Medicare Supplement and FASB’s Long-Duration Targeted Improvements Project Part II: Conclusions

By Rowen B. Bell

Health Watch, September 2021

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a two-part series. Part I is also published in this issue and can be found here.

In 2018, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) adopted significant revisions to the U.S. GAAP insurance accounting literature, via Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2018-12. The title of ASU 2018-12 is “Targeted Improvements to the Accounting for Long-Duration Contracts,” and as a result a common acronym for ASU 2018-12 is LDTI (long-duration targeted improvements).

Part I of this two-part article provided a brief refresher on LDTI, as well as an overview of relevant aspects of Medicare Supplement insurance and current GAAP accounting practice for this product. Now, Part II assembles the pieces into a discussion of how LDTI impacts Medicare Supplement.

Medicare Supplement Reserves under LDTI

When we pivot from current U.S. GAAP to LDTI and consider the implications for Medicare Supplement reserving, we need to grapple with the implications of three particular ways in which LDTI differs from current GAAP.

First, under LDTI the lock-in principle no longer applies. As discussed in Part I, the existence of the lock-in principle is fundamental to the conclusion under current GAAP that benefit reserves are unnecessary for attained-age-rated policies. So, in the absence of the lock-in principle, it is no longer immediately obvious that attained-age-rated Medicare Supplement policies do not need GAAP benefit reserves. Even if one believes at policy issuance that the loss ratio should remain flat over time, under LDTI one cannot “set and forget” that belief. Instead, the relationship between the expected future loss ratio and the expected lifetime loss ratio is regularly reevaluated, taking into account the emergence of actual experience as well as updated forecasts for the future.

Second, under LDTI it is now clear that the unit of account for reserve calculation—the cohort—cannot include policies issued more than one year apart. Moreover, it is made clear that each cohort’s reserve is floored at zero.

As discussed in Part I, for community-rated business the conclusion under current GAAP that benefit reserves are unnecessary depends not only on the lock-in principle, but also on considering the entire block as the relevant unit of account for measuring reserves. However, with LDTI, different issue years of policies need to be evaluated separately, even in a situation where the economics of the business are such that older issue years are being intentionally cross-subsidized by newer issue years, as may be the case for community-rated Medicare Supplement. With each cohort’s reserve being floored at zero, it is not possible under LDTI to use negative reserves from some issue years to offset positive reserves from other issue years—which in essence is the argument insurers have made historically, by thinking about a community-rated block on a blockwide basis.

Third, under LDTI the unpaid claim liability is no longer separate and distinct from the benefit reserve; instead, the two concepts are part of a single liability, even if the insurer elects to present the claim liability piece separately.

As a practical matter, insurers will likely want to continue calculating Medicare Supplement unpaid claim liabilities in a manner consistent with current practice (i.e., using claims triangle methods similar to those used for other lines of medical insurance), since separate claim liability calculations will still need to be performed for statutory accounting purposes. However, insurers will need to be able to apportion the results of those claim liability calculations to the different LDTI cohorts as an input into the benefit reserve calculations. It could therefore make sense for the insurer to modify its existing structure for performing claim liability calculations to better align that structure with its LDTI cohort structure.

Leaving aside such operational concerns, the newfound interaction between the unpaid claim liability and the benefit reserve under LDTI could have some unusual implications.

Suppose, for example, an insurer has a Medicare Supplement cohort for which the future expected loss ratio is less than its lifetime expected loss ratio. The insurer calculates that the LDTI benefit reserves—before consideration of future cash flows on previously incurred claims and before application of the zero floor—would be –$7 million. Suppose also that the insurer calculates its Medicare Supplement unpaid claim liabilities separately from the benefit reserves and has allocated $10 million of such claim liabilities to this cohort.

Under the AICPA’s interpretive guidance discussed in Part I, the insurer needs to consider both of these amounts together when determining the total liability for the cohort. In particular, the zero floor on the cohort’s liability is applied after taking the cash flows from unpaid claims into account, not before. As such, the total liability for this cohort is $3 million, not $10 million! In effect, $7 million of current claim liabilities gets absorbed by the otherwise unrecognizable negative reserves associated with future claims.

Where do these three observations leave us?

For issue-age-rated Medicare Supplement business, the LDTI changes to U.S. GAAP are a matter of degree, not kind. That statement does not minimize the effort involved in LDTI implementation for these products, particularly in moving from a locked-in model to one where the insurer needs to update the benefit reserves regularly to reflect both changes in future assumptions and differences between historical experience and previous expectations. But at the end of the day, issue-age-rated products had both benefit reserves and claim liabilities before LDTI, and the same will be true after LDTI, although the claim liabilities may or may not still be presented separately on the balance sheet.

In contrast, for attained-age-rated and community-rated Medicare Supplement business, LDTI disrupts the long-held tenet that these products only have claim liabilities and do not have benefit reserves. While it is possible that under some facts and circumstances the benefit reserves for these products will end up being zero, that conclusion is no longer preordained. As such, insurers will likely need to scope their attained-age-rated and community-rated Medicare Supplement blocks into their LDTI implementation process and prepare themselves to perform the same types of cash flow projections, assumption updates and benefit reserve calculations for these blocks as they will for their issue-age-rated Medicare Supplement blocks. That represents a significant change from current GAAP, under which these blocks have simply not been part of the benefit reserve valuation process.

Some insurers might wonder: Can we construct a plausibility argument, in light of how we expect to manage the business going forward, that would allow us to record zero benefit reserves for those blocks without going through all the work to build a robust LDTI valuation model? Unfortunately, the integration under LDTI of benefit reserves and unpaid claim liabilities into a single total liability makes such arguments problematic.

Consider a cohort of business where the insurer can argue, in an imprecise way, that the future expected loss ratio will be less than the lifetime loss ratio. If the unpaid claim liability were completely separate from the benefit reserves, then that argument might represent sufficient evidence to allow the insurer to record zero benefit reserves for the cohort in light of the zero floor. However, as discussed earlier, the zero floor needs to be applied to the cohort’s total liability, inclusive of its unpaid claim liability. As such, it is not enough to say “we are confident that this cohort’s benefit reserve, exclusive of unpaid claims, would be negative if we were to calculate it.” The insurer would need to quantify how negative it would be in order to know how much of the separately calculated unpaid claim liability gets offset by negative benefit reserves in the process of applying the zero floor to the total liability.

As such, under LDTI, insurers need to develop and update projections of future premiums and claims for their attained-age-rated and community-rated Medicare Supplement business separately by issue year, just as they do for their issue-age-rated business. While such projections may have been made historically to support the insurer’s loss recognition testing, under LDTI these projection assumptions will warrant greater scrutiny and precision, since these assumptions now directly impact the estimation of reserves on an ongoing basis, instead of only being relevant in the exceedingly rare case that loss recognition was triggered.

In that regard, the long-term projection of future premium increases for a community-rated block poses a particularly unusual challenge. As discussed in Part I, here future premium increases will seek to reflect the impact on the block’s expected claims of the yearly change in the average age of the block, which in turn is influenced by the flow of new business into the block. As such, to accurately project future premiums on existing community-rated policies, the insurer may need to make assumptions regarding volumes of new business well out into the future to form a view on how the average age of the block will evolve over the future lifetime of existing policies. In this manner, an insurer’s LDTI benefit reserves for community-rated Medicare Supplement appear to depend partially on its expectations regarding future sales volumes—an unusual consequence of the application of the LDTI paradigm to this particular long-duration product.

One last topic of interest is the insurer’s determination of its Medicare Supplement cohort structure. As discussed in Part I, the guidance is clear that a single cohort cannot include policies issued more than 12 months apart. However, beyond that, the insurer may have significant latitude to organize its cohort structure as it sees fit.

For instance, should the insurer have one set of cohorts for its issue-age-rated Medicare Supplement business plus a second set for its attained-age-rated business, or should it instead have a single set of cohorts that commingle both issue-age-rated and attained-age-rated policies? Either structure appears to be defensible as an accounting policy choice, and it is not self-evident that one would always lead to lower total liabilities than the other. As such, insurers may wish to wait until after they’ve built their Medicare Supplement LDTI models and reviewed some output before deciding on the precise details of their cohort structure.

Medicare Supplement DAC under LDTI

In this discussion, for simplicity, we are ignoring acquisition costs other than brokerage commissions and are focusing only on commission-related DAC.

As discussed in Part I, a typical Medicare Supplement policy has a declining ratio of actual commissions to premiums over its lifetime, to the extent that each year’s commissions are calculated as a percentage of first-year premium (with that percentage likely itself declining over time) whereas premiums are increasing every year. Consequently, under current GAAP, DAC capitalization and amortization represent a vehicle by which the insurer achieves something resembling a level ratio of commissions to premiums over its lifetime.

Before turning to the implications of LDTI for Medicare Supplement DAC, we start by discussing current practice in greater depth. One question that occasionally arises under current GAAP: Is the insurer deferring all of its commission expense or only the excess of current commissions over some ultimate level? While current practice appears to vary, the answer is that on some level it has not mattered all that much how you think about it.

We can illustrate this with a simplified example, using the following assumptions:

- First-year premium = $150 per member per month.

- Annual premium increases = 5 percent per year.

- First-year commission = 20 percent of first-year premium.

- Renewal commissions = 7 percent of first-year premium.

- All policy terminations occur at the end of the year; termination rates are 10 percent at the end of years 1 through 4 and 100 percent at the end of year 5.

- Interest rate of 3 percent.

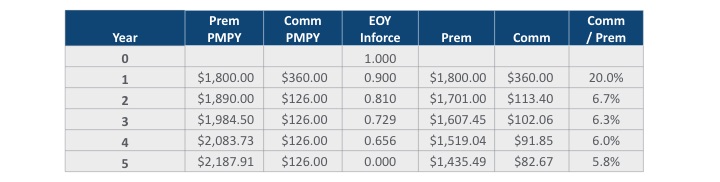

With these assumptions, the premium and commission cash flows over the five-year lifetime of the policy are expected to look those shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Five-Year Premium and Commission Cash Flows

Note that, as discussed earlier, the commission-to-premium ratio keeps declining even after the point in time (here, year 2) at which the per-member commission becomes level in dollar terms.

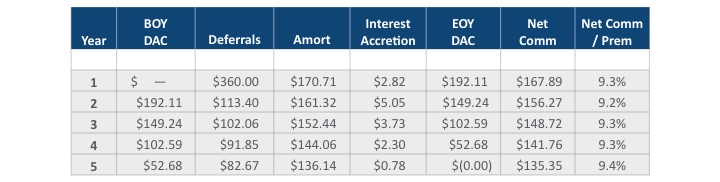

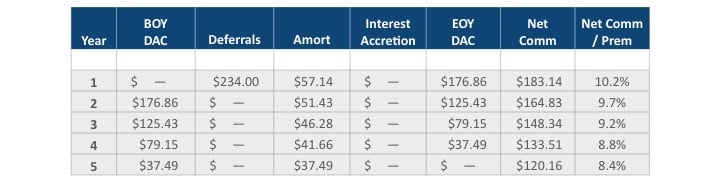

We consider three different approaches that an insurer might take today to estimating DAC, given these facts. In version A, the insurer defers all of each year’s commissions, amortizing the DAC asset in proportion to premiums and accreting interest on DAC. This essentially levelizes the relationship between net (i.e., post-DAC) commission expense and premium over the lifetime of the product, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Version A—Defer Everything

In version B, instead of deferring all commissions, the insurer defers only the excess of the current year’s commissions over the ultimate commissions defined in percentage-of-premium terms. That is, each year’s deferrable commissions are defined to be the current year’s commissions, less the current year’s premiums multiplied by the expected commission-to-premium ratio from the final year of the projection (i.e., the 5.8 percent from the year 5 row of Table 1). This leads to deferrals in every year of the projection except the final one, although each year’s deferrals are less than the amounts shown in version A for the same year. However, as shown in Table 3, version B mathematically leads to exactly the same DAC asset balances and annual net commission expense as version A throughout the entire projection period.

Table 3

Version B—Defer Excess over Final Year, in % Terms

As such, under current GAAP it does not really matter whether you defer all commissions or only the excess of current commissions over the ultimate commissions, assuming you’ve defined “ultimate commissions” in percentage-of-premium terms.

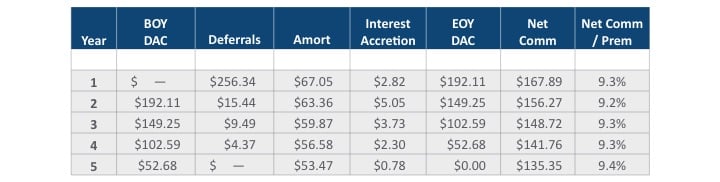

A third alternative today is version C, in which the insurer defers the excess of the current year’s commissions over the per-member ultimate commissions, as opposed to the percentage-of-premium ultimate commissions. In this example, that means the insurer only makes deferrals in the first year of the projection, since the per-member commissions flatten out starting in year two. Relative to versions A and B, as shown below version C produces lower DAC asset balances and a slightly declining slope over time in the ratio of net commissions expense to premiums, because the non-deferrable commissions are the same in dollar terms every year and thus represent a declining percentage of premium over time (unlike version B where the non-deferrable commissions are the same percentage of premium each year)

Table 4

Version C—Defer Excess over Final Year, in $ Terms

With these illustrations of historical DAC practices in mind, we now turn to LDTI considerations, making two main observations.

First, under LDTI it is now clear that of the three approaches outlined for determining deferrable commissions, only the third is correct going forward. Commissions that are level from period to period, like the commissions in year 2 and beyond in our example, are now specifically called out as being not deferrable.

In the illustration, the differences between the LDTI-compliant approach (version C) and the other approaches (versions A and B) were not profound. However, with other fact patterns, the new guidance on nondeferrable commission expense could have a much more significant impact. For example, suppose that the commissions in each year are defined to be 15 percent of first-year premium. In dollar terms, the per-member commissions are the same in every year. Thus, under LDTI, none of these commissions would be deferrable, and there would be no DAC asset arising from commissions. This could be a significant change from current GAAP, where the insurer would likely have argued that the declining commission-to-premium ratio over time justifies the deferral of commissions.

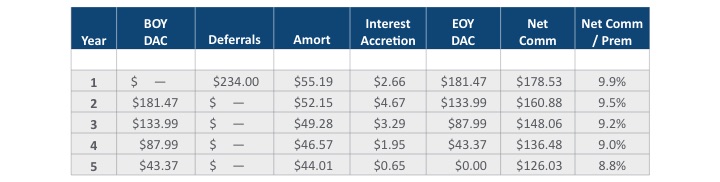

Second, under LDTI the amortization of DAC can no longer be performed in relation to premiums but instead needs to be performed “on a straight-line basis.” This is generally believed to allow an insurer to amortize DAC in relation to the amount of insurance in force, which for Medicare Supplement would mean in relation to the number of lives in force. Also, under LDTI the DAC no longer accretes interest.

In the simplified example we have been considering, changing the amortization pattern from premiums to members in force and eliminating the accretion of interest on DAC to create version D does not make a tremendous difference, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5

Version D—LDTI

However, in more realistic examples, the difference in DAC amortization patterns between LDTI and current GAAP becomes much more significant.

Consider the following variation on our earlier example, with those assumptions that are not restated remaining the same as they were before:

- Renewal commissions = 20 percent of first-year premium in each of years 1 through 6 and 7 percent of first-year premium in each of years 7 and beyond.

- All policy terminations occur at the end of the year; termination rates are 10 percent at the end of years 1 through 34 and 100 percent at the end of year 35.

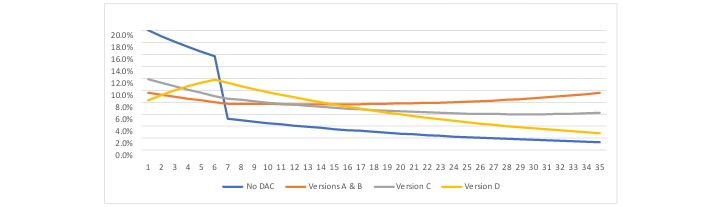

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the commission-to-premium ratio over the 35-year projection period for this modified example, under four different calculation approaches:

- The “No DAC” line shows the ratio before considering any deferral and amortization of commissions (i.e., consistent with statutory accounting).

- The “Versions A & B” line shows the ratio under current GAAP, assuming that all commissions are deferred (or equivalently that all commissions in excess of the year-35 percentage-of-premium rate are deferred).

- The “Version C” line shows the ratio under current GAAP, assuming that only the excess commissions in the first five years, before the per-member dollar commission amount stabilizes, are deferred.

- The “Version D” line shows the ratio under LDTI, using the same deferrals as in version C, but with DAC amortization done in proportion to lives in force and no accretion of interest on DAC.

Interestingly, in this example the shape of the LDTI curve (version D) is rather different from under current GAAP (either versions A & B or version C). Under LDTI, the ratio of net commission expense to premiums actually increases steadily throughout the course of the first six years, before commissions reach their ultimate level, which is directionally different than what happens under current GAAP.

Figure 1

Net Commission/Premium Ratio

As such, we are left with the conclusion that the LDTI approach to commission deferral and DAC amortization, when applied to a typical Medicare Supplement fact pattern, will likely create some noticeable differences from current GAAP with respect to the timing at which GAAP earnings emerge over the lifetime of the product. In this illustration, focusing just on commission DAC and ignoring any implications from benefit reserves, LDTI creates higher expected GAAP earnings than current GAAP at the very beginning of the contract and also over the latter half of the contract’s expected lifetime, at the cost of lower expected GAAP earnings in the intermediate period.

Conclusion

The intent of this two-part article was to increase the level of understanding within the health actuarial community of ways in which LDTI implementation may uniquely impact the Medicare Supplement line of business. There is admittedly much more to LDTI implementation than the topics we have chosen to highlight here. As health insurers navigate this territory, frequent communication with the insurer’s audit firm is encouraged.

In summation, we want to leave the reader with three main takeaways regarding LDTI and Medicare Supplement:

- Under LDTI, attained-age-rated and community-rated Medicare Supplement policies can no longer be thought of as being “out of scope” for the benefit reserve valuation process.

- LDTI reserving for Medicare Supplement is complicated by two technical nuances and the interplay between them: first, the requirement to calculate benefit reserves separately for each issue year, with a zero reserve floor for each issue year; and second, the AICPA’s interpretation that the unpaid claim liability is part of, and not separate from, the benefit reserve.

- Changes between current GAAP and LDTI in the requirements for how broker commissions are capitalized and amortized will drive changes in the timing of when GAAP profits are expected to emerge over the lifetime of a Medicare Supplement policy.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual author and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the author’s employer. The author expresses his thanks to Rob Frasca, Bob Hanes, and Ken Clark for their comments on drafts of this article.

Rowen B. Bell, FSA, MAAA, is a managing director in the Insurance and Actuarial Advisory Services practice of Ernst & Young. He can be reached at rowen.bell@ey.com.