Long-Term Care and Actuarial Equivalence

By Robert W. Darnell

Long-Term Care News, June 2021

For many Long-Term Care insurance (LTCi) policies, there have been multiple rounds of rate increases. Policyholders have continued to keep their policies in-force, illustrating their desire to keep their benefits. In the early 2000s, rate increases averaged around 20–50 percent. Over the years, each round of rate increase appears to be larger and larger. Today, a number of single rate increases are 200–400 percent. Cumulative rate increases often exceed 500 percent. At some point, it may be expected that many policyholders will be forced to lower their benefits.

Based on the originally selected benefits, policies have built large contract reserves. The contract reserves are intended to pay for future benefits. Currently, when policyholders lower their benefits, their contract reserve (funded by the policyholders’ prior premiums) decreases, and the policyholders lose access to the contract reserve decrease. The carrier collects the reserve decrease. Because of this, the carrier has a vested interest in the policyholder’s decision regarding lowering benefits. This needs to change; carriers should not have such a vested interest. The following is a suggested approach.

In a discussion regarding Actuarial Equivalence, one should consider that the policyholder pays premiums that fund administration costs, benefits and the contract reserve. The key feature of the contract reserve is that it is used to fund the policyholder’s future policy benefits. At any point in time, the only intent of the contract reserve is to pay for future claims. The contract reserve is never intended to pay for past claims or to be paid to the policyholder as cash.

Two primary points of this discussion:

- Actuarial Equivalence—the point at which the company is indifferent to the decision made by the policyholders.

- Reasonable Value—an alternative solution offering reasonable compensation to the policyholders when a company may not be able to provide Actuarial Equivalence (often due to administrative difficulties). In this case, the company should explain why its intended adjustment provides a Reasonable Value compared to a solution that is Actuarially Equivalent.

Current Contract Reserves Are Adequate

At the time of original pricing, a policy lapse reduces the premium for surviving policyholders due to the release of the contract reserve. At the time of a rate increase, a policyholder may mitigate the rate increase by lowering their future benefits. When this happens, the current contract reserve is lowered. The decrease in reserves is equal to (1) – (2), where

- = current reserve for the initial benefits

- = initial reserve for the new benefits

Since the policyholder paid the premiums to fund the contract reserve, if the reserve is lowered, the difference should continue to be used to fund the policyholder’s future claims. The reserve difference could be used to (1) increase the policyholder’s future benefits or (2) decrease the policyholder’s future premiums.

To be clear, if the benefits are lowered at duration 20, the reserve for the original benefits and the new, lower benefits are both calculated from duration 20, using the initial assumptions.

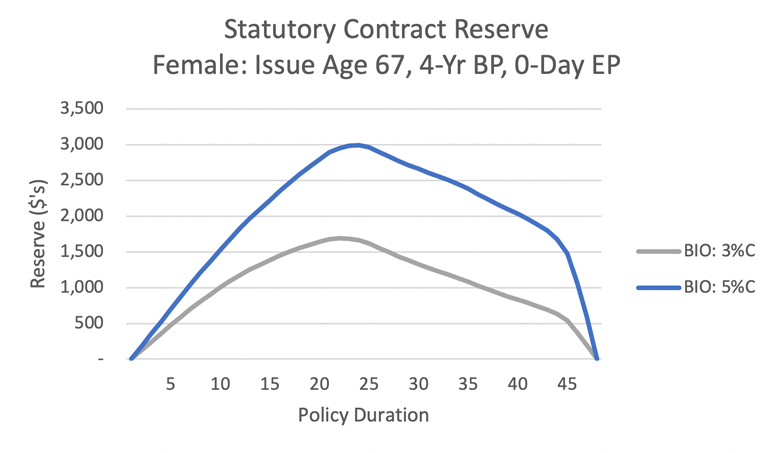

As an example, consider a policy with 5 percent Compound Inflation Protection. When facing a rate increase, the policyholder may elect to reduce the inflation protection benefit to 3 percent compound. Figure 1 shows two sample sets of reserves by duration, one for 5 percent Compound Inflation Protection and another for 3 percent Compound Inflation Protection.

Figure 1

Comparison of Contract Reserves

Landing Spot

The insurance company may offer the policyholder no rate increase if the policyholder will accept a future inflation protection rate that is less than the initial interest rate. Until the new Inflation Protection interest rate is calculated, it is referred to by the generic term “Landing Spot.”

Option 1: Policyholders keep their original benefits. Future benefits are funded by their current reserve and their rate-increased premiums. In calculating the future benefits, the company uses new assumptions and the original Inflation Protection interest rate (often 5 percent).

Option 2: Policyholders keep their original premiums. Future benefits are funded by their current reserve and their non-rate-increased premiums. In calculating the future benefits, the company uses new assumptions and the new Landing Spot interest rate. The Landing Spot must be determined.

To calculate a Landing Spot, insurance companies use four different numbers, all present-valued to the same date (the Valuation Date):

- Premiums with the rate increase

- Premiums without the rate increase

- Incurred claims using the new assumptions and the original Inflation Protection interest rate

- Incurred claims using the new assumptions and the Landing Spot

The Landing Spot is solved when (1) – (2) = (3) – (4). When this happens, the reserves are lowered from a curve similar to the upper curve in Figure 1 to a curve similar to the lower curve (but at the Landing Spot interest rate). Note that (1) on the valuation date, the two reserves curves will be equal; (2) both projected reserves curves are correct because they are based on the new assumptions; and (3) to the extent the current reserves are used and the newly calculated reserves are not used, the difference should be held as a policyholder-funded reserve (i.e., not an Additional Reserve) because it has been used to calculate the new benefit levels.

In the past, the reserve decrease, triggered by the policyholder’s lowered benefits, was not used for the policyholder’s future benefits but instead attributed to the company’s surplus. This situation was not Actuarially Equivalent. The insurance carrier had a vested interest in the policyholder choosing the Landing Spot.

Group Funding

To fund a group of policyholders, Actuarial Equivalence can be defined as the point where the insurance company is indifferent to the decision of a group of policyholders. These options can be considered equivalent when their calculated Future Loss Ratios are equal. The numerator of the Loss Ratio (L/R) is the present value of future incurred claims plus the present value of the annual increase in the contract reserve; the denominator is the present value of the future earned premiums. When these two L/Rs are equal, the two options are Actuarially Equivalent. At this point the carrier does not care which option the policyholders choose. In the past, when the carrier was simply comparing the offset in lowered premiums with the offset in lowered incurred claims, the carrier definitely preferred that the policyholder accept the Landing Spot (because the carrier kept the reserve decrease).

Individual Funding

Group Funding works well for the entire group—ascertaining that the group can decide to go either way on the Inflation Protection interest rate issue, with the carrier being indifferent. Individual Funding works for each individual insured. For example, an individual with a 5 percent Inflation Protection interest rate may want to move to a 3 percent Inflation Protection interest rate. The reserve difference divided by an annuity factor represents the amount to lower the annual premium in future years. With Individual Funding, the carrier is indifferent to each policyholder’s selection. The carrier could calculate the new premium simply by adding a new field to its database for the Annual Premium Discount.

Group Funding vs. Individual Funding

Premium rates are usually calculated by class and filed with each state insurance department on a class basis. However, Actuarial Equivalence includes the contract reserve, and the contract reserve varies by duration. Unless stated in the policy form, class does not include duration.

If Actuarial Equivalence includes the reserve, and premiums are calculated on a class basis that does not include duration, an average (for the class) contract reserve is used for each policyholder for purposes of calculating the decrease in the contract reserves and the subsequent Landing Spot interest rate and/or premium discount. Policyholders with a contract reserve that is lower than the average reserve will “gain” if they choose the alternate solution (e.g., their Landing Spot will be higher). Similarly, policyholders whose contract reserve is higher than average will “lose” if they choose the alternate solution. The combination of all “gains” and “losses” must be considered. If, for the class selecting an alternate solution, the net of all policyholder choices is a gain, this is considered anti-selection for the policyholders in other classes. The total of the “gain” should be lowered so that policyholders in other classes are not impacted.

Actuarial equivalence applies to situations other than just Landing Spots. Co-insurance works very similarly, and the math is a little easier. Actuarial Equivalence also applies to a policyholder reducing benefits other than Inflation Protection.

Commonly, insurance premium rates vary by issue age and benefit options. If rate increases vary by all of these options, funding may come close to Individual Funding. If a rate increase varies by fewer than all of the options, it is clearly Group Funding, and anti-selection may occur.

If the rate increase is complicated (perhaps it varies by issue age, or issue age and benefit period), it may be easier to calculate the reserve difference for each insured. Individual Funding may work better if the carrier already has premium rates for a lower Inflation Protection interest rate. (Individual Funding may not necessarily be for each individual. For the example of the rate increase varying by issue age, the reserve used could be based on the average issue age and the average duration. Similarly, for the rate increase that varies by issue age and benefit period, the carrier could use the average duration for all insureds with the same issue age and benefit period.)

This type of funding could also be done with a change from the 3 percent Inflation Protection interest rate to a new rate at, for example, 1.5 percent (whose premium rates were not available until the time of the rate increase).

This method could be used for any policyholder that wants to lower their benefits—at any time.

Other Concepts

The thought of Actuarial Equivalence instantly brings up the issue of rate increases. Together the two thoughts bring up a number of related issues.

Co-insurance

Another solution to offset a rate increase is co-insurance. This option is similar to the Landing Spot in that co-insurance can be designed to offset the entire rate increase. For the Landing Spot, the policyholder’s premium does not increase because the future Inflation Protection interest rate is decreased. With co-insurance, there is no premium increase because the carrier does not pay the entire Maximum Daily Benefit or the entire Maximum Lifetime Benefit. The co-insurance is usually expressed as a percentage. The policyholder is responsible for the co-pay: the co-insurance percentage multiplied by the original Maximum Daily Benefit. The original Maximum Lifetime Benefit is reduced by the co-insurance percentage multiplied by the original Maximum Lifetime Benefit.

As with the Landing Spot, the current contract reserve and the projection of the current premiums is used to finance the incurred claims less the co-insurance. Also similar to the Landing Spot, the reserves for the current benefits and the reserves for the co-pay option are calculated using the new assumptions. The new contract reserve for the co-insurance option may be higher than the current reserve. If the company continues to hold the original contract reserves, an adjustment should be made because the cost of the new reserves has been paid for by the policyholders.

Reduced Benefit Options (RBOs)

More traditional ways to lower the premium include changing, or perhaps removing, the options selected when the consumer purchased the policy. These usually include reducing the Maximum Lifetime Benefit or the Maximum Daily Benefit, and increasing the Elimination Period. It may include reducing or removing the Assisted Living and Home Care benefits. It can also include any riders and any options for the riders. When any of these benefits are lowered, the contract reserve is usually decreased. To the extent the contract reserve is lowered, Actuarial Equivalence should help to lower the premium for the new lower benefits. At the same time, there is a benefit to the carrier as the reduced benefits should reduce the need for a rate increase.

Insufficient Contract Reserves

If contract reserves are insufficient, the carrier should seek a rate increase for the purpose of increasing contract reserves. If reserve strengthening is considered at the same time that policyholders are offered Landing Spot or co-insurance options, note that the reserves have been recalculated for these two alternatives and the new reserves should be appropriate since they were calculated using the new assumptions. For policyholders not included with the Landing Spot and co-insurance options, it may be simpler to consider the reserve strengthening separately in a rate increase filing.

Additional Reserves (or Premium Deficiency Reserves)

Additional Reserves are usually added because the Gross Premium Valuation (GPV) indicates that contract reserves are too low. These added reserves have not been funded by the policyholders. The carrier has a right to recapture these reserves in a rate increase. The current Additional Reserve could be replaced by a new policyholder-funded “Additional Reserve,” or the contract reserve could be increased. The increased policyholder-funded reserves would then allow the release of the company-funded Additional Reserves to be returned to Surplus. In the case of the Landing Spot, the reserves for the policyholders with the 5 percent Inflation Protection interest rate should have their future reserves increased, due to the calculations based on the new assumptions. Also, policyholders who select the Landing Spot should have the correct reserves due to use of the new assumptions. Similarly, for co-insurance, the reserve for policies with and without co-insurance have new reserves based on the new assumptions.

Again, the Additional Reserves replacement may be simplified if considered as a separate process in a rate increase.

Projections Before and After Policyholder Behavior

Rate increase needs will decrease when the policyholder lowers their future benefits; when the benefits are lowered, the reserve decrease should be included—leading to a lower justified rate increase. Note that the risk decreases when benefits are lowered.

Difference in Actual Policyholder Behavior versus Expected Policyholder Behavior

While a rate increase filing should reflect the expected policyholder behavior due to the rate increase, there will be a difference in projected and actual behavior. Differences will lead to:

- Policyholder behavior leads to more risk than expected—This will lead to another rate increase.

- Policyholder behavior leads to less risk than expected—The extra reserve difference can be set in a fund, accumulated with interest; at the next rate increase, it may be released to lower the rate increase.

Contingent Benefit Upon Lapse (CBUL)

At the time of policy lapse, the CBUL has not been funded by any policyholder; this forces the insureds with CBUL to be included in all future rate increase filings. The remaining premium-paying policyholders pay for the CBUL option. Note that all in-force policyholders have the right to select this option.

Anti-selection

There are several reasons that anti-selection may be expected to be a minor issue for rate increases:

- The majority pay the full rate increase.

- LTCi policyholders are often elderly, with average attained ages above 75 or even 80. Considering how swiftly health can deteriorate in advanced age, they often have little idea what their health will be like in three days, much less three years.

- Some cumulative rate increases have become quite large; it should be expected that more policyholders will downgrade their benefits in order to keep the policy in force. If the policyholder has to downgrade for financial reasons, this is “financial selection” and not “anti-selection.” The downgrade means that the risk was simply lowered for that policyholder. The anti-selection may be due to the policyholders who pay the rate increase, but their reasoning may apply only to the short term.

- Because we don’t yet know the expected claim costs at the highest ages (due to lack of experience), it is difficult to measure either financial selection or anti-selection.

Anti-selection can be a complicated subject for an insured who is 75, 80 or older.

Nonetheless, anti-selection should be considered. Some carriers have offered cash claims. Historically, the cash offers have had low selection rates. With more rate increases, and considering the cumulative impact of those increases, policyholders may become more upset, and carriers will perhaps choose to offer cash more often. Any cash should be less than the contract reserve, perhaps considerably less. The difference in the contract reserve and the cash should be used to cover any anti-selection.

Actuarial Equivalence—When It’s Effective

A final issue is when Actuarial Equivalence should be required. The primary choices are (1) anytime the policyholder reduces their benefits and (2) at any time after an increase in the premium rates or (3) within a limited time period after a rate increase. Option 2 or 3 may be the most sensible. There may be some concern for policyholders who want to pay the increased premium but later realize that they cannot afford the increase and must lower their benefits. Therefore, a period of one year (or one year plus the grace period) after the rate increase may be fair as it makes sure that all policyholders have had a policy anniversary. Allowing Actuarial Equivalence at any time after a rate increase may invite anti-selection.

Rate Increase Filings

These filings should illustrate the impact regarding:

- Policyholder behavior, including the impact of shock lapse and anti-selection

- Actuarial equivalence, including the impact on premiums, statutory reserves and RBOs

Conclusion

Cumulative rate increases for LTCi have become large and appear to be increasing. Policyholders have proven their desire to keep their policies in-force. Due to the magnitude of the rate increases, many policyholders will not be able to continue their current benefit levels. As many policyholders are age 75 or older, their election to lower their benefits may not be anti-selection as much as it is financial selection—they simply can no longer afford the continuing rate increases.

The insurance industry needs to be proactive in finding a solution. Since the policyholder has funded a contract reserve, which may not be necessary if they lower their benefits, a ready solution is to use the reserve decrease to help the policyholder fund their future benefits. After all, the policyholder funded their contract reserve for the purpose of paying future benefits- so why not let them use it? They purchased their policy for the long term, and they have paid their premiums for a long term, so let’s help them keep their policy for the long term.

Spreadsheets are available to assist carriers with the calculations for a Landing Spot and co-insurance. If interested, please contact Bob Darnell.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Robert W. Darnell, ASA, MAAA, is a senior life actuary for the California Department of Insurance. He can be reached at bob.darnell@insurance.ca.gov