T3: TAXING TIMES TIDBITS

TAXING TIMES, August 2021

IRS Rules that Retrocession Agreement Qualifies as Reinsurance for Federal Income Tax Purposes

By Maureen Nelson and Rick Gelfond

On March 5, 2021, the IRS released a private letter ruling (PLR 202109005) that provides insight into how the agency analyzes a reinsurance transaction with aggregate risk limits. In doing so, the IRS applied principles for determining whether an arrangement constitutes insurance for tax purposes to reach a conclusion as to whether the subject transaction qualifies for tax purposes as reinsurance.

In the ruling, the IRS analyzed a transaction between a foreign insurance company taxed as a U.S. company by virtue of an election under section 953(d) (“Taxpayer”) and its foreign indirect parent (“Retrocessionaire”). Under the transaction, Taxpayer retroceded risks, originally arising under contracts issued or reinsured by various of Taxpayer’s U.S. affiliates, that satisfied the criteria for treatment as annuity contracts. Taxpayer’s reinsurance of the annuity risks (“Covered Reinsured Risks”) was effected under several modified co-insurance (“Modco”) agreements (collectively, “Covered Modco Agreements”). The retrocession to Retrocessionaire was effected through an agreement (“Retrocession Agreement”), described in more detail below, that transferred the losses of the Covered Reinsured Risks in excess of certain specified limits. Taxpayer asked the IRS to rule that the Retrocession Agreement qualified as reinsurance for federal tax purposes.

The terms of the Retrocession Agreement required the parties to determine quarterly whether the aggregate losses for the year arising under the Covered Modco Agreements were greater or less than the aggregate loss limits specified in the Retrocession Agreement. If they were greater, Retrocessionaire owed a payment to Taxpayer, and if they were less, Taxpayer owed a payment to Retrocessionaire. The Retrocession Agreement was annually renewable unless Taxpayer provided written notice of nonrenewal. Retrocessionaire was entitled, however, to have the Retrocession Agreement renewed if, as of the annual renewal date, the total amounts that Retrocessionaire owed or paid to Taxpayer under the Retrocession Agreement exceeded the amounts that Taxpayer owed or paid to Retrocessionaire.

Taxpayer represented that the formula and risk tranches for ascertaining whether Taxpayer owed Retrocessionaire or vice versa were determined by both an actuarial analysis and a third-party transfer-pricing analysis. Taxpayer also represented that there was a reasonable probability of loss requiring Retrocessionaire to make a payment under the Retrocession Agreement and that this probability was also a factor in determining the payment formula and risk tranches set forth in the Retrocession Agreement.

In responding to the ruling request regarding the tax character of the transaction effected under the Retrocession Agreement, the IRS employed the test it often applies for ascertaining whether an arrangement qualifies as insurance for federal income tax purposes—i.e., whether the arrangement involves insurance risk, risk-shifting, risk-distribution and insurance “in its commonly accepted sense.”[1] In doing so, the IRS first noted that insurance includes the risks taken on by the issuance of annuity contracts.[2] It then stated that risk-shifting exists when one party transfers risk of economic loss to another party so that the transferring party is unaffected by the loss,[3] and risk distribution exists when the insurer pools a large enough collection of unrelated risks. In defining risk distribution, the IRS concluded that the pooling of possible annuity termination dates is risk distribution.[4] It also indicated that in a reinsurance transaction, such risk distribution may be found by looking through the reinsurance agreement to the risks taken on by the ceding insurance company and that risk distribution can be present even if the only business undertaken by a reinsurer involves a contract with a single ceding entity when there is risk distribution at the ceding company level.[5]

Finally, the IRS indicated that insurance in its commonly accepted sense may be found in a transaction that involves, among other things, an adequately capitalized entity organized, operated and regulated as an insurance company, a valid and binding contract with arm’s-length pricing, and a legitimate business purpose.[6] Among the factors identified, the IRS also pointed to, without further explanation, whether an arrangement involved policies that covered “typical insurance risks.”

According to the IRS, because the Covered Reinsured Risks were risks typically found in annuity contracts, insurance risk was present. Because under the Retrocession Agreement, Taxpayer’s losses under the Covered Modco Agreements were mitigated, risk shifting was present. Due to the pooling of the Covered Reinsured Risks, risk distribution by Retrocessionaire existed. And, because (1) Retrocessionaire was adequately capitalized and organized, operated and regulated as an insurance company, (2) the payment formula and risk tranches used to calculate payments under the Retrocession Agreement were determined by both an actuarial analysis and a third-party transfer-pricing analysis, and (3) there was a legitimate business purpose for ceding the Covered Reinsured Risks to Retrocessionaire, the Retrocession Agreement constituted insurance in its commonly accepted sense. Accordingly, the Retrocession Agreement qualified as reinsurance for federal income tax purposes.

This result is not surprising, based on the facts and representations on which the IRS relied. Nonetheless, it is helpful to see IRS analysis in the life insurance space involving a reinsurance transaction with aggregate risk limits, as opposed to seriatim risk sharing.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or Ernst & Young LLP or other members of the global EY organization.

Maureen Nelson is managing director, Tax, FSO - Insurance at Ernst & Young LLP. She can be reached at maureen.nelson@ey.com.

Frederic J. (Rick) Gelfond is principal, Tax, FSO - Insurance, Insurance Products at Ernst & Young LLP. He can be reached at rick.gelfond@ey.com.

Endnotes

[1] In doing so, the IRS cited various captive insurance cases, including AMERCO, Inc. v. Commissioner, 979 F.2d 162 (9th Cir. 1992) and Avrahami v. Commissioner, 149 T.C. 144 (2017).

[2] Citing section 816(a).

[3] Citing Rev. Rul. 2005-40, 2005-2 C.B. 4, and Clougherty Packing Co. v. Commissioner, 811 F.2d 1297 (9th Cir. 1987).

[4] Citing Perano v. Commissioner, 130 T.C. 93 (2008).

[5] Citing Rev. Rul. 2009-26, 2009-3 I.R.B. 366.

[6] Citing Avrahami and R.V.I. Guaranty Co., Ltd. v. Commissioner, 145 T.C. 209 (2015).

Agreement Substituting Related-Party Reinsurers Does Not Give Rise to Base Erosion Payments

By Sandra Lopez P.

On Dec. 4, 2020, the Internal Revenue Service (the “IRS”, the “Service”) published Private Letter Ruling (“PLR”) 202109001 (the “Ruling”).

Main Takeaway

In PLR 202109001, the IRS ruled that a proposed assumption reinsurance transaction between related foreign parties changing the counterparty obligated to a domestic corporation (“Taxpayer”) under an existing agreement did not give rise to Taxpayer being treated as making a base erosion payment (“BEP”), as Taxpayer did not receive a deduction under §832(b)(4)(A) from the amount of gross premiums written on insurance contracts during the taxable year for premiums paid for reinsurance.

Key Facts & Background

In PLR 202109001, Parent (i.e., Taxpayer), and Corp A (both domestic corporations) and foreign corporation (“FC2”) are indirect subsidiaries of foreign corporation (“FC1”). Foreign corporation FC3 is a reinsurance company. FC1 owns a percentage of FC3.

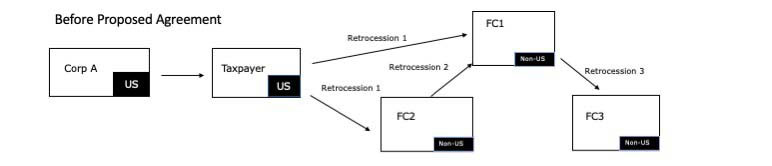

Taxpayer reinsured nonlife risks underwritten by Corp A. Taxpayer then (1) retroceded a portion of these risks to FC1 on a quota-share basis, and (2) entered into another quota-share reinsurance agreement with FC2 under which Taxpayer retroceded to FC2 an additional portion of the risks Taxpayer had assumed from Corp A (both constituting “Retrocession 1”). FC2 then reinsured the risks it had assumed to FC1, under another reinsurance agreement (“Retrocession 2”). FC1 also entered into a reinsurance agreement (“Retrocession 3”) with FC3 under which it reinsured the risks it had assumed under Retrocession 2.[1]

Diagrammatically, these arrangements may be illustrated as follows:

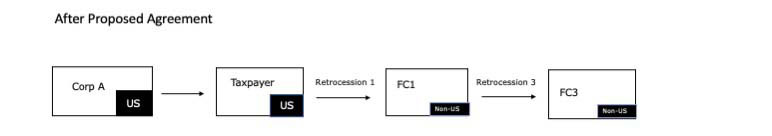

To reduce operational complexity and administrative burden, Taxpayer, FC1 and FC2 propose to enter into an assumption reinsurance agreement (the “Proposed Agreement”). Under the Proposed Agreement, FC1 would be substituted for and replace FC2 as the direct retrocessionaire under Retrocession 1, and FC1 would accept and assume all rights, duties, liabilities and obligations for the indemnity reinsurance. The Proposed Agreement would restructure and replace Retrocession 1, and terminate and replace Retrocession 2. Taxpayer would pay no new consideration as a result of the Proposed Agreement. Taxpayer represented that the obligations in Retrocession 1 and the Proposed Agreement constitute insurance for federal income tax purposes. Taxpayer also represented that Retrocession 1 may be accounted for as prospective insurance.

The changes under the Proposed Agreement may be illustrated as follows:

Issue

The issue was whether the Proposed Agreement affected Taxpayer's liability for purposes of the base erosion anti-abuse tax (“BEAT”) under §59A.

Brief Answer

The IRS ruled that the Proposed Agreement did not affect Taxpayer's liability under §59A. The IRS noted that the Proposed Agreement would operate as an assumption reinsurance transaction within the meaning of Treasury Regulation (“Reg.”) §1.809-5(a)(7)(ii) and, thus, as a sale by the ceding company (FC2) to the reinsuring company (FC1). Taxpayer would therefore not be treated as making a base erosion payment under §59A(d)(3) solely as a result of the Proposed Agreement. However, any amounts paid or accrued by Taxpayer after the effective date of §59A under the reinsurance agreements described above that meet the definition of a base erosion payment under §59A(d) and applicable regulations would still be treated as base erosion payments.

Discussion

The Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (“BEAT”)—Brief Background

The BEAT is essentially a 10 percent[2] minimum tax which may apply to a U.S. corporation or a U.S. branch of a foreign corporation with income that is effectively connected with a U.S. trade or business.[3] The BEAT applies in addition to other taxes imposed under the Code, including the regular corporate income tax and the § 4371 federal excise tax (“FET”).[4]

The BEAT is equal to the amount by which a U.S. corporation’s modi¬fied income tax liability, computed using a 10 percent rate and without taking into account certain deductible base erosion payments and net operating losses (“NOLs”) attributed to such payments, exceeds the U.S. corporation’s regular income tax liability after reduction for certain tax credits.

A base erosion payment is any deductible amount paid or accrued by an applicable taxpayer to a related foreign party.[5] Section 59A(d)(3) specifically includes in the definition of base erosion payments any premium or other consideration for any reinsurance payments.[6]

For further details regarding the impact of BEAT on U.S.-foreign affiliated reinsurance arrangements, please refer to our previous publication, available here.

The IRS’ Line of Reasoning

In PLR 202109001, the IRS found that the Proposed Agreement would operate as an assumption reinsurance transaction within the meaning of Reg. §1.809-5(a)(7)(ii), as FC1 would be substituted for FC2 as the counterparty under Retrocession 1. The Proposed Agreement would effectively operate as a sale by FC2 (i.e., the ceding company) to FC1 (i.e., the reinsuring company). As such, all amounts paid or accrued under the Proposed Agreement would be paid or accrued between FC1 and FC2 (not Taxpayer).

The IRS specifically referenced Treas. Reg. §1.809-5(a)(7)(ii), which defines assumption reinsurance as “an arrangement whereby another person (the reinsurer) becomes solely liable to the policyholders on the contracts transferred by the taxpayer. Such term does not include indemnity reinsurance or reinsurance ceded.” The IRS also cited Beneficial Life Ins. Co. v. Commissioner,[7] which held that an assumption of reinsurance is considered a sale by the ceding company to the reinsuring company.

Moreover, citing Rev. Rul. 82-122, the IRS found that the change in the counterparty obligated to the taxpayer under a contract does not always result in a deemed termination of the contract as regards the taxpayer.[8] In this case, the IRS found that the Proposed Agreement would not result in a deduction for Taxpayer under §832(b)(4)(A) for premiums paid for reinsurance.

The IRS thus concluded that the Proposed Agreement would not affect Taxpayer's BEAT liability under §59A, and specifically that Taxpayer would not be treated as making a base erosion payment under §59A(d)(3) solely as a result of the Proposed Agreement.

Key Tax Considerations

- Payments such as reinsurance premiums typically paid by a U.S. ceding company to a foreign related reinsurance company are generally subject to BEAT. As indicated in this PLR, amounts paid or accrued by Taxpayer to FC1 and FC2 under the reinsurance agreements will remain base erosion payments if they meet the definition of the term under §59A(d) and associated regulations.

- We note that in this PLR, the IRS does not elaborate on the types of payments or deemed payments that may potentially be subject to BEAT.

- Finally, we note that a PLR is directed only to the taxpayer requesting it and may not be used or cited as precedent by other taxpayers.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Jean Baxley for her valuable comments and substantial contributions. All errors remain those of the author. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and may not reflect the official position of Deloitte Tax LLP, its subsidiaries or affiliates.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries or the respective authors’ employers.

Sandra Lopez P., Taxation LL.M. (Georgetown University Law Center), International Taxation LL.M. (Panthéon-Sorbonne University – Paris I), is a senior tax consultant at the Deloitte Tax LLP Financial Services Group in New York City. She can be reached at sandrlopez@deloitte.com.

Endnotes

[1] All the above Retrocession Agreements were done on a “funds withheld” basis (i.e., allowed the ceding party to withhold assets equal to the statutory reserves that otherwise would have been paid to the reinsurer as reinsurance premiums).

[2] §59A(b); Reg. §1.59A-5(b)(2). For taxable years beginning in calendar year 2018, the BEAT rate was set at 5 percent; for taxable years beginning after Dec. 31, 2018 and before Jan. 1, 2026, the BEAT rate is 10 percent; for taxable years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025, the BEAT rate is set to rise to 12.5 percent. See §59A(b)(1)(A), §59A(b)(2)(A); Reg. §1.59A-5(c)(1).

[3] §59A, §882; See Pub. L. No. 115-97, §14401.

[4] §59A(a).

[5] §59A(d).

[6] See Reg. §1.59A-2(d)(4); Reg. §1.59A-3(b)(1)(iii).

[7] 79 T.C. 627, 645 (1982), nonacq. on other grounds, 1984-2 C.B. 1.

[8] See e.g., Rev. Rul. 82-122, 1982-1 C.B. 80.