Medicare Advantage Expanded Supplemental Benefits Over the Years

By Jackie Lee

Health Watch, Special Edition, March 2021

Enrollment in 2020 Medicare Advantage (MA) plans was 24.1 million, comprising over one-third (36 percent) of all Medicare enrollees,[1] an annually increasing figure[2] for the last 15 years. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) projects MA enrollment in 2021 to increase to 26 million, with increased availability of plan choices and benefits.[3]

The CMS 2019 Announcement,[4] released in April 2018, expanded the scope of the primarily health related supplemental benefit standard. The new, broader reinterpretation provided more flexibility in designing MA plans, allowing insurers to offer additional benefit types beginning in Contract Year (CY) 2019 with goals of enhancing beneficiaries’ quality of life and improving health outcomes.

For CY 2021, CMS announced[5] an estimated 3 million MA enrollees across roughly 730 plans would benefit from these additional benefits among all Plan Benefit Package (PBP) categories. This focus will be on the frequency and enrollment of MA plans offering additional, or expanded, “other” supplemental benefits from CY 2019 through CY 2021 within PBP categories 13d-13f, including coverage increases and longevity year-over-year by benefit and category type. As part of this analysis, benefit categories and categorization were created based on an evaluation of individual benefits and determining similarities. The findings of this analysis are based solely on the public data for PBP category 13, with no consideration of factors outside the scope of this analysis, such as premiums, plan star ratings, or benefits categorized under other PBP categories.

Background: Benefit Reinterpretation and Summary of Changes in 2019 & 2020

CMS’ reinterpretation[4] of “primarily health related” supplemental benefits hinged on medical and health care research demonstrating that the value of an item or service can “diminish the impact of injuries or health conditions and reduce avoidable emergency and health care utilization.” The new interpretation meant an item or service “must diagnose, prevent, or treat an illness or injury, compensate for physical impairments, act to ameliorate the functional/psychological impact of injuries or health conditions, or reduce avoidable emergency and health care utilization.” In summary, an MA plan could provide a new supplemental benefit given it is a medically appropriate health care benefit, recommended by a licensed provider, and not for the sole purpose of inducing enrollment.

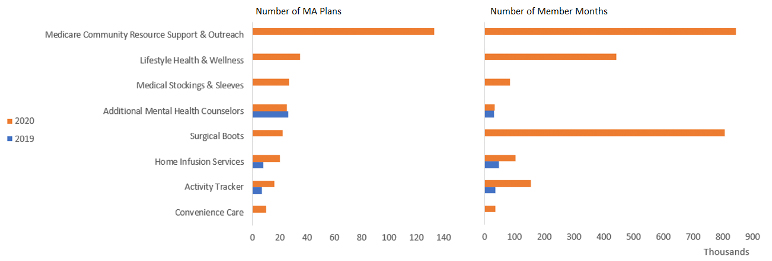

Insurers moved swiftly in their short time before summer to add a variety of benefits for CY 2019, when plans were expected to be finalized. Compared to CY 2018, “other” benefits[6] in CY 2019 increased by nearly three times, largely due to the addition of 20 new (expanded) benefits.[7] Figure 1 shows a summary [8,9] of the most common expanded benefits offered in both CY 2019 and CY 2020.

Figure 1

Summary of Most Common Expanded Benefits in CY 2019 and CY 2020

When comparing the growth rate of CY 2020 to CY 2018, the growth rate of “other” benefits was only 38.7 percent. [6] Among 17 aggregated insurers in CY 2019, an average of 1.1 supplemental (expanded) benefits fitting the reinterpretation were added within 614 plans.[7],[8],[9] The average expanded benefit increased in CY 2020 to 1.2, but the number of participating aggregated insurers and plans decreased to 13 and 304, respectively, representing a decline of just over 50 percent in plans with expanded benefits from CY 2019. [8,9] The number of beneficiaries with access to a plan containing expanded benefits also decreased in CY 2020 from CY 2019 by nearly 60 percent. [7]

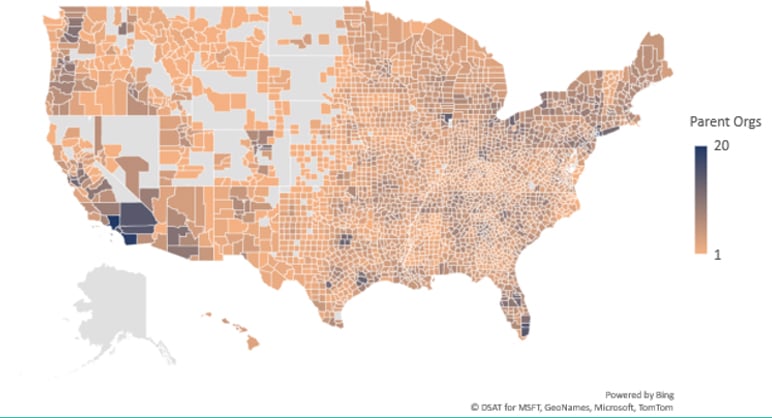

In CY 2019, insurers within some or all counties of 44 states offered expanded benefits in plans with subsequent non-zero enrollment, decreasing to just 33 states by CY 2020. During these two initial years of trialing a different mix of expanded benefits annually, insurer participation by county appeared to be the main driver of whether an expanded benefit was offered, rather than competition between insurers regarding a benefit type of benefit category. Figures 2 and 3 represent the total number of parent organizations and total number of parent organizations offering expanded benefits, respectively, by county in CY 2020 that had plans with non-zero enrollment. [7,8] These figures demonstrate that areas with higher insurer participation were more likely to offer an expanded benefit. Additionally, more urban rather than rural areas saw trends of higher insurer participation and were therefore more likely to have plans available within their counties offering expanded benefits.

Figure 2

Number of Parent Organizations by County in 2020

Figure 3

Number of Parent Organizations with Expanded Benefits by County in 2020

When reviewing the average expanded benefit by county compared to the parent organizations offering expanded benefits, we found a frequent inverse relationship, but this was an observation not the rule. For example, Indiana and Ohio each had one parent organization per county where expanded benefits were offered; however, counties in each state had higher averages of expanded benefits. Texas had one parent organization per county where expanded benefits were offered, and yet average expanded benefits trended higher in more urban counties. California seems to be the reverse of Texas. Insurers were clearly operating differently on a state-by-state basis regarding expanded benefit offerings.

Expansion of All “Other” Benefits and Expanded Benefits in CY 2021

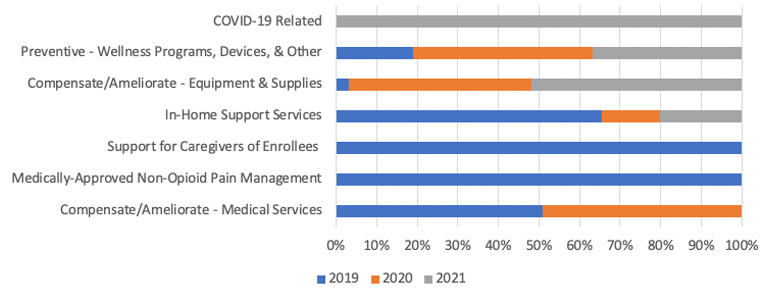

Consistent with CY 2020, the total number of aggregated insurers participating in CY 2021 increased to 14 with the average expanded benefit decreasing to 1.0 and plans offering these expanded benefits decreasing slightly by just over 2 percent. [8,9] COVID-19-related benefits occur in more than one out of every five plans in CY 2021, and in more than one out of every three plans with any benefit.[10] Of the plans with COVID-19-releated benefits, over 99 percent offer no additional expanded benefit. [7] Uncertainty remains whether any of the COVID-19-related benefits will persist beyond CY 2021, such as face masks.

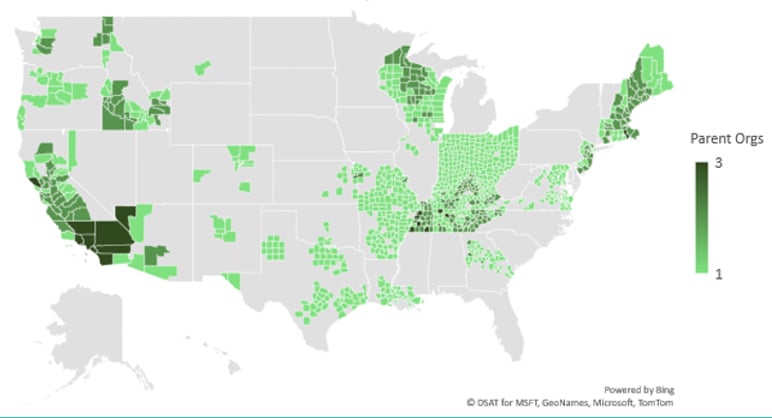

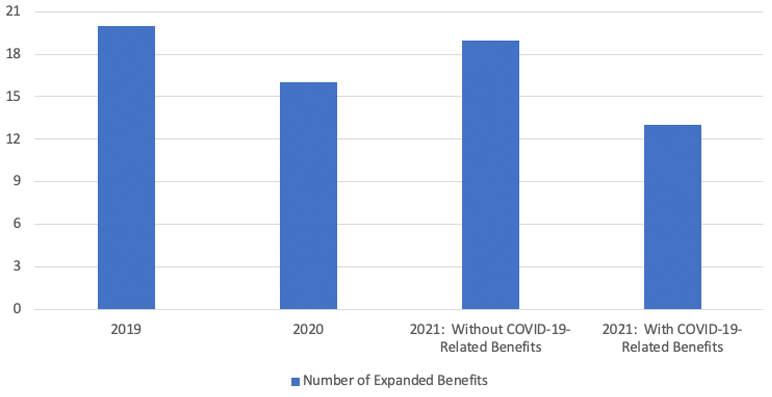

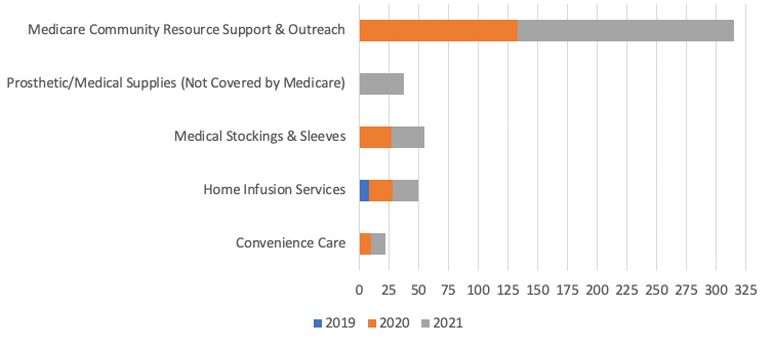

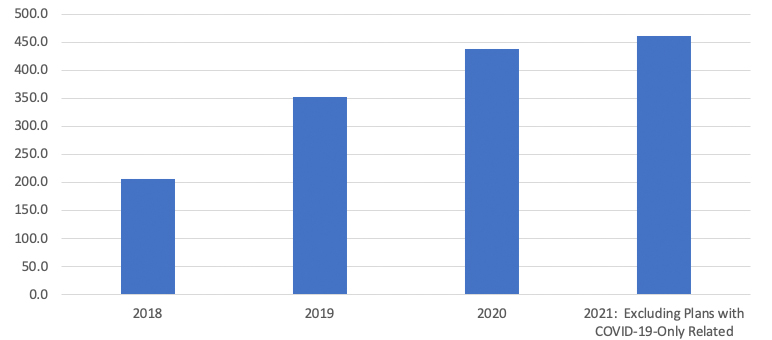

Outside of COVID-19, two benefit categories had a positive growth rate in plan availability from CY 2019 to CY 2021: Preventive (Wellness Programs, Devices, and Other) at 39.7 percent, and Compensate/Ameliorate (Equipment and Supplies) at 312.3 percent. Only the latter experienced a positive annual growth rate in both CY 2020 and CY 2021, with the two most common benefits in CY 2021 being compression garments (stockings and sleeves,) and prosthetic or medical supplies not covered by Medicare. Figure 4 shows a mix of the most common expanded benefit categories across all three plan years, and Figure 5 shows the change in total expanded benefits among all plans. [8]

Figure 4

Summary of Top Expanded Benefit Categories Year-Over-Year

Figure 5

Total Number of Expanded Benefits by Year

Only one of the 20 new expanded benefits in CY 2019 endured in both CY 2020 and CY 2021 plans: home infusion therapy (HIT) services. Plan availability for this benefit through CY 2021 increased significantly since CY 2019, with an overall growth rate over 62 percent. Classified under “In-Home Support Services,” a category which declined by nearly 80 percent among plans in CY 2020 compared to CY 2019, followed by an increase of 40.0 percent in CY 2021, HIT services provide beneficiaries the option of receiving critical treatments, such as chemotherapy, at home instead of a hospital, skilled nursing facility, or doctor’s office.[11] The services provided under the HIT benefit are distinct from those required and paid under the DME benefit, providing the complementary service component, such as professional visits, monitoring (including remote monitoring,) and various training and education services.[12],[13]

Of the benefits added in CY 2020, the Medicare Community Resource Support and Outreach benefit showed significant growth in plan availability in CY 2021, with the nearly 50 additional plans offering the benefit among 2 additional insurers. The benefit provides additional help from a designated team whose sole purpose is to inform and educate beneficiaries about community-based services and support programs aligned with available benefits.[14] Figure 6 shows the most common CY 2021 expanded benefits in comparison to the previous years.[7,8]

Figure 6

Summary of Most Common CY 2021 Benefits Year-Over-Year

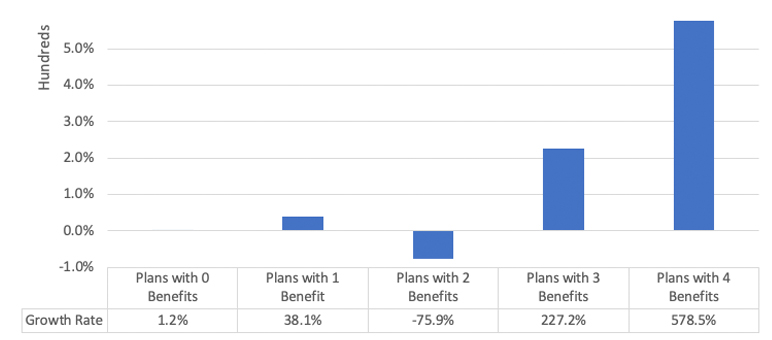

Membership in plans offering the highest number of benefits experienced the most significant growth rates through CY 2020.[8][15] The most significant enrollment growth rate in CY 2020 was nearly six times that of CY 2019 in plans with the maximum number of benefits,[15] and among plans offering expanded benefits,[7] those with the largest benefit mix also experienced the highest growth rate, at over 650 percent.[8] However, overall member months among plans with any expanded benefit declined by nearly 60 percent.[7,8] Figure 7 shows the member month growth rate among plans with each benefit mix from CY 2018, the year prior to the inclusion of expanded benefits, through CY 2020.[8,15]

Figure 7

Member Month (MM) Growth Rate: Pre-Expansion (CY 2018) to CY 2020

Recall a decline occurred in CY 2020 among states offering expanded benefits. Whether this trend continues is uncertain, but considering CY 2021 plans seem to contain primarily different expanded benefit types from previous years, the period of trial and error seems to be ongoing. This potentially signifies any expanded benefits offerings will be less likely to be driven by competition, and more likely continue to be driven by the prevalence of insurer participation or urban areas, where population density is greater, providing a suitable environment to trial new benefits.

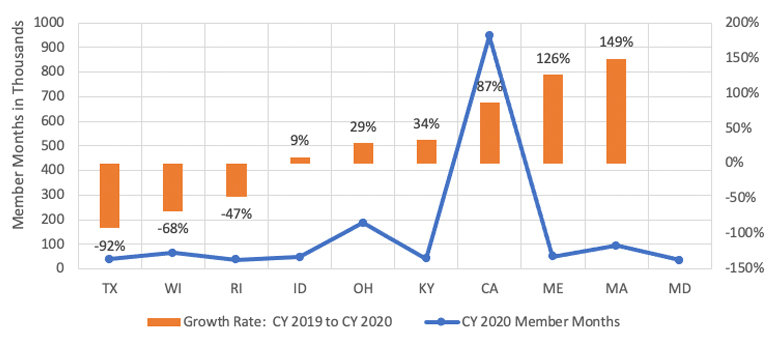

Among plans offering expanded benefits, most states experienced a decline in member month growth from CY 2019 to CY 2020.[8] However, 10 states made up the majority of the enrollment, as shown in Figure 8, along with the growth rate from CY 2019, and six of those states experienced an increase in CY 2020 from the previous year, making up nearly 80 percent of the enrollment in plans with expanded benefits.[16]

Figure 8

CY 2020 States with Top Member Months Including Growth Rate from CY 2019

Notably, insurers offering plans in CY 2018 that subsequently added expanded benefits to those plans in CY 2019 saw major declines in enrollment, by half or more, including states such as Florida, California and Pennsylvania. By CY 2020, California was one of the six states that saw a rebound in enrollment, but Florida and Pennsylvania no longer had any plans offering expanded benefits, and New York’s enrollment neared zero. Maryland and D.C. were unique cases where CY 2018 plans that subsequently offered expanded benefits in CY 2019 dropped to zero enrollment in CY 2019, but growth rebounded three-and-a-half to six times in CY 2020 compared to CY 2018.

Whether enrollment changes in states where plans offer expanded benefits is due to improved benefit mixes, the benefit types, or other area factors is uncertain, and more market research would need to occur. Figure 9 shows the average number of plans offering any mix of benefits, displaying an upward trend in the number plans offering benefits, with the most significant increase in CY 2019, and continually smaller annual increases in CY 2020 and CY 2021.

Figure 9

Average Number of Plans Offering Any Benefits

It is likely a combination of utilization, economies of scale, and net expenditures are key drivers in selection of expanded benefits. Undeniably evident as a beneficiary driver is the maximum variety of benefit availability.

Some Financial Considerations for Insurers in CY 2021

Although the goal of the expansion of the primarily health related supplemental benefits is to enhance beneficiaries’ quality of life and improve health outcomes, the goal of an insurer is to retain strong finances, as it is crucial to industry survival. Net costs are the result of a variety of sources, including rebates and claims.

In CY 2020, the average MA plan[17] is receiving $122 in rebates per member per month (PMPM) for cost-sharing reduction or supplemental benefit spending, the highest in the program’s history, up from $107 PMPM in CY 2019, or 14 percent.[18] Plans projected that an average of $22 PMPM (18 percent) of these rebates are used for Part A and Part B supplemental benefits. The amount will likely follow the ongoing trend of increasing for CY 2021, allowing more spending on supplemental benefits. For CY 2021, CMS amended the MA medical loss ratio (MLR) regulations to “allow MAOs to include all amounts paid for covered services, including amounts paid to individuals or entities that do not meet the definition of “provider” in alignment with changes to MA supplemental benefits.”[19]

Regarding the growing Home Infusion Services benefit, CY 2021 also introduces a new permanent payment change. Both CY 2019 and CY 2020 fell under a transitional payment for eligible home infusion suppliers for certain items and services under this benefit.[12] The permanent and transitional payments apply only to a subset of covered Part B DME infused drugs, but higher payment rates are set for initial visits to eligible home infusion suppliers as of CY 2021.[20]

Potential Changes Beyond CY 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic saw an influx of plans with “other” related benefits beyond the federally funded benefits Medicare covers, including Face Masks and Personal Protective Equipment.[21] CMS is temporarily encouraging MA organizations (MAOs) to waive or reduce cost sharing for benefits and services related to COVID-19 for all “similarly situated plan enrollees on a uniform basis.”[22] The caveat is the limit on cost sharing for COVID-19 testing, testing-related services, and vaccines (and their administration) only apply during the public emergency period. Insurers may find after the emergency period ends that current COVID-19-related benefits will be useful for some time under the new expanded supplemental benefits definition.

Furthermore, changes handed down from Congress could have a considerable impact on specific benefits, benefit mixes, or cost-effectiveness. In October 2020, a Medicare Payment Advisory (MedPAC) meeting discussed ideas of adjusting rebate percentages, or a new payment model to calculate MA payments, which would affect benchmarks by blending local and national spending, potentially improving lower income beneficiaries’ access and value to supplemental benefits.[23] No recommendation has been finalized, but concerns were addressed by some regarding supplemental coverage disruptions, and actual experience driving utilization of supplemental benefits.

What Should Your Organization Do?

As insurers continue to analyze the advantage of expanded supplemental benefits, it should be expected that ongoing updates to the benefit types being added and removed annually will occur. In preparing for CY 2022 and beyond, uncertainty will be dependent on utilization, health outcomes, and cost-effectiveness of the CY 2021 expanded benefits, including those related to COVID-19. Beneficiary demand has shown a larger benefit mix is preferred, but with an overall decrease in plans offering expanded benefits in CY 2020, the CY 2021 enrollment will expand the data beyond a single period[24] to help insurers determine where the demand perseveres among benefit categories and specific benefits.

As more time passes between the initial expansion, insurers will likely be doing their own research on the expanded benefits in their areas to determine how enrollment is responding to the availability of these expanded supplemental benefits. It will be interesting to continue observing to see if more carriers start these expanded offerings in the hopes of increased enrollment despite the fact that these supplemental benefits, per the definition, should not be offered for the sole purpose of inducing enrollment. With the enrollment in plans with multiple benefits increasing annually, additional time and consideration will help determine if an expanded benefit is truly providing a “health care benefit,” in order to determine if enrollment increases are the cause or effect of the benefit inclusion, or whether other factors could be influencing consumer behavior. These factors can be anything from premium changes, benefit changes in other PBP categories, such as dental or vision, or the prescription formulary.

Rebate increases will help finance the expanding mix of supplemental benefits, and the effects of the new MLR calculations as of CY 2021 will have lasting effects during the three-year rolling averages, regardless if new changes are made to the regulations in CY 2022 or beyond. Changes in typical industry areas, such as economies of scale, competition, technology, and diagnoses will have their own impacts on the changing expanded benefits and overall supplemental benefit mix. Insurers will need to be vigilant and meticulous in reviewing all underlying data as it becomes available, as well as factoring in potential drawbacks, to ensure success amid their expanded supplemental benefits, not only for their companies, but for the beneficiaries as well.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries or the respective authors’ employers.

Jackie Lee, FSA, MAAA, is a vice president and principal at Lewis & Ellis, Inc. She can be contacted at jlee@lewisellis.com.