Bridging the GAAP: IFRS 17 and LDTI Differences Explored

By Gregory MacKenzie, Su Su and Tina Guo

The Finanical Reporter, July 2022

Highly anticipated accounting changes for life insurers are around the corner with International Financial Reporting Standard 17 (IFRS 17) and Accounting Standards Update 2018-12, commonly referred to as long-duration targeted improvements (LDTI), both effective on Jan. 1, 2023, for public companies (with implementation for the majority of non-public companies soon to follow by 2025).

IFRS 17 and LDTI are the biggest accounting changes for life insurers in decades. When reviewing the financials of multi-national insurers, users will need to translate between the two accounting models or, at minimum, understand both.

This article discusses key considerations and differences in measurement requirements between IFRS 17 and LDTI, leveraging a term insurance example to illustrate potential impacts on liabilities and, ultimately, earnings emergence.

Context for Example

A 20-year level premium term product with yearly renewable post-level premium underlies the example used throughout this article to provide insight on interpreting and comparing financial statements under the two standards. Liability impacts and earnings emergence patterns are compared and contrasted across multiple scenarios highlighting key differences. Assumptions under the baseline scenario are:

- All contracts issued within the same year,

- no cash surrender value,

- 100 percent shock lapse at end of level premium period,

- investment income based on US statutory distributable earnings, and

- IFRS 17:

- All expenses are directly attributable and included in the liability for remaining coverage (LRC).

- Contractual service margin (CSM) is amortized based on face amount.

- Risk adjustment is 10 percent of best estimate claims.

- Liability cash flows discounted and contractual service margin accreted using discount rates constructed based on reference portfolio.

- LDTI:

- All expenses are non-claim related and excluded from the liability for future policyholder benefits (LFPB).

- Upfront commissions in excess of renewal commissions in policy year one are capitalized via a deferred acquisition cost (DAC) asset; all other expenses are expensed when incurred.

- DAC is amortized based on face amount.

- Liability cash flows discounted using upper medium grade (UMG) fixed income rates.

Accounting Methodology: IFRS 17 Versus LDTI

The foundational differences between IFRS 17 and LDTI, described below for traditional life insurance products, are important to understand before diving into expected earnings emergence.

IFRS 17

The IFRS 17 LRC for the illustrative term product comprises; 1) best estimate liability (BEL), 2) risk adjustment (RA), and 3) CSM.

The BEL is calculated as present value of benefits and directly attributable expenses less present value of gross premiums using best estimate assumptions (commonly referred to as a gross premium reserve in other valuation contexts). Cash flows are discounted using rates derived based on a reference portfolio intended to replicate the liability cash flows.

The RA represents compensation the insurance company requires for the uncertainty in the insurance cash flows. In practice, several methods are used to determine the RA (e.g., multiplicative factor applied to assumptions, cost of capital approach, other statistical methods).

The BEL plus the RA is referred to as the fulfillment cash flows (FCF).

If FCF is negative at inception, a CSM equal to its absolute value is established to avoid recognizing unearned profits at inception; the CSM is then amortized into profit over the life of the contract.

LDTI

The LDTI net GAAP liability for the illustrative term insurance product comprises, 1) LFPB, and 2) DAC.

The LFPB is calculated as present value of benefits and claims-related expenses less present value of net premiums using best estimate assumptions (commonly referred to as a net premium reserve). Cash flows are discounted using UMG discount rates.

Acquisition expenses are capitalized when incurred and a DAC asset is posted on the balance sheet. The DAC asset is amortized without interest over the life of the policy over an in-force metric.

Baseline Earnings Emergence

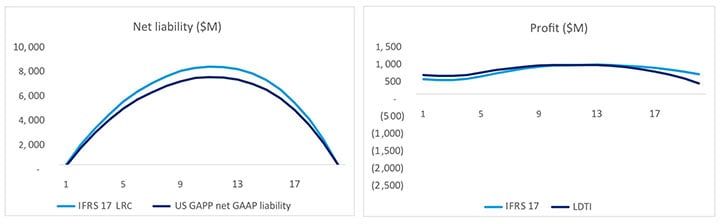

Using baseline assumptions for the term example and projecting a profitable group of business, the net liability and profit emergence for IFRS 17 and LDTI are very similar. Both accounting models set up a reserve for future policyholder benefits and recognize upfront costs over the life of the policy, leading to largely uniform profit emergence.

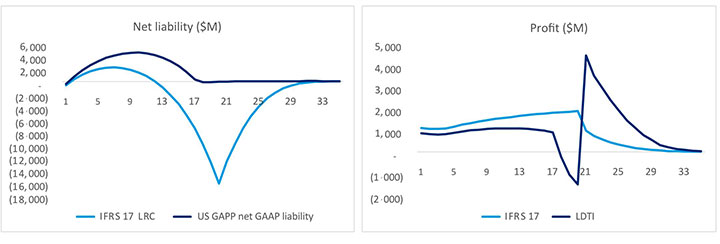

As demonstrated in Exhibit 1, the net liability run-off and corresponding profit emergence between the two standards is largely aligned, which is intuitive given the overarching goal of both accounting models is to recognize profit as insurance services are rendered.

Exhibit 1

Liability and Earnings Emergence for a Profitable Block of 20-year Term Policies

Under IFRS 17, profit is attributable to the release of the RA and CSM as well as investment income earned. Under LDTI, profit from insurance cash flows is a function of premiums (given the net premium reserve approach) and the amortization of DAC. Similar to IFRS 17, investment income and overhead expenses also contribute.

While earnings emergence is very similar between the two models in this simplified example, in practice the liability and earnings emergence between the two models will likely be different as discussed below.

Measurement for Unprofitable Contracts Under IFRS 17 and LDTI

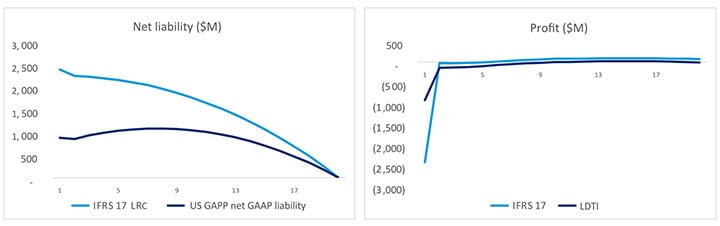

For unprofitable business, earnings emergence diverges between the two accounting models.

As is illustrated in Exhibit 2, for an unprofitable block, all else equal, the initial reserve increase will be more punitive under IFRS 17, due to the inclusion of the RA as well as (presumably) additional expenses in the liability calculation under IFRS 17. The higher initial reserve increase for IFRS 17 leads to a larger negative impact to income upfront, with future profits slightly higher under IFRS 17 as the additional liability is released over time.

Exhibit 2

Liability and Earnings Emergence for an Unprofitable Block of 20-year Term Policies

Level of Aggregation

A key difference between the two accounting models is the level of aggregation at which calculations are to be performed.

Under both IFRS 17 and LDTI, contracts are grouped (or cohorted) with like contracts and business that is managed together. For example, a term insurance contract should not be grouped with a deferred annuity contract for the purposes of measurement. Both standards also do not allow the grouping of contracts issued more than one year apart.

Under IFRS 17, groups are required to be further divided based on the potential to become onerous (i.e., unprofitable). Three groups are defined:

- Contracts that are onerous at initial recognition,

- contracts that at initial recognition have no significant possibility of becoming onerous in the future, and

- all remaining contracts.

Under LDTI, like contracts are to be grouped together, but the groupings are not required to be split based on onerousness or likelihood to become onerous. Grouping based on onerousness could have a significant impact on financials.

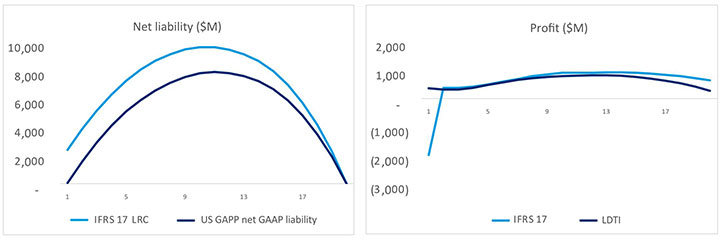

Continuing with the illustrations presented above and combining the two blocks, results look very different if the two blocks are grouped into a single cohort under LDTI and split under IFRS 17 due to the onerousness requirement, as demonstrated in Exhibit 3.

Exhibit 3

Liability and Earnings Emergence for Combined Block of 20-year Term Policies

Under LDTI, the two blocks can be combined into a single cohort, and the profitable block “subsidizes” the unprofitable block resulting in a net premium ratio below 100 percent, with no requirement to post a deficiency reserve. Under IFRS 17, the blocks are split for measurement which leads to a liability being posted at inception equivalent to what was shown in Exhibit 2. The IFRS 17 requirement to split onerous contracts from other contracts is more punitive to earnings.

Incorporating Cash Flows in the Post-level Premium Period

Reflecting cash flows in the post-level premium period also highlights differences in accounting treatment between IFRS 17 and LDTI.

Losses Expected in the Post-level Premium Period

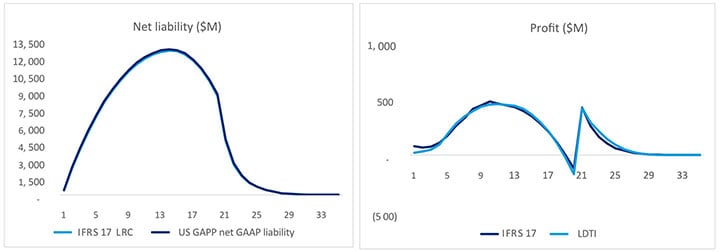

While potentially unrealistic, assuming losses in the post-level period is helpful in understanding accounting treatment differences. As demonstrated in Exhibit 4, the projected net liability and profit emergence are nearly identical under IFRS 17 and LDTI, very similar to Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 4

Liability and Earnings Emergence for a Profitable Block of 20-year Term Policies With Profits in the Level Premium Period and Losses in the Post-level Premium Period

Here, we simply extended the projection, but the overall relationship of cash flows remains the same as was observed in Exhibit 1:

- The contract remains profitable when examining the cash flows over the lifetime of the projection; and

- cash outflows exceed cash inflows in the tail, which leads to a “typical” bell-shaped reserve pattern for which portions of profits in early years are used to build up a reserve that is released in later years to cover claims under both accounting models.

Profits Expected in the Post-level Premium Period

Adjusting to assume profits in the post-level period, the requirement to floor the LFPB at zero leads to additional volatility in earnings under LDTI relative to IFRS 17.

For this scenario, the relationship between premiums and claims changes throughout the projection period. During the level premium period, premiums exceed claims in the first half of the projection, and claims exceed premiums in the second half of the projection. In the post-level premium period, the relationship flips back as premiums again exceed claims. With an unfloored reserve under IFRS 17, the reserve accumulates during the first half of the level period and releases thereafter, dipping below zero before the end of the level premium period.

Exhibit 5

Liability and Earnings Emergence for a Profitable Block of 20-year Term Policies With Profits in Both the Level Premium Period and the Post-level Premium Period

As demonstrated in Exhibit 5, under LDTI the LFPB is required to be floored at zero, leading to losses during the end of the level premium period, since no reserve releases are available to offset higher expected claims. Subsequently, a spike in profits immediately follows the end of the level premium period since premiums exceed benefits and the net premium ratio doesn’t reset (i.e., reserve remains zero and GAAP profits are a direct function of cash flows with the exception of DAC amortization).

Under IFRS 17, the LRC is not floored, leading to a smoother earnings emergence pattern as the policy crosses from the level premium period to the post-level premium period.

Financial Statement Presentation

A key focus of the changes to accounting requirements under both models was to increase transparency for users of financial statements.

Under LDTI, numerous additional disclosures have been introduced. The disclosures will help users better understand movements in results from one reporting period to the next. Companies are required to “walk” key balances from period to period breaking down movements by deviations from experience, differences in assumptions, and new business, among other items. While the new requirements under LDTI represent a significant amount of additional information provided to users, the core income statement and balance sheet are largely unchanged.

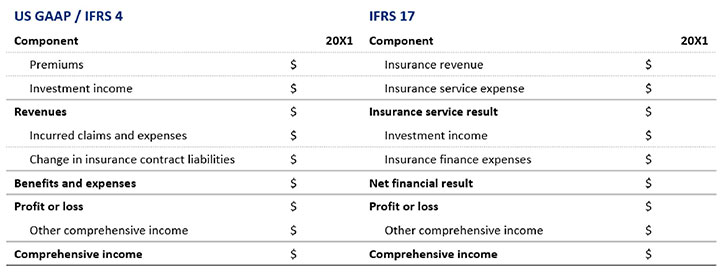

Similar additional disclosures are required under IFRS 17, but the presentation of income will be significantly different, as demonstrated in Exhibit 6. While the IFRS 4 (i.e., the IFRS immediately preceding IFRS 17) income statement looks very similar to a US GAAP Financial Accounting Standard 60 (FAS 60) income statement, the IFRS 17 income statement aims to improve transparency on sources of earnings by splitting profit and losses into two categories, amounts driven by “insurance service” results (i.e., premiums, claims, and directly attributable expenses) and amounts driven by “financial” results (i.e., investment income and non-directly attributable expenses).

Exhibit 6

US GAAP/IFRS 4 Income Statement Compared With IFRS 17

If experience emerges in line with assumptions, revenue from the insurance service result will be equal to the release of CSM (i.e., unearned profit) and release of RA (i.e., additional compensation above best estimate cash flows the insurance company requires for bearing the risk of uncertainty in cash flows).

Splitting earnings between that driven by underwriting and that driven by investments and overhead is an attractive property for users of financial statements, and one that is not necessarily achievable under US GAAP without adjustments and assumptions (e.g., users likely do not have the information necessary to split out directly attributable versus non-directly attributable expenses).

Splitting earnings into an insurance service result and a financial result works very well for traditional-type life insurance products that are priced with a healthy underwriting margin. However, the requirement to split earnings can be punitive for spread-type contracts with embedded insurance guarantees that are accounted for under IFRS 17. These contracts may appear onerous when measured using a discount rate derived consistent with IFRS 17 guidance (i.e., reflecting the characteristics of the liability and excluding credit risk premium) as opposed to using an investment earned rate. This treatment would be comparable to holding an LFPB under US GAAP for projected cash surrender value on a deferred annuity, for which the projected cash surrender value is determined using credited rates and the LFPB is discounted using (potentially much lower) UMG rates.

Conclusion

While the overarching goals of the accounting improvements are similar under both IFRS 17 and LDTI, financial statements and earnings emergence will likely look substantially different. Even with a fairly simple insurance product, numerous differences exist between the two accounting models with, arguably, the largest difference being attributed to presentation.

Users of financial statements will likely need to spend a significant amount of time understanding the improvements under both regimes, but an even greater challenge will be comparing performance for companies reporting under IFRS 17 versus companies reporting under LDTI.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the newsletter editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Gregory MacKenzie is a senior manager at Oliver Wyman. He can be reached at gregory.mackenzie@oliverwyman.com

Su Su is a senior manager at Oliver Wyman. She can be reached at su.su@oliverwyman.com.

Tina Guo is a consultant at Oliver Wyman. She can be reached at Tina.Guo@oliverwyman.com.