Public Pension Risk-Sharing Policies: A Policymaker’s Guidebook

By Don Boyd, Gang Chen and Yimeng Yin

In the Public Interest, March 2021

State and local government pension plans in the United States are predominantly defined benefit (DB) plans. These plans face considerable risks, including investment risk, longevity risk, and inflation risk, with investment risk being the largest. By contrast, in defined contribution (DC) plans, common in the private sector, these risks are borne primarily by the plan member. Many governments have adopted policies, particularly after the Great Recession, that transfer some risks from pension plans and governments to plan members. We think this trend will continue.

To help policymakers and their advisors understand risk sharing we developed Public Pension Risk-Sharing Policies: A Policymaker’s Guidebook, with financial support from Arnold Ventures. In January we released the guidebook and associated fact sheets and Arnold Ventures featured it in a web post.

Public Pension Risk-sharing Policies

The two main ways of sharing risks within the defined benefit structure are making pension benefits variable and making employee contributions variable—in either case, contingent on factors such as investment returns or plan-funded status.[1]

Contingent benefits in the United States usually are implemented by varying Cost of Living Adjustments (COLAs) within a floor and a cap, and generally do not allow benefits to decline from one year to the next. In the Rhode Island Employee Retirement System, some COLAs depend in part on five-year average investment returns. The Arizona Public Safety Personnel plan’s COLA is zero if the funded ratio is less than 70 percent, 2 percent if the plan is at least 90 percent funded, and lesser percentages in between.

Contingent employee contributions can take several forms. The Pennsylvania State Employees’ Retirement System allows some employee contributions to vary depending on plan investment performance. The Connecticut State Employees’ Retirement System requires some employee contributions to reflect a portion of increases in normal cost, depending upon investment performance. The Wisconsin Retirement System shares actuarially determined contributions (ADC) between employer and employee. In a shared-ADC policy, all risks that affect ADCs are shared.

The most important difference between contingent benefit and contribution approaches is who is affected and how: variable benefits affect plan members in their retirement years, and variable employee contributions affect members in their working years. This is a key consideration for policymakers because affected workers may more easily bear risk than retirees who are no longer working. Governments are affected differently, too. If pension benefits vary, liabilities may be lowered, reducing the government’s contribution outlays slowly over many years. If employee contributions vary, current taxpayers’ costs may be reduced immediately.

Triggers have a big impact on which risks are shared: If contingent benefits or employee contributions are triggered by investment performance, then the trigger mechanism only transfers investment risks.[2] If changes are triggered by plan funded status, then all risks affecting plan assets and liabilities are shared.

Contingent benefits and contributions are the most common risk-sharing approach in the United States, but other approaches are possible, such as hybrid plans with defined benefit and defined contribution components, cash-balance plans, and complex policies that combine multiple approaches.

A complex example in the United States is the South Dakota Retirement System, which attempts to keep employer contributions stable while maintaining full funding by varying retiree cost of living adjustments (COLAs) within allowable bounds. If the dual goals of contribution stability and full funding cannot be achieved within COLA limits, policymakers must develop a corrective action plan that may consider many options including benefit cuts. The Wisconsin Retirement System has a complex policy that strives to maintain full funding, coupled with ADC sharing mentioned above.

Many plans in the Netherlands use conditional indexation in which the salary calculation that determines benefits at retirement is affected by risks that occur during working years. In addition, benefits during retirement are adjusted in response to risks that occur during retirement. The calculations to determine whether adjustments are made, and to what extent, are complex and depend upon plan performance relative to funding targets.

Which risk-sharing policies are permissible and practical in a jurisdiction will depend heavily on legal constraints and other institutional factors that vary by state and often by system. In most states, accrued benefits for employees and retirees are protected. Some states also protect benefits to be earned from future service. In many systems, changes to COLAs and contribution rates must be collectively bargained with unions. Another institutional constraint is on the type of plans a system may adopt. If DC plans or hybrid plans are not possible or practical, risk sharing must be done within the defined benefit framework using mechanisms such as contingent COLAs and employee contributions. If current employees’ benefits are protected, risk-sharing policies may only be adopted for new employees.

Whether risk-sharing policies reduce costs immediately or reduce risks of higher costs in the future depends on a plan’s condition when a policy is adopted and on the design of the policy. For example, if a COLA linked to plan funded status is implemented when a plan is underfunded, the COLA may be suspended immediately, reducing employer costs right away. The same risk-sharing COLA implemented when a plan is well funded may reduce the employer’s risk of future cost increases but not reduce costs right away. Several states, including Rhode Island, have implemented risk-sharing policies that immediately reduce benefits for plan members and costs for governmental employers.

Finally, some risk-sharing policies can be affected by choices that employers make or influence, creating potential moral hazard: an employer or plan might purposely change assumptions to trigger risk-sharing with the goal of reducing employer costs. For example, if a COLA depends upon the plan funded ratio, lowering the earnings assumption could reduce the plan funded ratio and trigger a COLA suspension, lowering employer costs.

How Risk-sharing Policies Affect Employer Costs

To analyze risk-sharing policies we extended our stochastic pension model, which can simulate the finances of a pension plan under alternative benefit and funding policies, alternative demographic and actuarial assumptions, and alternative investment return environments. The extended model allows us to examine the cost and volatility of employer and employee contributions, and the value and volatility of member contributions under different risk-sharing policies, in different investment return environments. In this article we focus on the present value of employer contributions, but the full Guidebook examines multiple risk-sharing impacts.

We applied this model to a prototypical public pension plan with average characteristics. We assume the policies apply to all employees from the start; in many states, policies might have to be limited to new employees. In scenarios examined below, the plan initially is 75 percent funded, similar to many public plans today. The results are based on stochastic investment returns drawn from a normal distribution with geometric-mean returns of 7.5 percent and a 12 percent standard deviation. We simulate each policy 2,000 times. The Guidebook also examines risk-sharing policies under a deterministic asset-shock scenario.

We designed a baseline non-risk-sharing policy similar to policies of many public plans. It has a 1.5 percent fixed annual COLA. Employees contribute 5 percent of payroll. The employer pays the remainder of normal cost and amortizes investment gains or losses over 15 years. Investment returns are smoothed over five years.

In the analysis below we compare the baseline policy to eight risk-sharing policies, four that are simple adjustments to defined benefit plans and four that are more-radical departures from the standard DB arrangement.

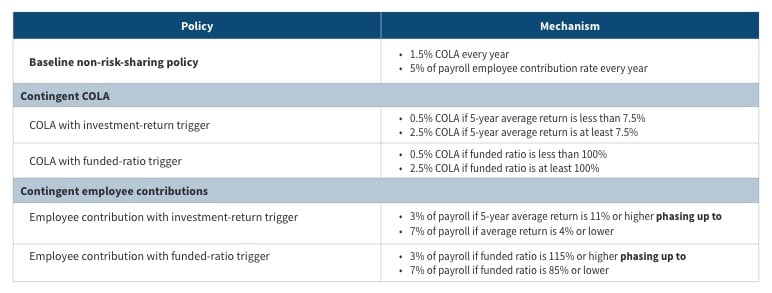

The four simple policies entail contingent COLAs and employee contributions triggered by investment performance or by the plan funded ratio (Table 1). They are styled after policies observed in the United States, calibrated to have approximately the same costs as the baseline policy when plan assumptions are met and the plan is fully funded.

Table 1

Modeled Risk-sharing Policies for DB Plans

The four more-complex policies include two in which the actuarially determined contribution is shared equally between employer and employee; one caps the employee contribution at 10 percent of payroll (a doubling of the 5 percent baseline contribution), and one is uncapped. In addition, we include a DB-DC hybrid plan with employer contributions that are compatible with the baseline, and a conditional indexation policy styled after the Dutch approach. It was not practical to calibrate these policies to the baseline cost; rather, they are less expensive and resemble plans observed elsewhere. (We also examine a policy similar to the South Dakota Retirement System, not shown below.) Full details of these policies are in the Guidebook.

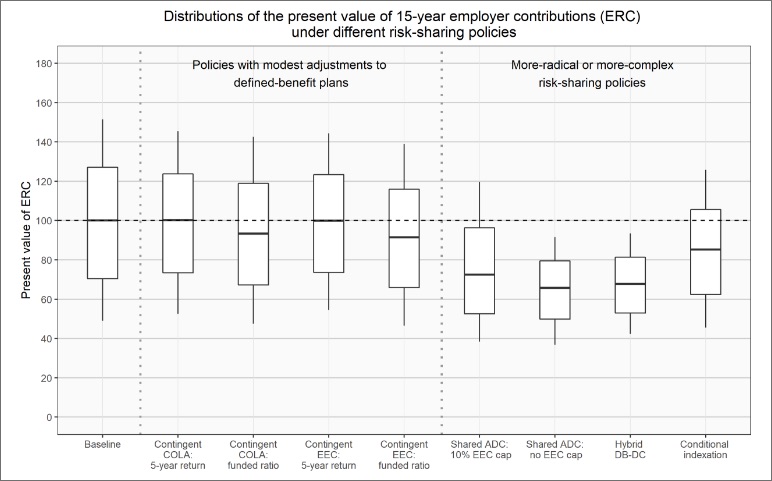

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the present value of employer contributions over a 15-year simulation period under these policies. The top of each box marks the 75th percentile of costs (when returns are bad), the bottom marks the 25th percentile, and the median is the horizontal line. The lines above and below the box extend up to the 90th percentile and down to the 10th percentile. The median cost for the baseline policy is set to 100. The vertical distance from the bottom of the box to the top gives a sense of how much employer costs could vary under the policy.

Figure 1

Employer Costs and Risks Vary Across Policies

The four simple policies, to the immediate right of the baseline, all have lower costs than the baseline when returns are bad—the tops of the boxes and vertical lines are lower. However, the reduction generally is not large in percentage terms. The two simple policies triggered by the funded ratio have lower costs on average than the baseline (the horizontal median line is lower) because as we designed these policies the funded ratio threshold is met immediately due to the 75 percent initial funding of the plan; thus, the COLA is suspended initially. The simple policies would not have large impacts on the range of employer contribution cost—the boxes are of similar size. The key takeaway is that contingent COLA and contribution policies similar to those now observed in the U.S. can reduce employer costs and downside risks, but the reductions are not great.

The four more-complex policies provide far greater employer protection against downside risk and can achieve substantially greater cost reduction, especially the hybrid DB-DC plan and uncapped sharing of actuarially determined contributions. As discussed in the Guidebook, these policies are likely to result in considerably higher contributions or lower benefits for plan members, also.

Conclusions

Risk-sharing policies can transfer some public pension plan risks from governments and taxpayers to plan members. Simple policies within the DB framework, as commonly designed in the United States, can lead to modest reductions in cost and risk to governments. Policymakers seeking significant reductions in cost and risk will need to consider more-radical departures from typical DB arrangements that also entail significant reductions in benefits. We conclude the Guidebook with eight questions for policymakers to consider to help them decide whether and what kinds of risk-sharing policies might be most appropriate in their jurisdiction.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Don Boyd, Ph.D., is co-director with Gang Chen of the State and Local Government Finance Project at the Center for Policy Research at Rockefeller College, University at Albany, and owner of Boyd Research, LLC. He can be contacted at dboyd@albany.edu.

Gang Chen, Ph.D., is an associate professor in Public Administration at University at Albany SUNY. He can be reached at gchen3@albany.edu.

Yimeng Yin, Ph.D. candidate, is an economic researcher at the State and Local Government Finance Project at the Center for Policy Research at Rockefeller College, University at Albany SUNY. He can be reached at yyin@albany.edu.