The Opportunity of a Lifetime

By Doug Robbins

Product Matters!, February 2023

The events in this tale happened somewhere in the multiverse, on a parallel planet Earth, but they could conceivably happen here. They offer what could be a valuable lesson in precisely what we glean from a pair of pricing techniques, which modern actuaries use for complex insurance liabilities. The hero of our story is a young actuary called Padme, so named by her parents, who were big fans of the “Star Wars” queen of the same name.

An Exotic Parlay

It is well known that as an uber-popular event, you can place a bet on a plethora of different events related to the Super Bowl. Far from being limited to things that impact the winner or loser of the game, Padme’s universe has seen bets on things like game-time temperature, length of half-time show, and final game attendance. There has certainly been an active market on the coin-toss outcome: an even-money bet on heads vs. tails.

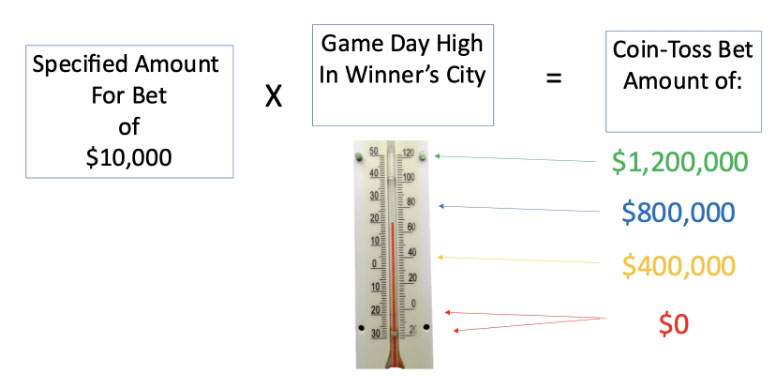

Padme has for the past few years noticed an exotic parlay available the day after each Super Bowl, applied to the Super Bowl that will occur one year later. This parlay allows the participant to specify a factor applied to game-day high temperature (Fahrenheit) in the winning team’s hometown, as published by The Weather Channel. This amount is the amount that will be won or lost on the heads/tails bet on the coin toss. For instance, if a notional amount of $10,000 is specified for the bet, the total won or lost on the heads/tails bet could easily be $800,000 if Miami (which could certainly hit 80 degrees that day) were next-year’s winner, or could be $100,000 or less if the winner happens to be Minnesota. (Thinking about that locale’s winters, we’d better stipulate that our win/loss amount is floored at $0—we want no negative bets.)

Here is a graphic display of sorts that lays out how the bet works:

This bet has become such a sensation that an online, bookie-free market has developed. Participants, by mutual cooperation, are thus able to obtain their preferred level of “thrill” with no expected “house cut.” They receive “true odds,” with a long-term expectation of breaking even. This has grown into such a huge market as a result, that an options paradigm has developed around the bet, with puts and calls bought and sold “at the money.” (Although in this case it’s interchangeable, let’s define a put as the option that covers a heads bettor’s loss if the actual result is tails but otherwise pays nothing. Thus, the call would be the opposite end.)

Padme has noticed that those options’ costs have varied year-to-year as a percent of the amount specified in the bet. Some years, for example, a put or call on a $10,000 specified bet might cost $200,000, and other years $250,000 or $175,000. Padme didn’t know for sure why this proportional cost as a percent of amount bet varied year-to-year, but she chalked it up (correctly, as it turned out) to the options market pricing risk differently depending on what else was going on: think climate risk, and/or an assessment of the next-year’s NFL teams, by latitude.

Padme did spot the fact that, for any given year, put options for a given notional amount always cost the same amount as the call options for the same notional. She assumed that that was because the gain or loss for a given bet was the same. (She also understood intuitively that since there isn’t really a long or short side to this bet—i.e., there isn’t a valuable notional amount transferred from one party to the other during the year—the available risk-free interest rate for this bet has nothing really to be applied to. It’s moot, as if it were 0 percent.)

Padme was a gamer, and had always wanted to play in this market, but as a young actuary she could never justify risking even a minimal specified amount of say $1,000, given the conceivable $80,000+ loss. She had considered making a heads bet, that being her go-to on coin flips, and buying the put option that would protect her against a tails outcome. But even the typical put premium of $20,000 or so felt a little rich, so she had always passed.

The Opportunity of a Lifetime

Then one year, on a major anniversary of the advent of the “Star Wars” saga, it was deemed a year ahead of time that the coin flip would use a special commemorative coin. On that coin, the heroes of the “Star Wars” series would be featured on the heads side, and the villains on tails.

The unforeseen consequence of that decision was that the normal betting market failed to gel, because an outsized number of bettors wanted to back the villains and choose tails. Not wanting their special coin to be known for ruining this venerable gambling tradition, the Disney Company offered a 5 percent bonus for anyone choosing heads on their bet, to be paid only if heads did turn out to be the correct call. The market then quickly stabilized, with an equal amount wagered on both sides of the bet, and with put and call options for sale as before.

Padme was obviously thrilled by all of this, as the tribute to her namesake (among others) just made the chance to bet her preferred side—heads—even sweeter. It was the opportunity of a lifetime! She went online, realizing this would give her an opportunity to place a heads bet with a specified amount just a bit over $952 (~$1,000 / 105 percent), and still stand to win the amount that a $1,000 specification would normally return. She still didn’t love the risk involved though, so she set out to buy a put option, assuming that since everyone knew Disney was paying a premium on the heads bet, the put would be cheaper than the call this year.

She was at first dumfounded to find out that for her $952 Notional Bet, the put and call options both cost $19,000. How could this be, given that everyone in the market knew that a bet on heads had a positive expected return, but tails still had the expectation of breaking even?

That Darned Put-Call Parity

Padme cracked her old actuarial exam texts and quickly spotted the reason for the phenomenon: put-call parity, which is a necessary condition of any deep, transparent, liquid options market. The key question she finally asked herself was: what if, due to the Disney premium on heads, put options were to cost less than calls? Let’s say calls were 21x Notional, with put Options costing 19x. Remembering that this is a market where anyone can bet either way on the coin toss, as well as buy or sell a call or put, she saw that in that case, someone could do something like this (there are other opportunities, but we’ll choose one):

- Make a bet with a huge specified amount, say $500,000, on heads.

- Sell a call option and buy a put, both reflecting that specified amount.

- By doing those things, lock in a gain of 2x notional no matter what happens: in this case, a profit of $1 million. (This is what’s known as taking advantage of “arbitrage.”)

It is simple to illustrate: the $1 million gain is just the difference between the gain on the sale of the put for 21x notional (or $10.5 million), and the purchase of the call for 19x notional (or $9.5 million). Once that position is set, and subject to the temperature variable, the coin toss produces one of only two possible outcomes (see Table 1):

Table 1:

Possible Outcomes

| Coin Toss Outcome |

Bet Outcome |

Put Outcome |

Call Outcome |

|

Heads |

+$Temp * $500k *1.05 |

$0 |

-$Temp * $500k *1.05 |

|

Tails |

-$Temp * $500k |

+$Temp * $500k |

$0 |

In other words, after pocketing the $1 million, this hypothetical bettor can lock in a complete wash, no matter the result of the temperature or coin toss.

Padme realized that, implicitly, this thing we call “the market” of heads and tails bettors has set a price of $0 (there’s no charge assessed, to play) to enter this coin-flip bet in either direction, regardless of the impact of the Disney premium. The market sets prices on positions every day—for various relatively simple arrangements like this one, and also for more complex things like stock prices and bond coupon rates, just to name a few. The market might assign such a price in a way that allocates an expected premium to one side or the other, and it can do so for any reason it wants, or for no reason at all.

But wherever the market ends up setting that initial price, it becomes the “at-the-money” point for put and call options; and if the risk-free rate is zero (or moot, as in our case), puts and calls struck at-the-money must have equivalent costs. Any other result would allow risk-free profit greater than the risk-free rate (again, aka “arbitrage”). And a deep, transparent, liquid market should never do that.

Actuarial Pricing with Risk-Neutral vs Real-World Scenarios

Padme thought some more about this, in a way related to a pair of paradigms her unit had used to price complex liabilities recently: the real-world paradigm and the risk-neutral one. Her boss had told her that real-world scenarios use historical averages to predict future asset returns, but that risk-neutral ones are “market consistent,” in that they reflect current asset prices. She now realized that although both of those statements are true to a point, they could be misleading to new practitioners, if not thought out and carefully explained.

For the real-world set, the name implies that we have information about what the future “real world” is like. Well… we may, or may not, based on historical averages. Surely all investors out there are familiar with the adage that “past results do not predict future returns.” A lot about any given market can change on a dime, creating a distinct new “real world.”

However, Padme had now discovered a way in which calling risk-neutral scenarios “market consistent” might be misleading. And to her, this seemed far more interesting!

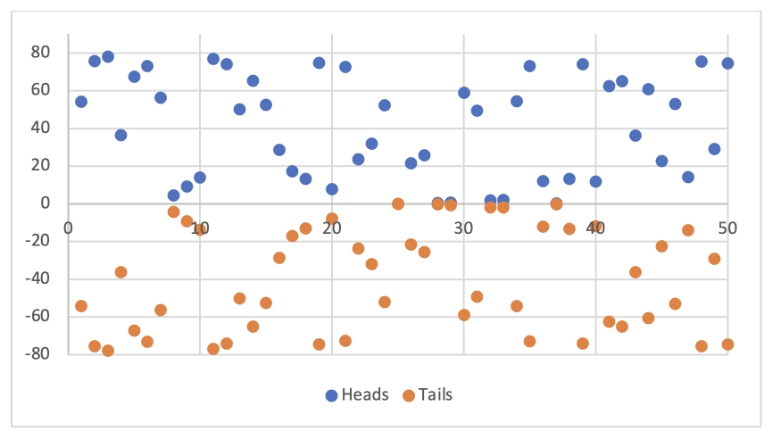

In all previous years of the Super Bowl coin-flip market, valid sets of real-world and risk-neutral scenarios could have arguably been identical. In other words, however the real-world set ended up being constructed, the risk-neutral set might easily be exactly the same, as long as the average win or loss, based on temperature, matched up with the option costs available that year. E.g., if the option costs were 20x the specified amount, the average scenario high temperature would need to be 40 degrees—not unreasonable for early February in America. An example set of 100 total scenarios that could be called real-world AND risk-neutral can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Outcomes of 100 (Weather X Coin) Scenarios, Any Year without Disney Premium

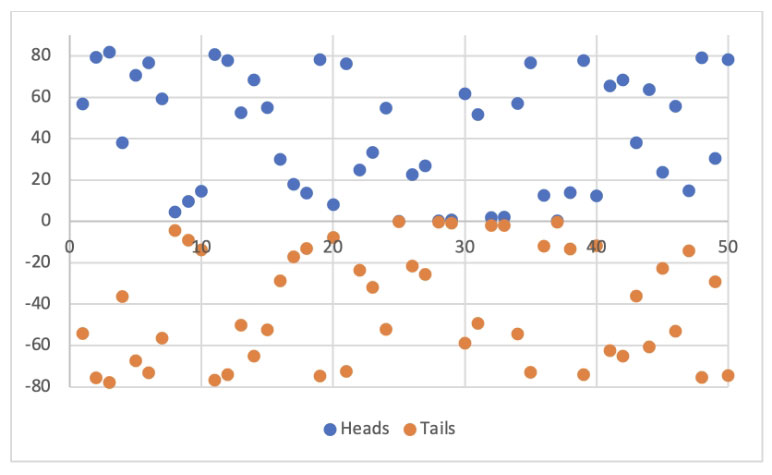

The Disney premium had now changed things in the real world. For this year only (assuming Padme’s preferred heads bet), the positive scenarios should all return 105 percent of the high temperature within that scenario, while the negative ones could be unchanged (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2

Outcomes of 100 (Weather X Coin) Scenarios, the Year with Disney Premium

All of the blue dots in the real-world scenario set have moved upward just a bit, to reflect (and this is key) what the actual pool outcome would be if that scenario were to occur.

But the risk-neutral set would not look like that at all; in fact, it might be exactly as it was before, producing equivalent put and call costs of about 20x the specification. Within this context, the Disney premium would simply fail to exist, because including it would overvalue the call options, compared to their market price.

Now, when used as intended, the risk-neutral scenario set is truly “market-consistent”: one can use it to reproduce the market’s prices for puts and calls, along with other derivatives. But there is also an important way that this set is “market-inconsistent”: the market has set an entry price into the bet at $0, knowing the potential results of the bet, including the Disney premium—a premium that any projections using the risk-neutral scenarios will simply ignore.

Again, no one can tell the market it is wrong—the correct market price for any asset is whatever the market says it is. But it is transparent and obvious that the Disney premium exists and will affect the heads outcomes. Thus, a forward projection of betting outcomes using the risk-neutral set is on its face inconsistent with reality.

The bottom line is that the average return on an asset valued using the risk-neutral set will always be the risk-free rate (in our case, 0 percent), but this is not based on any kind of prediction whatsoever (unlike in the real-world paradigm). It is simply a requirement based on the math of options pricing and put-call parity.

Padme boiled all of that down to the following three thoughts:

- Risk-neutral or “market-consistent” scenarios, if constructed perfectly, will reproduce market prices of derivatives.

- Real-world scenarios, if the real world turns out to be in line with them, can project for us a set of future asset prices that allows us to evaluate our expected future position.

- Crucially: if we take a market position, but then hedge away all of the risk in that position, we can and should expect to make exactly the risk-free rate.

However, Padme had also heard someone say the following: “The risk-neutral paradigm demonstrates that in a market-consistent world, even risky assets can only be expected to return the risk-free rate.” Padme now saw that this statement is wrong, at least in our example, so possibly in all examples.

Padme’s Conclusions

Thinking about this further, Padme drew some conclusions that she intended to apply in future pricing work.

In many markets where actuaries discuss these two paradigms, assets held in the real world are assumed to be priced to contain a risk premium, but that premium isn’t tangible. You can’t grab ahold of it directly—you only project future results based on a history-based, but possibly stale, viewpoint. This is true even for corporate bonds, where the risk premium is somewhat explicit, but not guaranteed to pan out. (Far from it, as the holder can lose money even if they attempt to hold their bond to maturity, unlike with “closer to risk-free” treasuries.)

And since a hedging program and the risk-neutral paradigm convert future results into de-risked values that seem more tangible and guaranteed, they are often discussed as though they are in a sense more “real” than the real world.

Because this tangible, guaranteed paradigm produces scenarios with expected returns for all asset classes equal to the risk-free rate, one might easily take this to support the theory above: that risk-neutral pricing implies that all one can expect to make, even on unhedged risky assets, is the risk-free rate. Padme now spotted the flaw in this reasoning, based on a constraint that all risk-neutral scenarios must bow to.

Even for an asset with a real and tangible premium, which everyone in the market is aware of, risk-neutral scenarios will still contain average returns equal to the risk-free rate.

Everyone in this special Super Bowl pool is fully aware that the expected return on tails is 0 percent, but the expected return on heads is a positive 2.5 percent. The relevant market has decided to price the “at-the-money” point of this asset at $0 anyway, and the market price is the market price, which is the market price. People in all markets have preferences and theories (e.g., “The Sith are the real heroes in the story, and I can’t stomach betting the other way.”), and they impact asset prices every day.

The real-world scenarios correctly model the heads/tails payoff distribution, and they give us an expected gain on a heads (or tails) bet, showing that heads is better. The risk-neutral ones correctly reproduce the put and call prices that are out there.

But if anyone were to claim that the risk-neutral paradigm implies that the true expected return on heads is 0 percent? This would not be some alternative pricing theory—it would be nonsense on stilts.

You can certainly get back to an expected 0 percent return by hedging away all the risk. But in this game Padme wants to play, if she lays an unhedged heads bet, she of course might lose; however, if she wins, she will win more than she would lose. Thus, she has a positive expected outcome—it’s simply inarguable.

And if the risk-neutral paradigm, with its constraints, can’t help but get this simple example “wrong,” it really can’t have anything to tell us about expected outcomes of unhedged risky market positions in general. If we want to estimate those, all we can do is try to come up with a projection of the real world, and hope that we’re doing so reasonably.

Padme took the heads bet and crossed her fingers. And then she went back to work, determined to take these conclusions into account in all of her actuarial endeavors!

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Doug Robbins FSA, MAAA, is the CEO of Early Bird Enterprises LLC. He can be reached at doug@myactuary.com.