Modeling the Unwinding—Where Are We Now?

By Colby Schaeffer

Health Watch, May 2024

The great unwinding in Medicaid has been an ongoing event over the last year, during which Medicaid beneficiaries have lost coverage following three years in which hardly anyone did. Why? Much of it is due to catch-up in states that are now able to act upon eligibility redeterminations. Four years ago, the COVID-19 pandemic led to Congress passing the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. This boosted federal government funding of Medicaid with a 6.2% increase to the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP), the portion of Medicaid expenditures that the federal government pays. The passage of this legislation recognized that Medicaid enrollment would increase significantly due to sudden job losses and economic uncertainty at the advent of the pandemic. Maintenance of Effort (MOE) requirements were put in place for this additional funding, which would last throughout the official COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE). Medicaid beneficiaries would be allowed continuous coverage, even if they were no longer eligible. States could still choose to continue eligibility verifications, but coverage was lost only if individuals rejected it, passed away or moved out of state. Ultimately, total Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollment increased by 22.6 million beneficiaries from March 2020 to March 2023, a total change of 31.6%. On April 1, 2023, the unwinding of these continuous coverage provisions started in several states, with most other states starting their first terminations by the end of June 2023.

As of March 2024, the unwinding was almost complete, yet a lot of downstream effects are expected to occur. It is critical for the overall health insurance system to ensure that people maintain coverage and continuity of care. State budgets are significantly impacted as the 6.2% increase in FMAP was phased out by 2024. The per capita funding of Medicaid beneficiaries and average cost of those enrollees are unequivocally tied to the unwinding as well. The financial questions of total cost, total enrollment and average cost involve actuaries.

While the unwinding broadly impacts Medicaid, as well CHIP, some beneficiaries are affected more than others. Eligibility groups such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Affordable Care Act (ACA) Expansion tend to be impacted the most since they may go on and off the program frequently (what is typically called “churn” in Medicaid). With churn not happening for three years during the pandemic, enrollment was much higher than normally expected. Many beneficiaries may already have employer-sponsored health care or other coverage. As people drop off, this could impact other lines of business, especially the Healthcare Marketplace exchange plans which are very much the backstop for Medicaid.

Modeling the Unwinding

The Society of Actuaries (SOA) sponsored the development of a model and research paper to help actuaries and those working within or adjacent to Medicaid finance tackle the question of effects of the unwinding.

The model measures two major outputs:

- Projected changes in enrollment for up to nine different populations (or cohorts or groupings)

- Average changes in acuity as that enrollment changes, as driven by other assumptions and inputs within the model

Acuity is essentially the average cost of a population with all other things being equal. For instance, benefit changes, fee schedules and reimbursement, trends, regulatory impacts and population mix can all change a population’s cost over time, but if the behavior of that population suddenly changes, then an acuity adjustment may be needed. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has a capitation rate development guide that documents this as “an adjustment applied to the total payments across all managed care plans to account for significant uncertainty about the health status or risk of a population is considered an acuity adjustment.” The model controls how acuity changes over the duration of enrollment of the average covered individual in a population.

Duration matters a lot more with Medicaid than with other payers, likely due to the nature of churn and beneficiaries coming on and off the program. With a portion of churning beneficiaries returning to the program for various medical reasons, acuity can vary significantly with duration of enrollment. Some Medicaid actuaries will review duration on a routine basis to evaluate whether durational curves are changing with respect to a medical loss ratio, which by proxy can be used as an average cost measure, provided all other things are equal at a given time.

Primary sources used in the research included CMS monthly Medicaid and CHIP enrollment from January 2019 through January 2023, as well as the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS) Monthly Enrollment by Major Eligibility Group (MEG), also from CMS. Most important with the model, users can override the CMS data with their own enrollment numbers. This is especially helpful when someone is not looking at statewide or national membership counts; for example, a health plan can assess regional and rate cell impacts as it goes through the unwinding and even a subsequent procurement or expansion.

Base assumptions in the research paper came from a variety of sources. As the model does not necessarily predict how many lose coverage, which is an assumption input in the model, it was critical to collect multiple sources for such assumptions. The loss of coverage during the unwinding has been a heavily covered topic, and we relied on a combination of other forecasts, including the Kaiser Family Foundation, the Urban Institute and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, to determine the right estimate. A MACPAC study on rates of churn and continuous coverage under Medicaid and CHIP found that churn was 30–50% for children and young adults.[1] Steady state disenrollment patterns before and during the pandemic were estimated through reliance on a Stanford University study. For how acuity would vary by duration of enrollment, the research team used some publicly available data from states that showed how costs were being diluted and acuity lessened with the increasing enrollment. Data predating the PHE from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) was analyzed to get a sense of how acuity changes by duration of enrollment. AHRQ has a synthetic data set that can be used for Medicaid, Medicare and commercial populations. This data set summarizes data from claim samples, so the high and low outliers were removed from the data to get a better sense of how acuity truly varied.

Report Findings—Enrollment

Our research paper concluded that net enrollment change would be 9.0 to 18.0 million people losing coverage, with a midpoint of 12.8 million. It was a wide range that was controllable within the model. Earlier in the unwinding, there were varied opinions about how many people would lose coverage.

As of the beginning of May 2024, 21.0 million beneficiaries had lost coverage, and the unwinding was at least 71% finished.[2] While this could easily suggest that over 25 million will lose coverage, the expectation is that a number of individuals who have lost coverage will rejoin Medicaid (and CHIP).

This churn is a controllable input in the SOA model and was accounted for in the 12.8 million midpoint estimate. For example, if the unwinding’s national impact resulted in a gross disenrollment of 21 million people and churn was 40%, that equals 8.4 million beneficiaries returning to coverage, which is a 12.6 million net disenrollment. The key takeaway is that a full measurement will not be possible until another year beyond the unwinding.

Report Findings—Acuity

In general, acuity is expected to return to pre-PHE levels. That is a central thesis of the research paper and a controllable element within the model. To return to that level, the system has to even itself out in terms of utilization patterns, churn and regular enrollment. This means that we have to look at given churn patterns least a year past the unwinding. This would take us to late 2025. Furthermore, when it comes to Medicaid rate setting, the data used are often from two years before the rating period, so the changing acuity patterns could have rate impacts all the way into the 2027 rates.

Medicaid capitation rating periods can vary. Most are by calendar year or state fiscal year, which usually has a July 1 effective date. Some other states, such as Arizona, have a rating period that starts October 1. Using publicly available rate certification and fiscal note information from some states, a similar pattern has developed in regard to acuity adjustments for the unwinding in capitation rates with respect to similar Medicaid populations such as TANF Children, TANF Adults and ACA Expansion Adults.

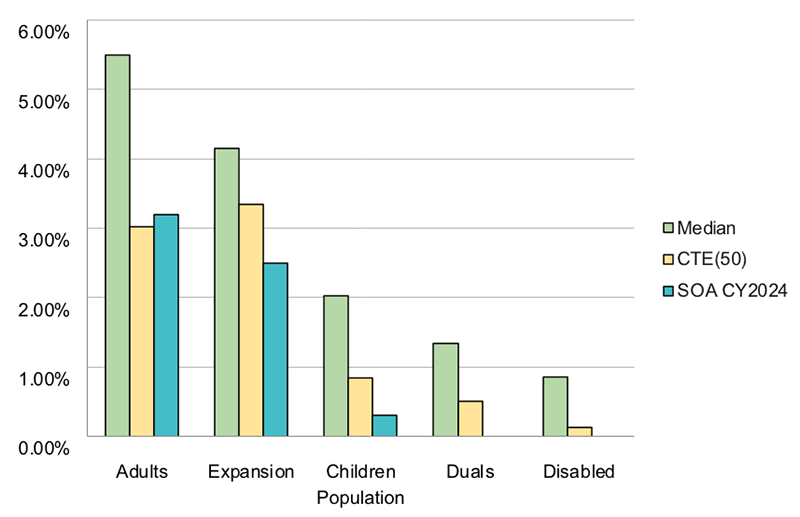

Some of the limited capitation rate information available is for periods beginning in 2023. Capitation rate impacts will vary by state depending on the state’s unwinding approach, covered populations in the managed care program and, most importantly, the timing of the base data being adjusted with respect to the rating period. These observations do appear to align themselves with the results modeled in the SOA research paper, although as Figure 1 shows, the modeled results are on the lower end of the observations, being comparable to the conditional tail expectation that is below the 50th percentile (average of bottom half of distribution).

Figure 1

Comparing Observed Acuity Adjustments to the SOA Model

Acuity adjustments for the unwinding should be expected for rating periods effective July 1, 2024, as well as periods beginning in 2025. As the base data used for capitation rates start to reflect post-unwinding periods (2024 onward), acuity adjustments may not be needed. However, as noted, churn patterns could take some time to settle.

Additional Use Cases

There are other ways to leverage the SOA model beyond the unwinding and its effect on the Medicaid rate setting. The SOA model is very flexible and can be tailored to any acuity/cost variation by duration for a non-Medicaid population. A state or health plan can model future shifts in enrollment or changes in expected acuity. The custom population groupings can also be used to map movement between Medicaid and Marketplace plans.

Conclusion

While the unwinding is almost finished, the data used by actuaries will not fully reflect its completion until late 2024 and perhaps well into 2025, when churn patterns should return to normal. It’s an event that, although long anticipated by those working in Medicaid, sets itself as an example to be used for other major changes in eligibility or coverage. Actuaries need to consider the varying ways that the risk profiles of enrollees are impacted and need to work with their stakeholders to have a rich exchange of information regarding these possible drivers.

For those interested in more detailed information, the following link will take them to the research report, Excel model and model user’s guide: https://www.soa.org/resources/research-reports/2023/unwinding-phe-state-medicaid/.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Colby Schaeffer, ASA, MAAA, is a founding partner of Inline Actuarial Group. Colby can be reached at colby@inclineag.com.

Endnote

[1] Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “An Updated Look at Rates of Churn and

Continuous Coverage in Medicaid and CHIP,” MACPAC, Oct. 2021, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/An-Updated-Look-at-Rates-of-Churn-and-Continuous-Coverage-in-Medicaid-and-CHIP.pdf.

[2]KFF, “Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker,” KFF, Apr. 4, 2024, https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-enrollment-and-unwinding-tracker-overview/.