Restoring the Indifference Ideal: If It’s Not Adjusting for “Risk,” It’s Not “Risk Adjustment”

By Greg Fann

Health Watch, June 2022

The aim of ACA risk adjustment is to foster the development of markets where health plans compete on quality, efficiency, and value, not on risk selection.[1]

The appropriate selection of attributes that impact risk levels is a fundamental tenet of actuarial practice. Actuarial Standard of Practice (ASOP) No. 12 (Risk Classification) states, “The actuary should select risk characteristics that are related to expected outcomes. A relationship between a risk characteristic and an expected outcome, such as cost, is demonstrated if it can be shown that the variation in actual or reasonably anticipated experience correlates to the risk characteristic . . . Rates within a risk classification system would be considered equitable if differences in rates reflect material differences in expected cost for risk characteristics.” It is the job of actuaries not only to identify risk characteristics but also to provide quantifying assessments of risk differences. In the rating of health insurance products, this interpretation is clear; premium rating factors should reflect expected medical claim cost differences. For example, as health care costs materially increase with age, age should be a risk characteristic used in rating, and rating factors should generally increase with age.

In loosely regulated environments, health plans generally have the flexibility (and the obligation) to develop appropriate rating factors. Theoretically, health plans are indifferent to enrollment mix if rating factors are developed to promote actuarial equity and level profitability across various demographic characteristics and products; this is the “indifference ideal.” This tenet is also characterized as insurers being “ambivalent to any characteristics (such as age, income level, health status, or preferred metal tier).”[2]

As a practical matter, some rating cells are often more lucrative than others and health plan actuaries generally have a strong understanding of granular financial performance. With this insight, health plans may refine their rating factors or remain incented to aggressively sell profitable business segments.[3] In any event, there has always been some element of risk selection in traditional health insurance markets to combat the indifference ideal.

The World of ACA

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) created a paradigm shift. In the ACA world, health plans are not permitted to develop rating factors that properly reflect risk. Rather, some rating factors are regulatorily prescribed (e.g., age), while some rating characteristics (e.g., health status, gender) are not allowed. It is no longer the job of health plan actuaries to provide quantifying assessments of risk differences in the rate development for these traditional risk characteristics. This framework change does not present an ethical dilemma for actuaries, as the law should always be followed when it conflicts with ASOP guidance, but it does introduce a market challenge.

There is a rating gap between the premium rates offered under the current market regulatory environment and the premium rates that would have been offered in an environment without regulations limiting rating factors. ‘Risk adjustment’ is a mechanism which is designed to directly bridge that gap. Health plans no longer develop rating factors that are regulatorily prescribed; instead, the federal government assumes responsibility for the development of these factors and associated adjustments.[4] There is a change not only in what consumers pay for health benefit coverage, but in who is responsible for risk classification and risk assessment. The current role of health plans in rate development is not to evaluate risk associated with premium-constrained risk characteristics, but to accept the results of the risk adjustment mechanism and compete on quality and efficiency rather than an ability to distinguish risk levels between prospective marketplace enrollees. Ideally this would be accomplished as the indifference ideal that is disrupted by rating regulations would be restored by a risk adjustment mechanism.

Risk is a broad term in the insurance lexicon, and it is important to understand its narrow meaning in the phrase “risk adjustment.” This can easily be accomplished by asking, What specifically is it that “risk adjustment” is trying to adjust? In the context of risk adjustment in a regulated health insurance environment, risk effectively arises from premium rates being detached from risk characteristics due to rating regulations. Risk exposure is understood, not as a consequence of potential adverse deviation, but as a reflection of the impact of regulatory constraints that can impede the proper reflection of risk characteristics in premium rate development. From an influential perspective, risk adjustment is an attempt to allow regulated premiums to better reflect actuarial equity through a financial mechanism that helps to curtail incentives for risk selection.

In this influential sense, the risk adjustment mechanism is intended to provide financial support to regulatory actions that have moved rating factors away from actuarial equity. The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) states it this way, “The ACA’s risk adjustment program is intended to reinforce market rules that prohibit risk selection by insurers. Risk adjustment accomplishes this by transferring funds from plans with lower-risk enrollees to plans with higher-risk enrollees. The goal of the risk adjustment program is to encourage insurers to compete based on the value and efficiency of their plans rather than by attracting healthier enrollees.”[5] Accordingly, the combination of rating in accordance with ACA rules and a well-functioning risk adjustment mechanism should result in a stable marketplace with compliant, actuarially sound premiums.

Bridging the Gap

Adjusting for risk is framed as “bridging the gap” between “premiums with risk selection” and “premiums without risk selection.”[6] In general, the risk adjustment mechanism is designed to bridge the gap between allowable rating factors and factors that would otherwise be applied without rating limitations. Consequently, the ACA risk adjustment methodology needs to be developed with both a detailed understanding of risk characteristics and a technical comprehension of how the ACA regulatory limitations on premium rates reflect these risk characteristics. If the gap generated by regulatory limitations is unclear, it is likewise unclear how to construct the appropriate bridge.

To illustrate, consider a simple example with two health plans and two enrollees, a younger adult and an older adult. In a loosely regulated environment, the younger adult premium is $100 and the older adult premium is $500; the premiums reflect the underlying cost difference. In a regulatory environment where age-based rates are not allowed, the premiums for both adults are $300. If one health plan enrolls the young adult and the other health plan enrolls the older adult, there is a clear mismatch between premiums and underlying costs. A mechanism that transfers $200 from the insurer enrolling the younger adult to the insurer enrolling the older adult would “bridge the gap,” properly adjust for risk and generate actuarially equitable results. This is the basic intent of risk adjustment.

Translating this example to the ACA world of restricted premiums, the absence of risk adjustment would be inequitable. A $200 transfer would also be inequitable because the ACA allows premium rates to vary by age; in fact, it prescribes the rate variation. A younger adult could end up paying a premium of $150 while an older adult would pay a premium of $450, as rate relationships are fixed to a 3:1 ratio. A transfer payment of $50 rather than $200 would then be required to generate equity.

The risk adjustment methodology must be deliberately designed to align with rating rules. As stated in an American Academy of Actuaries Issue Brief, “Risk adjustment is used to ensure that plans receive adequate payments when rating restrictions limit the extent to which premiums are allowed to vary by known risk factors. Therefore, it is important to align the risk-adjustment methodology with the underlying premium-rate development.”[7]

Without proper recognition of the ACA age factors, transferring $200 might seem appropriate as it reflects the cost difference, but such a transfer does not represent the risk as we are required to define risk as the difference between the allowable rating factors and the factors that would have been applied absent the rating rules. If we were asked to opine on methodology that transferred $200, we would rightfully conclude that the methodology would not qualify as risk adjustment if we properly understood ACA rating rules; such an incongruent transfer payment would only provide market complications and not reinforce ACA rating rules; in other words, it would create a new gap rather than bridging the gap created by the current ACA rules. The binary market implications of such a mismatch are a compliant environment where health plans would be incented to attract higher-age enrollees or a marketplace of unenforced rules where age-based premium rates would deviate from the prescribed age factors and generally not vary by age, in alignment with transfer payments reflective of cost rather than risk.

As a matter of practicality, development of an ideal model construct to achieve the primary goal of bridging the gap with precision is extremely difficult. Perfection is unachievable, and there will always be perceptions of biases in the risk adjustment methodology. We should acknowledge that the risk adjustment methodology need not be perfect to be recognized as risk adjustment, only that it be designed to correctly bridge the gap between allowable rating factors within the current regulatory environment and actuarially equitable factors developed without regulatory constraints. Any assessment of ACA risk adjustment efficacy must include the impact of ACA rating rules as its primary input. Using the example above, measuring the effectiveness of risk adjustment methodology by comparing it to the $200 transfer in an ACA regulatory environment is a flawed assessment because in the example above, the risk difference requires an adjustment of $50 rather than $200. In summary, assessments of risk adjustment efficacy must be conducted with a proper construction of allowable rating factors.

ACA Risk Adjustment Application

Consistent with the title “Plan Liability Risk Score (PLRS)” in the ACA risk adjustment methodology, risk scores reflect health plans’ plan liability associated with each enrollee. A change in individual market regulatory dynamics occurred in October 2017, causing the plan liability and associated premiums to change for many marketplace enrollees. The defunding of cost-sharing reduction (CSR) payments increased the plan liability of on-exchange silver plans.[8] Beginning in plan year 2018, silver plan premiums reflected higher plan liability, also described as higher actuarial value.[9]

Under the ACA’s single risk pool construct, allowable rating differences between benefit plans are limited to the “Actuarial Value and Cost-Sharing Design of the Plan.” Effectively, this means that price differences between benefit plans can be explained by benefit differences between plans, rather than different risk characteristics of populations expected to enroll in each plan. To properly bridge the gap, the risk adjustment methodology must conform to the rating rules rather than the other way around; there is no accommodation or allowance for altering rating factors to “be the bridge” to align with the ACA risk adjustment methodology. Stated another way, risk adjustment is the final step in the process, not an input into the rating formula to develop plan factors. Health plans that utilize perceived risk adjustment imbalances to deviate from the allowable rating relationships associated with benefit value are engaging in the textbook risk selection that ACA framers specifically sought to avoid.

Allowable Rating Factors

Allowable rating factors are predicated on actuarial value[10] and not metal level. The plan benefits determine the plan’s actuarial value and associated induced demand; the metal level is merely a label that does not impact plan value or the rate development. In the risk adjustment methodology, a mechanical simplification groups plans by metal level (intended to roughly group plans of similar actuarial value) and assigns risk coefficients. This grouping was reasonable and practical prior to 2018. Beginning in 2018, silver plan CSR 87 and CSR 94 variants had increased plan liability and effectively had actuarial values more in line with platinum level plans.

The rating and risk adjustment implications of CSR defunding are straightforward in a single risk pool regulatory environment. If a health plan offers a platinum plan with 87 percent actuarial value and a silver plan composed exclusively of CSR 87 enrollees with benefits identical to the platinum plan, the price of the silver plan and the platinum plan should be equivalent as premiums must reflect the same benefits rather than different populations expected to enroll in each plan. Accordingly, properly functioning risk adjustment methodology would reflect the rating rules and the varying risk characteristics between the silver and platinum plan enrollees such that health plans would be indifferent between attracting silver and platinum enrollees at the same price.

Risk Adjustment and CSR Enrollees

It is important to reaffirm that the risk adjustment aim is not merely to “transfer funds from plans with lower-risk enrollees to plans with higher-risk enrollees,” but to more broadly complement the rating rules by offsetting all ”variations in plan actuarial risk due to risk selection, beyond the premiums plans are able to collect.”[11] Only prescribed rating factors are allowed, leaving the risk adjustment mechanism with the comprehensive role of bridging regulatorily constrained premiums and actuarial risk.

The risk adjustment methodology has arguably been the least precise in bridging the gap for CSR 87 and CSR 94 enrollees, as claim costs have been significantly overpredicted and health plans have responded by lowering silver plan premiums relative to other metal levels. These dynamics are not transparently understood as CSR defunding resulted in an offsetting impact in 2018 with wide state variances. The general public understanding is that CSR defunding was an unanticipated change in the ACA regulatory environment that required modifications of ACA rules, created market uncertainty and required responses that created a variety of different scenarios. Therefore, current variations in the marketplace are primarily the result of unpredictable deviation and different state responses to CSR defunding. But that is neither the real history nor the market environment today.

Despite proclamations of market uncertainty, the plan liability dynamics of CSR defunding were documented and the legal implications were clear. Before CSR defunding occurred, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) publicly recognized the platinum level nature of CSR 87 and CSR 94 variants from both a rating and a risk adjustment perspective. In a 2015 Issue Brief, HHS explained the rating impact of CSR defunding, “The result would be a new distribution of consumers across Marketplace health plans, with silver plans likely enrolling only those individuals eligible for the two highest CSR tiers. Without enrollees at the 70 and 73 percent AV [actuarial value] levels, silver plans would have to be priced even higher to cover insurers’ costs. Specifically, with all enrollees entitled to 87 or 94 percent AV coverage, the new average AV in silver plans would be about 90 percent, and plans would have to be priced accordingly [my italics]. That would require . . . silver plan premiums to cover an AV of about 90 percent, rather than an AV of 70 percent.”[12]

In 2017, HHS issued a bulletin that proposed a change in the risk adjustment methodology to reflect the silver premium rating changes. The bulletin read, “Beginning for the 2018 benefit year, we intend to propose to apply the platinum metal tier risk adjustment model coefficients for the 87 percent and 94 percent cost-sharing reduction plan variants. For the risk adjustment transfer formula, we intend to propose considering the 87 percent and 94 percent silver plan variants (as well as the limited cost-sharing and zero cost-sharing variants) to have plan metal level actuarial values of 0.9 in order to account for the higher relative actuarial risk associated with these plans.”[13] Effectively, this change would better align the risk adjustment methodology with ACA rating rules by reflecting the change in plan liability of silver CSR 87 and CSR 94 variants.

While HHS did not follow through on this proposal after CSR defunding in October 2017, this inaction had no impact on the legislatively developed ACA rating rules. It is important to remember that risk adjustment must be designed to bridge the gap, because ACA rating rules are independent of the risk adjustment methodology; rating cannot be modified to bridge the gap to reflect the risk adjustment methodology. It is a one-way bridge; risk adjustment must be designed to bridge the gap between allowable ACA rating factors and rating factors that would be developed absent the ACA rating rules. In essence, ACA rating rules are independent of the risk adjustment methodology’s treatment of silver CSR 87 and CSR 94 enrollees.

The resulting disconnect between rating rules and risk adjustment is reminiscent of our example of a $200 transfer payment when $50 was the appropriate amount under ACA rating rules. In this environment, do health plans accept the disconnect and adhere to strict ACA rating rules, or are rating rules relaxed to accommodate the risk adjustment methodology, effectively bridging the gap from the wrong direction?

Until recently, there has not been a great deal of actuarial or HHS commentary or discussion about this misalignment. In October 2021, HHS vocally raised the issue in Appendix A of a Technical Paper, asking for feedback on using “the platinum risk adjustment model factors to calculate risk scores for CSR enrollees in the 87 percent, 94 percent, zero cost sharing, and limited cost sharing plan variants.”[14] In the paper, HHS clarified that such methodology changes would likely occur no earlier than plan year 2024. As the topic is actuarial in nature and the potential liberty presumed to interpret rating rules as flexible to accommodate a risk adjustment mismatch raises professionalism concerns, it is important that health actuaries understand these considerations and properly inform HHS and other stakeholders of potential policy implications. The remainder of this article discusses the historical dynamics, ACA rating compliance and associated considerations of changes to the risk adjustment methodology to better reflect plan liability and bridge the gap between allowable rating factors with ACA limitations and rating factors that would otherwise be applied.

Premium Misalignment

Following up on the question above with benefit of hindsight, have health plans implemented risk selection in reaction to a disconnect between ACA rating rules and risk adjustment methodology? In its Technical Paper, HHS acknowledges it has received comments explaining risk selection dynamics: “issuers are setting the silver plan premiums low to attract these CSR enrollees due to a perceived overcompensation in the risk term in the state payment transfer formula that may occur for some issuers . . . The commenters suggested that HHS should take action to address this misalignment, which they contend would reduce premium costs for 97 percent of Exchange enrollees.”[15] This scrambling of premiums involves ACA marketplace issuers playing an unfair game that is to the detriment of consumers. Its strength of influence can be seen by evaluating relative risk scores[16] and underlying costs. This practice of risk selection is a diversion from the ACA’s modified community rating rules; effectively, metal level premiums are influenced by enrollment characteristics of populations expected to enroll in each level in addition to benefits.

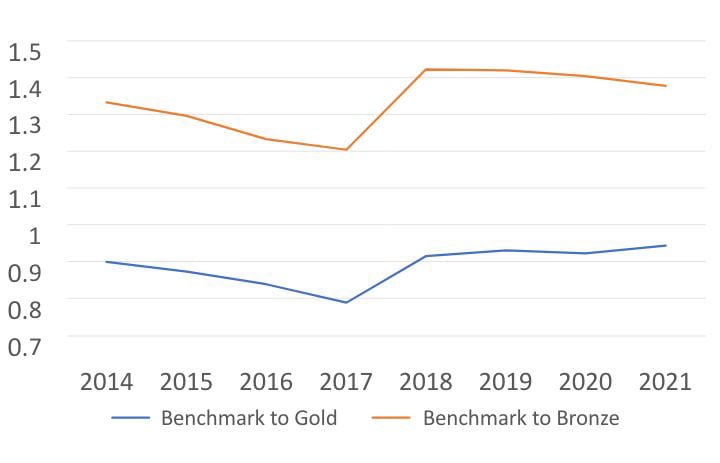

While CSR defunding has prompted much of the discussion regarding the ACA rating rules and the risk adjustment disconnect, metal level risk selection was practiced in ACA markets before 2018.[17] As risk adjustment has always been viewed as imprecise, there were financial incentives to bridge the gap by altering rating factors to better align metal level profitability beginning in 2015. Reflective of this realization, silver plan premiums consistently declined relative to bronze and gold premiums from 2014 to 2017. To achieve this, risk adjustment results have effectively been used as an input into metal level experience rating formulas. Figure 1 clearly demonstrates this pattern; while metal level risk selection continued after 2017, some transparency was lost as silver premiums were increased to reflect CSR defunding. A detailed review of rate filings and explanatory comments provided during the regulatory rate review process provide additional detail and clarification regarding actuarial rationale.

Figure 1

Benchmark Silver vs. Lowest-Cost Bronze and Gold Premiums

The metal level risk selection rating practices resulting in misaligned premiums can interchangeably be characterized as health status rating or experience rating (as opposed to modified community rating). With reference to the single risk pool regulatory framework, Stan Dorn, director of the National Center for Coverage Innovation at Families USA, explains that metal level pricing deviation “goes really to the heart of the ACA’s insurance reforms, the protection of people with pre-existing conditions and the prohibition of discrimination . . . When you charge premiums, you shouldn’t be looking at the risk level of that individual consumer signing up for coverage. You should not be looking at the risk level of the people enrolled in a particular plan. You should be looking ‘market-wide’ at what that risk level is.”[18]

In an actuarial study note I authored, I highlighted that there was initial reticence to accept some mathematical and market realities of the ACA. This appears to be changing.[19] Comments from stakeholders suggest that acknowledging deviation from ACA rating rules is no longer a controversial disclosure. In analyzing the impact of CSR defunding in 2017, the Congressional Budget Office described the nature of health status rating as follows: “For gold plans in the marketplaces, the agencies project that gross premiums would be modestly lower under the policy because those plans would attract a larger share of healthier people. Federal risk-adjustment payments aim to compensate insurers whose plans cover less healthy people, but the payments can address the risk only imperfectly.”[20] Likewise, the Risk Sharing Subcommittee of the American Academy of Actuaries states that risk adjustment results in an additional rating factor:

Both anecdotal evidence and Affordable Care Act (ACA) risk adjustment research indicate that the ACA’s risk adjustment structure generally overcompensates issuers for enrollees with risk adjustment-eligible conditions and undercompensates issuers for enrollees without risk adjustment-eligible conditions. This may not be optimal from a risk stabilization perspective, as material misalignments between risk adjustment results and the underlying risk of the population could result in issuers incorporating an additional risk premium into their rate filings to offset the increased uncertainty in financial outcomes . . . (this) puts significant pressure on plans participating in the individual market to be the lowest cost or second-lowest-cost silver plan in order to obtain these enrollees, as their favorable risk adjustment experience would then ultimately make it possible to reduce premiums further while putting additional strain on financial performance of issuers who fail to meet this threshold.[21]

In practice, the risk adjustment methodology is generally not recognized as bridging any gap; rather it is understood as creating a different gap that actuaries spend significant time trying to quantify. Effectively, risk adjustment results, not intended to play an allowed role in developing rating factors,[22] are being used as a key input in metal level risk selection rating formulas.

State Action

Premium alignment issues and metal level risk selection issues have not gone unnoticed. While ACA rating rules are federal in nature, states are generally responsible for rate review and regulatory enforcement. HHS offers guidance but largely defers to states with “effective rate review” processes for rule enforcement. As the rating dynamics associated with actuarial value are technical and paradoxical,[23] the comprehensiveness and rigor of each state’s review processes vary in detail and in nature. Accordingly, metal level premium relationships are disparate across the country.

Some states have specifically addressed premium alignment issues through formal rulemaking. In 2020, Colorado recognized marketplace experience rating and passed a law that said, “The commissioner may adopt rules designed to: Assure premium pricing that complies with the requirements in the federal act for modified community rating.”[24] A 2021 Texas law brought the rate review process back to the state level; a summary of that law highlights that Texas will “remedy a misalignment in premiums across the different metal tiers of coverage in the health insurance marketplace” through “focused rate review.”[25] New Mexico adopted new rating guidance for plan year 2022 that requires silver plan pricing to reflect the pure actuarial value and cost-sharing design associated with silver CSR 87 and CSR 94 variants rather than plan-specific experience.[26] Pennsylvania and Virginia have also implemented premium alignment guidance, and a few other states generally have aligned premiums without published rules providing such guidance.

While a growing number of states are enforcing premium alignment, a majority still passively allow flexibility of rating factors to align rating factors with risk adjustment results. Future alignment of risk adjustment with ACA rating rules might spur rapid changes toward premium alignment, a trend that is already occurring based on objective national measures.[27]

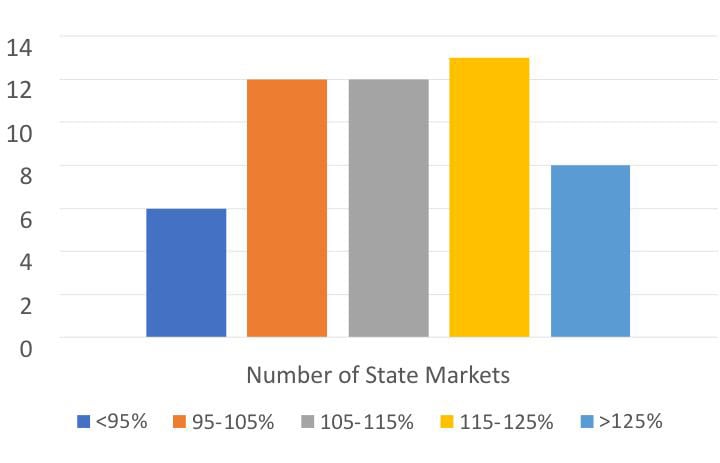

Figure 2 illustrates the 2022 premium relationships of gold and silver plans in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. With CSR defunding, the anticipated gold/silver ratio is about 90 percent, utilizing national silver plan enrollment and published actuarial value and induced demand factors. While associating states with aligned premiums is a complex endeavor, gold/silver ratios are generally a primary indicator. Only six states have ratios below 95 percent. Prior to CSR defunding, successive metal levels were expected to be priced in roughly 20 percent increments. In 2022, 21 states have gold/silver premium relationships above 115 percent, suggesting that the premium relationships in these states are the expected relationships before CSR defunding. In other words, these states may say they allow or prescribe “silver loading,” but the premium rates do not reflect a “load” on anticipated base (70% AV) silver plan premiums. Summarizing, about 6 states have aligned premiums, 21 have premium relationships more in line with the pre-2018 environment, and the remaining states’ premium relationships are between the two end points.

Figure 2

2022 Premium Relationship of Gold and Silver Plans

Risk Adjustment Modifications

A month before President Biden took office, he was offered some advice on fine-tuning ACA marketplaces.[28] The primary suggestion was to “realign metal level premiums.” The authors noted the influence of risk adjustment in this process: “By updating risk-adjustment formulas and encouraging states to enforce basic requirements for setting premiums, federal officials can fix this misalignment and save money for the vast majority of people who are covered through the individual market.” The 2021 HHS Technical Paper examines these risk adjustment updates with particular attention to silver CSR 87 and CSR 94 enrollees; several variations of a proposal to reflect recognition of platinum level liability in the ACA risk adjustment methodology as early as plan year 2024 are discussed.[29]

However, before laying out these proposals, HHS offers quantitative evidence that the agency believes the risk adjustment methodology is working as intended. It cites “a lack of evidence of higher induced demand associated with the receipt of CSRs for most CSR enrollees.” Definitionally, induced demand reflects different behavior associated with different benefits for a similar population. Undoubtedly, silver CSR 87 and CSR 94 enrollees would utilize fewer medical services if they had silver level rather than platinum level benefits. Of course, there is not comparable data as the enrolled population is offered platinum level benefits due to their income and do not have a logical offering of silver level benefits. Nevertheless, this conclusion is reached via a comparison of different populations rather than similar populations with different benefits, likely reflective of cost sharing having a differential impact on populations with different income levels. In fact, this is precisely the commenters’ rationale: “CSR enrollees tend to be more price sensitive due to their lower incomes and are not in fact using more services despite having more generous coverage.”

ACA rating rules simply do not allow the following process of risk segmentation:

- Silver enrollees and platinum enrollees have similar platinum level benefits.

- Platinum enrollees generally elect platinum metal level due to health status.

- Silver enrollees generally elect silver metal level due to income and CSR eligibility.

- Platinum enrollees have high utilization because the population is less healthy.

- Silver enrollees have low utilization because the population is lower income and has a broad health status mix.

- Platinum plans should be priced differently than silver plans due to different population characteristics and plan selection rationale rather than different benefits.

HHS believes the risk adjustment methodology is “predicting what plans are actually paying for CSR enrollees reasonably well” based on “the 70 percent AV of the standard silver plan.” Of course, the rating of silver plans should be based on the plan liability of the mix of silver plans, which is not 70 percent. The risk adjustment transfer formula includes a 12 percent credit for silver CSR 87 and CSR 94, which coincidentally is a rough offset to additional plan liability induced by CSR defunding. This is not evidence of alignment of risk adjustment methodology with ACA rating rules, but rather a convenient matching of unrelated factors. Actuaries have responded that this “matching as a success indicator” is “not the intent of the current formula” and have regarded the dynamic less formally as a “happy accident.”[30]

While noting the belief that “current CSR induced demand factors (IDFs) should be re-evaluated because of a potential lack of alignment between the original intent of the CSR IDFs,” HHS reiterates that the risk adjustment methodology does not result in “meaningful overcompensation of CSR plan variants or under compensation of plans at other metal levels, contrary to concerns of some stakeholders.”[31] This viewpoint is predicated on the use of silver rather than platinum coefficients and does not align with ACA rating rules.

HHS appears to be moving toward alignment with rating rules while maintaining that the current methodology is working as intended. It may indeed be working well in the sense of what it is measuring, but if the methodology is not properly adjusting for the risk resulting from regulatory constraints on premium factors, we cannot rightfully recognize it as risk adjustment. The measurement is not reflective of the bridge between ACA rating rules and actuarially constructed factors absent those rules. It may indeed align with the gap between ACA premiums and premiums with unregulated factors, but that is the natural result of ACA premiums being developed specifically from the results of ACA risk adjustment methodology rather than prescriptive ACA rating rules. The aligning results may appear pretty, elegant and aesthetic, but they are not functional toward the ACA’s design. This is perhaps best illustrated by a hiking trail a few hours from my home. Walking across the “Bridge to Nowhere” does not lead to anything of value, other than beautiful scenery. ACA risk adjustment methodology, which does not properly reflect ACA rating rules, does not bridge the appropriate gap, and we would be wise to recognize that bridge, although beautiful, as a functional bridge to nowhere where health plan actuaries remained tasked with old-world practices of plan level risk assessment and experience rating.

It is also worth noting that the HHS re-evaluation of the “potential lack of alignment between the original intent of the CSR IDFs” may suggest a belief that CSR defunding is creating the resulting inequities in the risk adjustment methodology. If this were true, the risk adjustment methodology would have acted as a reinforcement of ACA rating rules through 2017, and premium alignment issues would have originated in 2018. It should be clarified that while risk adjustment should foster premium alignment with ACA rating rules, the direct responsibility for compliance enforcement is the regulatory rate review process.

HHS also discusses utilizing a “weighted average rating term AV across all plans at the national level, thereby ensuring the AV will be the same amount for all silver plans nationally.”[32] National average enrollment patterns are simply the aggregation of different enrollment patterns in different states, reflecting an unorganized mix of different levels of metal level risk selection being used in each state. The current aggregated enrollment results are meaningless and not reflective of future marketplaces with strengthened premium alignment rules. Risk adjustment methodology should clearly be based on ACA rating rules, not “national average” experience that includes a wild assortment of enrollment patterns resulting from various state deviations from ACA rating rules, as well as state policy distinctions, such as Medicaid expansion.

Actuaries have valuable knowledge to offer policymakers and regulators about risk adjustment modifications to facilitate alignment of ACA premiums, improve consumers’ experience, and “foster the development of markets where health plans compete on quality, efficiency, and value, not on risk selection.”

Two Realities

As premium alignment enforcement increases at the state level, I speak more frequently with health plan actuaries with multi-state responsibilities who live in multiple ACA realities. When risk adjustment methodology is not aligned with rating rules, one of two things happens. In an environment where rating rules are strictly enforced, new-world inequities arise when health plans’ enrollment mix differs among risk characteristics that are constrained by rating rules but not properly accounted for in the risk adjustment methodology.

In an environment where rating rules are not strictly enforced, we are still living in the old world. In that world, health plans are not competing on quality, efficiency and value; they are competing on risk selection and understanding risk adjustment as a crucial input variable to quantify risk assessments. A mechanism that transfers funds between health plans without proper consideration of rating rules is not risk adjustment. It is rather another rating factor that health plans must assess to determine their premium relationships between benefit plans. When asked in 2020 why a benefit plan with a higher actuarial value was cheaper than a benefit plan with a lower actuarial value, a health plan actuary plainly responded, “Our approach incorporates actual experience by metal level in the determination of the utilization adjustment among plans in the Individual marketplace. The experience is reviewed after applying the impact of risk adjustment and reinsurance . . . This approach is consistent with prior years and with other carriers in the market.”[33] This is common practice in many states that have not promulgated specific rating guidance, and it explains how “utilization adjustments” between even bronze and platinum plans are directionally opposite from what benefit-induced behavior would suggest.

Piecemeal state regulatory enforcement will likely continue, but I believe health actuaries should consider what we can do to merge the two realities into one. A shift away from ACA rating rules is a workable solution, but it must be recognized as such. As state promulgation of regulatory guidance to strictly enforce ACA rules disrupt premium relationships in state marketplaces, actuaries cannot maintain that current premium relationships are in alignment with ACA rating rules.

Actuaries have demonstrated the ability to practice in the pre-ACA environment, the ACA environment between 2014 and 2017, and in the current environment with CSR defunding. The situation today represents a dichotomy where some states have aligned premiums and risk adjustment is the final step, while other states have misaligned premiums that incorporate rating factors not specifically allowed by the ACA.

Actuaries practicing in individual health insurance markets obviously need to understand in which environment they are operating and whether their environment is changing. While premium alignment enforcement is occurring at the state level, localized premium alignment issues are generally attributable to financial incentives resulting from the federal risk adjustment formula, not precisely aligning with ACA rating rules and the absence of strict regulatory enforcement. The ideal ACA environment is one where rating rules are enforced, the risk adjustment methodology reinforces the ACA rating rules, and health plans are generally indifferent to the populations they enroll because risk adjustment appropriately adjusts for risk. In the alternative environment, the ACA risk adjustment methodology is effectively not risk adjustment; it is merely a complicated financial mechanism that feeds actuarial rating formulas in the old world, where health plans compete for targeted populations with no regard for the indifference ideal.

As premium misalignment generally results in lower consumer premium subsidies, I am encouraged to see new actuarial interest in how “methods of pricing plan benefits, developing premiums, and paying plans affect health disparities related to access to coverage, coverage affordability, and health outcomes.”[34] With aligned interests toward stronger compliance enforcement, risk adjustment coordination with ACA rating rules, and premium methodology that recognizes consumer equity, we might reach the ideal ACA environment sooner rather than later.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Greg Fann is a consulting actuary at Axene Health Partners, LLC and leads the Individual/Small Group Markets subgroup of the SOA Health Section. Greg can be reached at greg.fann@axenehp.com.