Critical Illness Turns 40!

By Ashlee Borcan and Jennifer Howard

Health Watch, September 2023

In 1967, medical history was made when a team of surgeons performed the world’s first human-to-human heart transplant.[1] The team was led by Christiaan Barnard, and the procedure was performed at Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. While the first patient only lived 18 days, the world of medicine was changed forever.

Christiaan Barnard was assisted during that first surgery by his brother, Marius, who noticed a financial hardship faced by those who were burdened by serious illnesses, such as those who needed transplants.[2] He observed several of his patients who faced financial hardship and began to ideate an innovative insurance product that would provide a material financial benefit, like life insurance, while the insured was still living. This product came to be known as critical illness insurance, and the first policy was issued on August 6, 1983. Within the industry, Marius Barnard is often referred to as the father of critical illness insurance.

While critical illness policies have certainly changed significantly over the last 40 years, Barnard’s vision lives on. There are now variations in the types of critical illness policies that individuals can purchase and variations in how those products are developed. Generally, there are three primary ways to offer critical illness coverage in the United States:

- Agent-sold policies outside of the worksite, typically on an individual product chassis

- Worksite-sold policies offered on an individual chassis

- Worksite-sold policies offered on a group chassis

These three categories are the most common ways insureds obtain coverage, although there are other options such as direct-to-consumer policies and association group coverage. We will discuss each of these options in more detail later.

Critical Illness 101

First, let’s start with a basic description of the coverage. Think of critical illness as paying a lump sum benefit, just like life insurance, but without the part where you must die to get it. If you purchase a $25,000 policy and you are diagnosed with a covered condition, you will receive a check for $25,000. Each covered condition under a critical illness policy is called a benefit “trigger,” and the number of triggers can vary materially from policy to policy, but the most common ones are as follows:

- Heart attack

- Stroke

- Invasive cancer (There are different naming conventions from carrier to carrier.)

- Major organ failure

- End-stage renal disease

These triggers are typically paid in full and referred to as 100 percent benefits, due to the severity of the conditions. It’s also quite common for critical illness policies to cover less serious conditions at a lesser benefit amount, such as 25 percent. The most common of these lesser benefit triggers are:

- Cancer in situ (Again, there are different naming conventions for this category from carrier to carrier.)

- Coronary artery bypass graft, or coronary artery disease

For simplicity, we will focus most of the discussion on these triggers, but it’s worth noting that complex critical illness policies can have 40 or 50 (or more!) available benefit triggers covering a wide range of diagnoses. Additionally, some policies may offer supplemental coverage beyond the initial diagnosis to provide support for individuals who would like a second opinion regarding their diagnosis and treatment, or those who travel away from their local area to seek medical advice. Furthermore, many critical illness policies include a wellness benefit encouraging insureds to perform regular health screenings in order to diagnose disease earlier and hopefully prevent a more serious subsequent illness.

Many of the other features of critical illness policies vary significantly depending on the type of contract, group versus individual chassis and where the policies are sold.

Agent-Sold Individual Policies

Agent-sold individual critical illness policies are contracted directly between the insured and the carrier. Typically, these policies are referred to as “kitchen table” policies because, historically, an agent would come to the customer’s home and describe the coverage, sometimes at the kitchen table. The coverage is typically offered for a wide range of face amounts, anywhere from $10,000 to as much as $1,000,000, though the benefit triggers are relatively fixed. Like life insurance, more generous coverage usually implies more robust underwriting, going from simple questions all the way to full medical underwriting. In the United States, high face amount coverage isn’t particularly popular, but it can be quite common in other countries.

Individual policies generally have a preexisting condition clause to mitigate insurer risk as these contracts are typically guaranteed renewable for life and can be subject to antiselection, particularly in situations where simplified underwriting is used. Preexisting clauses are typically represented by two numbers, such as 6/12, though the contract language is much clearer. Colloquially, 6/12 means that any disease that manifested in the 6 months prior to the contract issuance would be excluded from coverage for the 12 months after contract issuance. Additionally, there may be a number of exclusions, benefit waiting periods or other provisions for mitigating risk.

Individual contracts are typically issue age rated, generally with issue age bands. The morbidity assumptions utilized in pricing are separately determined for each individual benefit trigger and added together for a total morbidity assumption. The morbidity assumptions for the most common benefit triggers are significantly upward sloping by age, and for this reason, issue age rated contracts can have material prefunding of future benefits. When constructing claim costs for critical illness policies, it is vitally important to consider each benefit trigger separately and ensure that the pricing claim costs align with any necessary stipulations within the insurance contract. For example, it is quite common, if using a data source like SEER,[3] that you would need to make adjustments to the SEER data in order to appropriately align the cancer incidence rates with the invasive and in situ benefit trigger definitions.

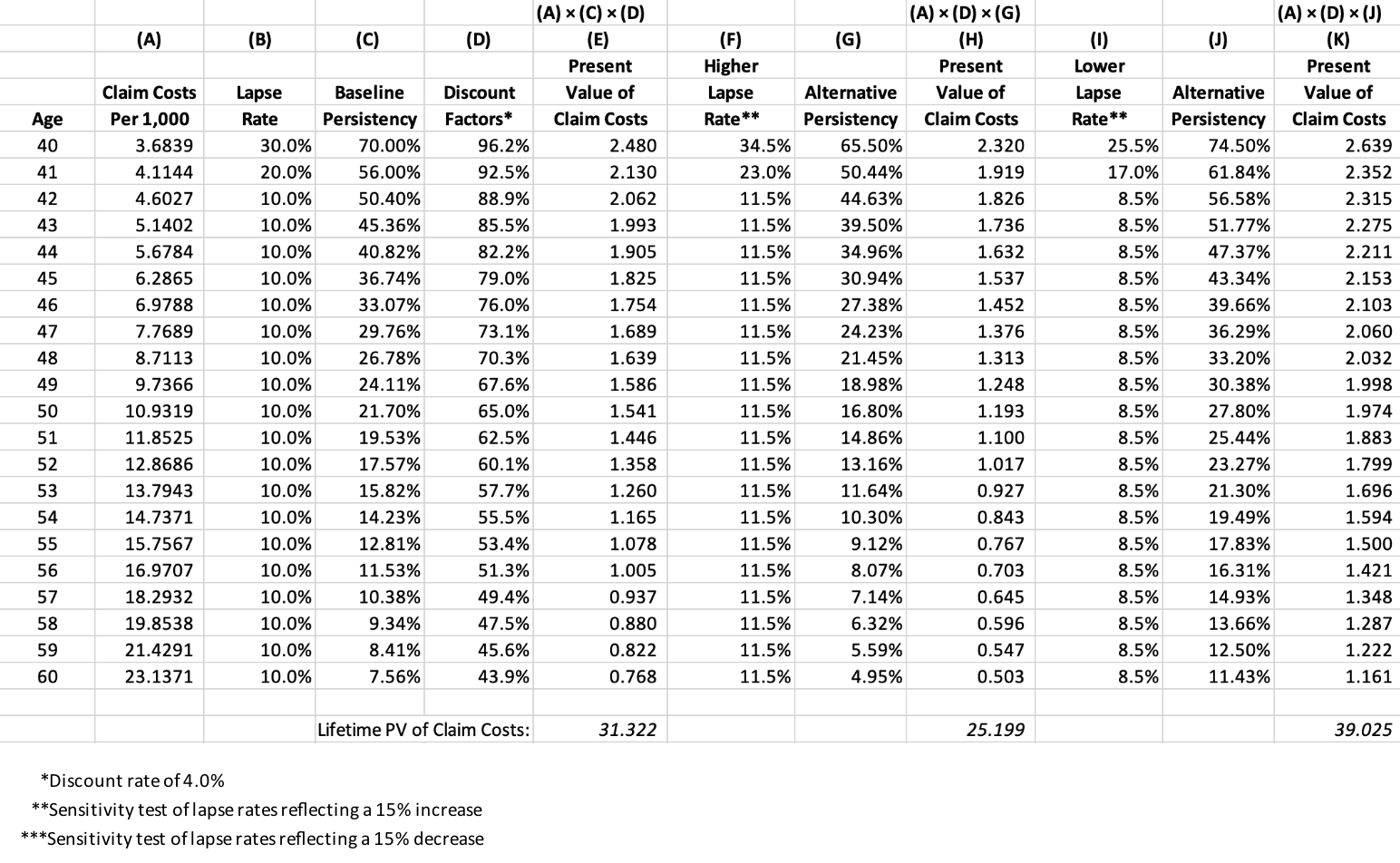

In addition to morbidity, the lapse rates and discount rates are key assumptions that affect the present value calculation of the future anticipated benefit payments. To illustrate the importance of the lapse rate assumption in issue age critical illness pricing, we have assembled the example in Table 1, utilizing a simplified 20-year term critical illness policy and three lapse scenarios: a baseline assumption and a higher and lower sensitivity.

Table 1

Illustration of the Importance of the Lapse Rate Assumption in Issue Age Critical Illness Pricing

Below columns E, H and K, we have calculated the present value of the anticipated claim costs under each of the three lapse scenarios. These values functionally represent the morbidity cost of the coverage and typically directly relate to the premium charged. Individual supplemental health contracts, such as critical illness, are filed with each state, and an actuary must certify that premiums are anticipated to result in a certain lifetime loss ratio (e.g., 60 percent), defined as the present value of future benefits divided by the present value of future premiums.

As can be seen from the example, when policies lapse more quickly, the cost of providing coverage decreases because there are fewer policies inforce in the later higher claim years. Consequently, the opposite is true when policies lapse more slowly. For any actuary pricing critical illness policies, it is important to consider the sensitivity of premium rates to all the assumptions, but lapse rate sensitivity is particularly important.

Additionally, due to prefunding, insurers must hold statutory active life reserves for these policies. The minimum standards for health policies are stipulated by the Valuation Manual and are currently required to be determined on a two-year, full preliminary term basis, with limitations on the voluntary lapse assumptions and where the maximum discount rate permitted is identical to the rate for a whole life policy.[4]

Worksite-Sold Individual Policies

Worksite-sold individual policies are very similar to agent-sold individual policies, with a few key distinctions.

Worksite policies are offered to insureds at their place of work, typically as part of an employee benefits package. The agent may have access to the employee at their workplace, although this method has been greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, as many employees now work part-time or full-time from home. Alternatively, the employee may be educated about the product as part of the open enrollment process for all employee benefits.

Policy sizes tend to be much smaller in the worksite setting. Typical face amounts are less than $50,000, and as a result, minimal individual underwriting is performed. For groups where minimum participation requirements (the number of employees in the population who elect to purchase coverage) are met, there may be no underwriting questions. In these cases, the insurer is relying on the fact that the employee is healthy enough to be actively working, which is considered sufficient underwriting protection. While this philosophy may be convenient for the primary insured, actively at work status is not known for dependents. Fortunately, children are very unlikely to experience a critical illness, so the primary risk lies with the spouse. As a result, it’s quite common to offer reduced coverage to dependents, typically 50 percent. So, if the employee elects $25,000 of coverage, the spouse may only receive $12,500.

Carriers offering coverage in the worksite setting will typically underwrite the group before electing to offer coverage. A carrier will often not offer critical illness coverage to industries with a high risk for exposure to cancer-causing materials (e.g., asbestos) or where high employee turnover is expected.

Critical illness coverage is very different than medical coverage, as these benefits are typically paid directly to the insureds and not to providers and cover a defined benefit trigger. Additionally, there is no burden on the individual to provide proof of medical expenses, as the insured is not required to utilize the benefit to pay medical expenses. These funds can be used for any purpose during a period of illness, including replacement of lost income, childcare, home modifications or other bills.

The lapse rates of worksite-sold policies can be quite different than their individually sold counterparts. Worksite policy premiums are typically paid through payroll deduction. As a result, employees who terminate employment will lose the established mechanism for paying their policy premiums. To retain the coverage, the employee would need to set up a new method of payment, functionally forcing the employee to reevaluate the need for coverage and revalidate the initial purchase. As these policies are typically issue age rated, the longer the insured has the policy, the more expensive a replacement issue age policy would be at a new employer. As a result of this dynamic, there is some additional turbulence in the lapse rates due to employee turnover.

Additionally, it is possible that an employer decides to discontinue offering coverage from one critical illness carrier and instead offer coverage from another carrier. While the employee has not left employment, the employer may elect not to support the payroll deduction of premiums for the initial carrier, and the employee may still be left with the need to establish an alternative payment mechanism. Generally, employers with issue age rated products are less likely to move coverage due to the presence of older issue age policies, but it can certainly happen when a different carrier’s benefits or rate offerings are considered more attractive or in situations where employees complain that servicing from the legacy carrier is poor.

Worksite-Sold Group Policies

While the insured is the policyholder for traditional individual coverage, the group is the policyholder for group coverage and the individual insureds are certificate holders. As an example, if employer A engages with a carrier to issue a group critical illness product, then employer A will be issued the policy. Each employee who elects coverage will receive a certificate that contains key information regarding coverage for the insured. In our discussion, we will focus on employer group coverage, but it should be noted that a variety of groups, such as associations and multiemployer trusts, may elect to offer coverage to their members. Regulatory review of group products may vary by group type, so actions that may be permitted for one group may not be permitted for others.

It's worth noting that the issuance of a group contract is complex. Different carriers have different approaches for what is contained in the policy and what is contained in the certificate. Additionally, while some carriers send individualized certificates to every insured, it is relatively common for generic individual certificates to be provided to the employer, representing the coverage for employees in the group. The individual certificate may be available on the employee portal for reference by insureds as needed. When issuing any type of coverage, whether it be group or individual, it is critically important to ensure that the approach taken is acceptable to a carrier’s compliance, legal and other key teams.

Traditionally, individual contracts are much more regulated by state insurance departments, as individuals are not as knowledgeable as employers about insurance; therefore, some states scrutinize the benefits, restrictions and limitations of coverage. Group policies are assumed to be issued to knowledgeable group policyholders, and therefore states are generally more comfortable with benefits and other flexibility. As a result, group critical illness can be highly variable, even when issued by the same carrier. A single contract may include 50 potential benefit triggers with each one variable, meaning that the carrier can include or exclude the benefit as desired by the group.

This product variability can put enormous strain on the various servicing teams within the carrier. It is a huge administrative lift to set up customized coverage for every group, and therefore, carriers typically restrict customization to larger groups where the premium volume merits additional servicing effort. For smaller groups, it is quite common to offer a set of “shelf plans” to facilitate quick quoting and restrict demand for customization. While the definition of group size varies from carrier to carrier, shelf plans are typically offered for groups below 500 lives, and customization is quite common for 3,000 lives and more. In the middle, there may be a sliding scale of customization depending on a variety of factors, including the attractiveness of the group, the presence of other carrier products in the current benefit offering (e.g., group disability) or overall sales goals.

With a high degree of product variability comes the need for rating variability. While individual products typically have fixed rate sheets for the base product and rider options, group products typically have complex rating manuals maintained by the actuarial teams. It’s quite common to have rating variability developed by the actuarial team for the following flexible benefit features:

- Benefit trigger—including adjustment factors where benefit trigger definitions may be varied and have a rating impact (e.g., the minimum number of days required before a coma qualifies as a critical illness)

- Age

- Gender

- Tobacco status—not applicable to all benefit triggers

- Preexisting condition limitation—often waived for group products

- Waiting period—not common for group products

- Rate guarantee period

- Waiver of premium provision

- Presence of portability—the ability for someone to continue group coverage once they are no longer a member of the group

- Underwriting offering (While most group coverage is guaranteed issue consistent with the individual worksite products, some carriers will perform simplified issue underwriting where employees would like to purchase larger face amounts or if minimum participation requirements for guaranteed issue are not met.)

- Voluntary versus employer paid coverage

- Industry

Additionally, many group contracts have the option of being experienced rated. If a group’s experience is considered credible, the carrier may reflect the experience of the group when rating the group for initial coverage or during renewal. This can be challenging as the group’s experience with another carrier may not be on an apples-to-apples basis with the new coverage being offered. Furthermore, it can take time for the group’s experience to develop sufficiently to be considered credible for rating action. As a result, it is much more common for a group to modify the rating of the entire block of business based on historical experience, as opposed to implementing experience rating on a case-by-case basis.

For smaller groups, the experience may be considered partially credible at best. For example, if a group at renewal is considered 20 percent credible with an actual-to-expected loss ratio of 120 percent, meaning claims were 1.2 times higher than expected, the group may receive a blended renewal rate equal to the following:

Credibility of the group × (Actual-to-expected loss ratio) + (1 – Credibility of the group) × (100%)

= 20% × (120%) + (1 – 20%) × (100%)

= 104%,

meaning the group would get 104 percent of the inforce rate.

Credibility may be assessed based on life years of experience, claim counts (excluding wellness) or some other potential measure of exposure.

Group products also have a rating nuance in that coverage may be provided on an attained age or attained age banded basis. This has a few important impacts:

- Attained age rates by age (where each age has a unique attained age rate and there is no age banding) do not generate prefunding, and therefore statutory reserves are not required.

- Attained age banded rates may generate prefunding depending on the width of the bands and the coverage offered. The actuarial team will need to test the attained age bands to determine if active life reserves are needed.[5]

- As attained age rates do not generate prefunding, employees who leave employment or otherwise lose access to the coverage do not leave behind any residual value.

- As coverage increases in cost every year, or at set intervals, lapse patterns can be different than issue age products.

Many group carriers retain the option to offer coverage on an issue age or issue age-by-age basis as well. Composite rating is not common in the critical illness market due to the increasing slope of claim costs. The exception is when the employer is paying for coverage as the risk for antiselection is significantly mitigated.

Conclusion

This article provides a high-level introduction to the complex world of critical illness coverage. The market has evolved over the last four decades, and recent years have come with several benefit innovations that are likely well beyond what Marius Barnard initially envisioned. We have moved well past the basics of cancer and heart attack coverage to begin to address mental health, infertility and a wide variety of other conditions. The pressure for innovation is high, particularly in the group market, and we look forward to seeing what the future brings.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Ashlee Borcan, FSA, MAAA, is a principal and consulting actuary at Milliman. Ashlee can be reached at ashlee.borcan@milliman.com.

Jennifer Howard, FSA, MAAA, is a principal and consulting actuary at Milliman. Jennifer can be reached at jennifer.howard@milliman.com.