Overcoming Personal Bias in Risk Messaging

By Kat Kapuscinski

The Stepping Stone, January 2023

There are two key challenges one must overcome to gather the best data for managers to make data-driven decisions. One is fundamental to data analysis: consistency in formulas, data groupings, and definitions. The other requires a softer skillset—preventing management’s past experiences from influencing how data is perceived and reported.

Perception Versus Data

In my experience, most operational managers collect memories and use them as if they are based upon factual data. They utilize their past experiences, which are subject to cognitive biases, memories, and personal interpretation. Thus, requests for data and subsequent reporting do not clearly provide the full story.

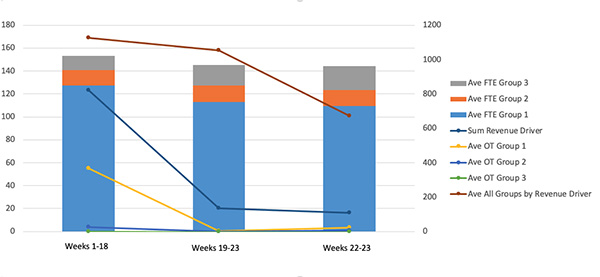

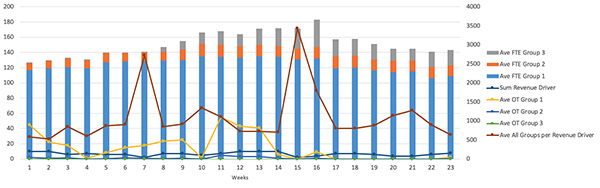

For example, one new manager wanted to present 23 weeks of historical data in three groupings to highlight the immediate impact they made starting at hire: 18 weeks before their hire date, five weeks after their hire date, and a call out of two weeks within the five week period (see Figure 1). In this way, the data showed remarkable improvement within the five week timeframe. However, after looking at the data in individual weeks, it was very apparent the data showed only a minor trend change, with three anomalies grouped into the 18-week spread (see Figure 2).

“If this were played upon a stage now, I could condemn it as an improbable fiction.” -Shakespeare’s The Twelfth Night

Figure 1

Requested Data Grouping to Show Improvement

Figure 2

Data by Week Showing Anomalies

- What is the truth?

- Who is collecting and reporting the data?

- How do we make the best decisions with the information at hand while also remaining aware of human fallibility?

The data itself speaks a story, if collected and reported in an appropriate method which fits the business and the people. Analyzing raw jumbled data requires playing with the groupings, like rearranging a Rubik’s Cube, and asking questions until the story aligns and leaps off the spreadsheets.

Taking It Personally

Early on, I thought I knew how to handle this. After listening to management’s frustrations and focal points, I gathered additional data, rearranged it to compare it to expected experience, and then validated it. I found large gaps between the awareness of facts and management’s comprehension of the business; data speaks truer than management. Wanting to help my fellow teammates, I openly showed where the true gaps existed. The data and I were both met with shock, frustration and full rejection.

How did I respond? Not well at first. I took their negative reactions personally. I asked my boss what I could do better. Her advice was golden:

"Be more personable so they understand who you are and your motivations.”

This feedback shocked me. I am a very caring person. I hadn’t realized that my professional (read: strictly square) demeanor was so different from my own inner personality. Data cannot be served cold. This advice rippled across my life for years, and initiated many life changes. I am indebted to her.

I experienced this same rejection many times, because I believe complete data tells the truth and continue to seek it. Each rejection led me to learn more nuanced ways to approach management and respond to personal reactions. I also learned that my own self-awareness needed a fact checker, too.

How do we collect, monitor and report data to overcome such a nebulous topic as personal perceptions?

Understanding Resistance to Data

Data doesn't exist in a vacuum of truth, fear is an underlying barrier to efficient data collection.

- Decision makers tend to hide their worst fears as a means to show strength.

- Data is not reported accurately nor wholly.

- Data will be ignored.

With as many bosses as years of work experience, I’ve encountered myriad leadership styles. Despite these changes above me, it took me speaking freely about my own self to truly become aware of such a key component in business: the response to data is a personal response. The key to extracting the data and reaching the best conclusions involves understanding the human component and speaking to it.

Differentiating the People

I learned to listen to people. Roles, titles, and responsibility levels don’t matter so much as the person performing them. We all have our own histories, perceptions, weaknesses and strengths. It’s important to listen to each decision maker’s perspective, find the gaps in data, and respond to management in like kind.

In listening to one manager, I learned he liked to proclaim success based upon comparisons to other similar organizations; I presented comparative data to him.

One manager liked to show cost savings. After working with the data analysts, I realized they were working with different definitions, so that their concept of savings conflicted with how we were communicating to leadership. Sitting side by side and working through the formulas and output, we aligned the data analysis to the operational processes and subsequent reporting.

Another manager liked to disparage others and avoid third party authority; I used jokes to create a jovial friction and lighten the mood, and reminded him of laws we were required as a business to enforce.

One new manager wanted to show improvement in injuries for her first 75 days. Before her hire, the company had been pushing for increased attention to safety and near miss reporting following a hiring frenzy. Near miss reporting to accident report ratio was .5:1 before her arrival, and reporting dropped off the following month. During the new manager’s first month, there were more injuries than normal. After asking questions and making sure I clearly understood the request, to only show OSHA recordables, the data showed stagnant counts within that timeframe, which wasn’t worth reporting to the board. In fact, the analysis showed that near miss reporting had decreased significantly, a leading indicator that accidents may increase again.

The most troubling encounter was with a manager who spoke openly about preventing kickbacks, while also setting us up to act with favoritism. This took months of working ethically in a hostile environment until I recognized my only avenue was to escape. Sometimes success isn’t possible. It’s OK to let go and move on.

Bringing it Together

When a decision maker is approached with open and accepting communication in a style that meets their own, it is more likely they will work with risk management, facilitating the creation of solutions. When asked for data, ask questions to ascertain the thought process behind the request, provide a fuller picture than expected, and foster a discussion about the possibilities the data may present to management.

Don’t ignore the rejections, use them to understand the people. Approach and acknowledge the cause, then engage it with personal transparency. “I understand you are (excited/concerned/focused). This is what I’ve been able to find, based upon X/Y/Z.”

Working effectively with others is an ongoing process which will never end, and the data will evolve as we do. We must facilitate open and transparent communication. Keep your chin up, back straight, and head clear.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Kat Kapuscinski, MS ERM, ARM would like to hear from you. She can be reached at kk3346@columbia.edu. LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/kat-kapuscinski-mserm-arm.