scenarios in our ORSA’s in more detail in the future. We cannot only consider their direct impacts on mortality and morbidity, but we need to also consider their secondary impacts, e.g., operational impacts and reduction in new business volumes due to lockdowns impacting distribution channels. We should also consider the impact of these not only on solvency positions, but also on earnings and liquidity.

For populations with very different socioeconomic groups, we need to consider the potentially skewed impact on a claims basis when considering pandemics and the impact thereof. Furthermore, a relative increase in very low mortality rates will not always be reflective of the impact of a pandemic on an insurance portfolio. Consideration should be given to the absolute expected mortality rates during a pandemic.

Lastly, while we are expected to predict the future in our long-term life cashflow projections, we have certainly been humbled by this pandemic, and reminded that we will never get it exactly right. It is therefore important to manage the expectations around inherent uncertainty, which remains as we hope we are seeing the end of Covid-19 as a pandemic. As Kelefilwe Kungwane said during a recent actuarial industry panel discussion, “even when facing uncertainty in the future, we have to take a stance based on the information we have today.” And the good news is, we have learned a lot from this pandemic, so we can only be better prepared for the next.

The author would like to acknowledge Jaco Louw and Ernst Landsberg for their involvement in writing this article.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Idelia Hoberg, FIA, CERA, is a life actuary based in Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa. She can be reached at ideliahoberg@gmail.com.