Mexico: Rocky Road to Recovery

By Daniel Zaga, Alessandra Ortiz and Jesus Leal Trujillo

International News, March 2021

Editor’s Note: This article original appeared, with minor differences, in Deloitte Insights.

COVID-19 deepened the contraction of the Mexican economy. As manufacturing and consumption bounce back, sustained demand for services can help recovery. But a policy push is needed.

The global pandemic came at a time when the Mexican economy had contracted for five straight quarters due to a variety of factors such as deceleration in investment and private consumption and uncertainty around the free trade agreement with the United States and Canada.

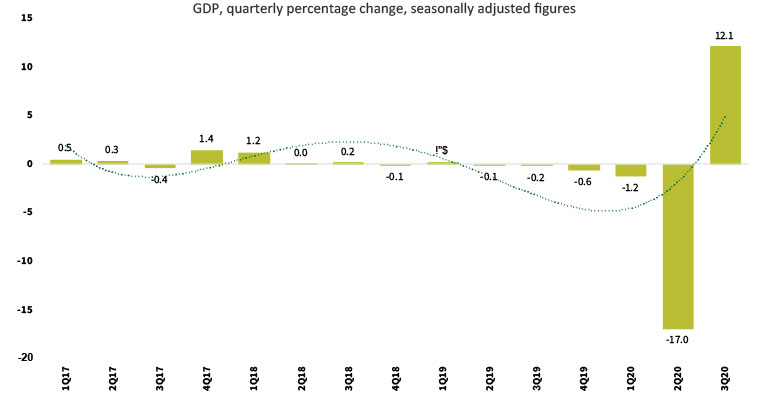

The COVID-19 crisis accelerated this trend, resulting in the largest contraction since the Great Depression of 1929. The forecast for GDP growth this year is -9.0% annually. The economy saw a steep decline of 17.0% from the first quarter to the second, followed by a partial recovery of 12.1% in the third quarter (figure 1). However, the output level is still 8.6% lower than the previous year.

Figure 1

Mexican Economy Contracted 17.0% in Q2—Reflecting the Impact of the Pandemic

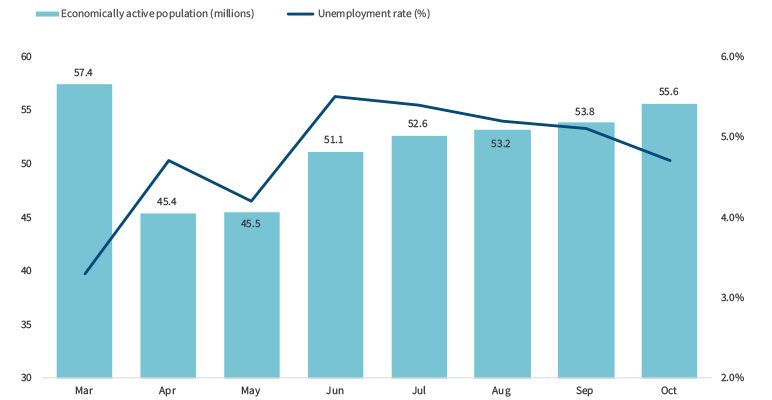

The pandemic has also had a substantial effect on the Mexican labor market. Between April and May this year, 12.5 million people left the labor force and unemployment rose to 4.5%, up from 3.3% in March. The pandemic shrunk the size of the economically active population from 60.5% in February to 47.5% in April.[1] By now, partial recovery of the Mexican economy has helped bring 10.2 million back to work while nearly 2.3 million workers have yet to return (figure 2).

Nevertheless, there are other factors to consider. The vast majority of those who are reintegrating with the labor force are joining the informal market. Besides, the number of people working part-time hours had doubled to 15.7% in October compared to 7.5% in January. This exemplifies how, despite the recovery, working conditions have become more precarious in the country.

The sharp fall in the economy observed this year will have a smaller carry-forward effect in 2021—a year the world will be excited to see the arrival of COVID-19 vaccines, but also one that faces great challenges. Above all, due to the lack of fiscal support and the resurgence of COVID-19 cases, which will affect production and employment once again, the road to recovery will be fraught with uncertainty.

Figure 2

A Huge Chunk of the Working-Age Population Remains Outside the Workforce

Manufacturing and Services: Diverging Paths to Recovery

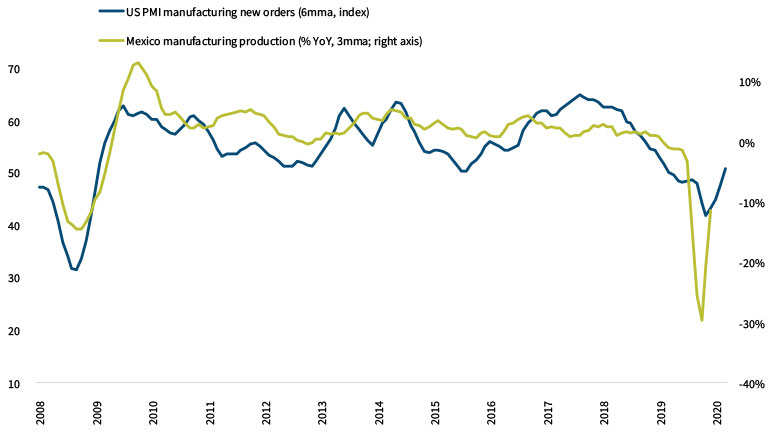

Manufacturing, one of the main drivers of growth in the past decade, registered a significant decline in output as the restrictions imposed due to the pandemic curtailed demand, both at home and abroad. Additionally, the lockdown also reduced output across industries such as automotive and electronics, among others.[2] In the automotive industry, for example, production of cars went from 320,000 units in January to only 3,000 units in April—a fall of almost 100%. However, by October, automobile production had reached 347,000 units.[3]

The gradual reopening of the economy and normalization of trade flows between the United States and Mexico have helped a faster recovery in manufacturing compared to the rest of the economy (figure 3). As economic activity picked up pace in the United States, so did the manufacturing output of Mexico (especially the automotive sector), with many industries reaching their pre-pandemic production levels.

Figure 3

Manufacturing Activity is Recovering Due to Normalization of Trade With the United States

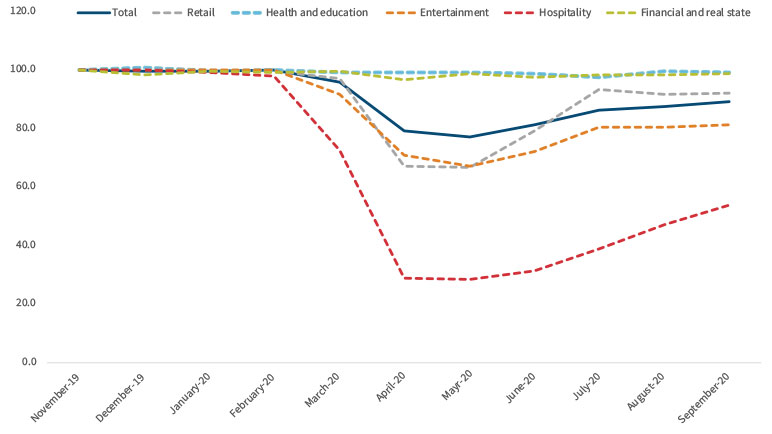

The tertiary sector has been one of the most affected parts of the Mexican economy, seeing a wide variation in performance across activities (figure 4). Financial and real estate services, professional services, education and health care, and government services have been the most resilient. In the harshest months of the pandemic, their decline was around 1.7% year-on-year on average, while in September, it was almost steady on average. Wholesale and retail trade and transportation services rebounded rapidly from a -26.5% decline annually in April to -10.3% in September. Leisure and hotel activities have been the most vulnerable, remaining 32% below September 2019 levels; this sector will take a long time to return to the prepandemic levels (and not only in Mexico). This poor performance has mainly affected some states, such as Baja California Sur and Quintana Roo, which are very dependent on this sector.

Figure 4

Manufacturing Activity is Recovering Due to Normalization of Trade with the United States

This context helps explain why the greatest job losses occurred in the tertiary sector. In October, this sector employed 61.5% of the population, compared to 63.7% in March. Meanwhile, industrial activities saw the opposite effect—the current participation rate is 25.3% against 23.3% registered in March.

Consumption Picking up Slowly due to E-commerce Push

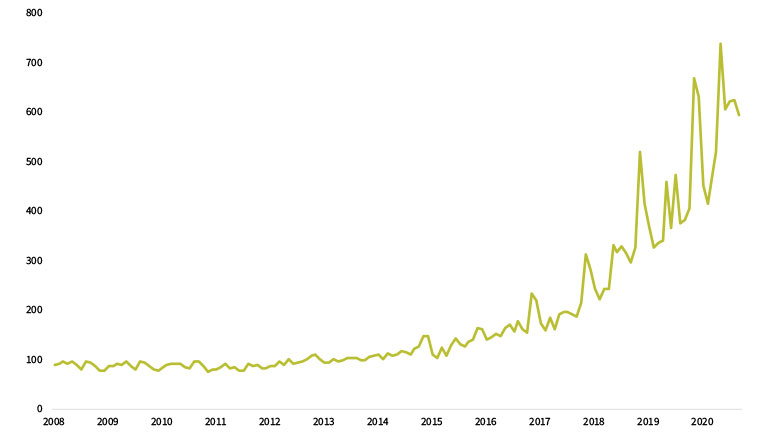

The emergence of COVID-19 accelerated the adoption of online shopping in Mexico (figure 5). According to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), e-commerce sales grew 53% annually in April, 61% in May, 65% in June, 31% in July, 66% in August, and 56% in September.[4] Last-mile delivery of goods increased 212% in September 2020 compared to January levels.[5] In addition, consumers made greater use of the internet to find where to buy products and services. In April, 40% of consumers used digital platforms to conduct online searches, while by October the number had increased to 48%.[6]

Figure 5

The Reactivation Will Come Hand in Hand with Online Business

The pandemic has forced both companies and people to embrace the digital economy. This is good news for the country, as it has been lagging in digitalization. In 2016, only 1.6% of the total purchases made in Mexico were through the internet; in 2019, this percentage had increased to just 3.0%. In 2020, however, the scenario completely changed. According to the Mexican Association of Online Sales (AMVO), between April and June this year, the use of shopping applications increased 90% compared to the same period of 2019. The AMVO said five out of 10 companies in Mexico are doubling their online presence and two out of 10 are registering greater than 300% growth in online sales volumes.[7]

The pandemic has forced both companies and people to embrace the digital economy. This is good news for the country, as it has been lagging in digitalization. In 2016, only 1.6% of the total purchases made in Mexico were through the internet; in 2019, this percentage had increased to just 3.0%. In 2020, however, the scenario completely changed. According to the Mexican Association of Online Sales (AMVO), between April and June this year, the use of shopping applications increased 90% compared to the same period of 2019. The AMVO said five out of 10 companies in Mexico are doubling their online presence and two out of 10 are registering greater than 300% growth in online sales volumes.[7]

Consumption has also started seeing a partial recovery. Data for the first week of November from the Deloitte State of the Consumer Tracker shows consumers’ anxiety around making payments on time is at its lowest level since Deloitte started to track this information. In the first week of May, 61% of responders indicated they had concerns about their capability to make payments on time; in the first week of November, this number stood at 54%. When asked about large purchases, 47% of respondents said in November first week that they were considering delaying big buys, down from a high of 54% in May last week.

The Road to Recovery

The recovery of the Mexican economy will require that the external demand for goods continues at its current rate and the demand for services, particularly tourism, makes a comeback, as this sector alone accounts for 77% of exports of services.[8] The new US government and the country’s plans to increase infrastructure expenditure, along with the global promise of a COVID-19 vaccine, should bolster demand for manufactured goods, thus helping Mexico’s export-oriented industries.[9] Additionally, a more favorable economic environment in the United States will likely result in higher remittances.

Recovery also needs a strong domestic rebound. The federal government has no plans to approve additional fiscal stimulus to benefit the economy, thus limiting the extent of the recuperation of employment and constraining a bolder recovery in consumer spending. As a result, a series of medium-term policies aimed at increasing productivity are necessary to accelerate economic growth.

So far in 2020, the federal government has used 119 billion pesos (US$5.4 billion) of the Budgetary Income Stabilization Fund (the Spanish acronym is FEIP), due to the drop in public revenues.[10] This means that till September, 75% of the total FEIP resources were used; the rest is expected to be spent in the last months of 2020. The budget proposal for 2021 pushes for further austerity and does not contemplate new taxes, despite the slump in revenue caused by the coronavirus crisis and the uncertain outlook for next year’s growth. The income assumptions are based on stricter tax collection and the passage of a bill to eliminate 109 stabilization funds worth 68 billion pesos (US$3.2 billion).[11]

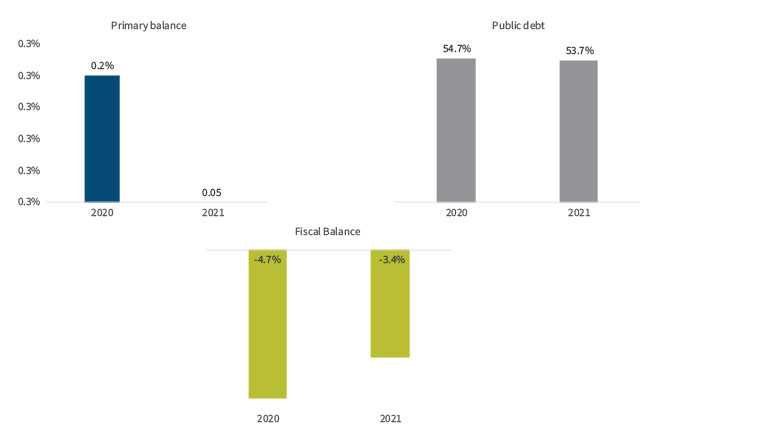

These funds would be a relief to tight public accounts and may help achieve the public administration’s goal of reaching a zero-primary balance in 2021 (figure 6). The “risk”—emphasized by all credit rating agencies—would appear if these “extraordinary revenues” dried up. This leads to the question of when the government will enact a deep tax reform on companies, increase debt to obtain more funds, or redistribute funds from the oil sector. In addition, the finance ministry’s projection for GDP growth (+4.6%) is very optimistic, which will render the government’s targets unfeasible.

Figure 6

For 2021, the Fiscal Targets Seem Very Optimistic

Based on all these factors, we expect the Mexican economy to rebound 3.7% in 2021, after a sharp drop of around 9.0% in 2020.[12] However, the path ahead is difficult. In coming months, there will be further complications in the recovery as there have been spikes in COVID-19 infections in various states and the situation could quickly worsen with the onset of winter. This will result in new tightening sanitary measures (already implemented in some states), which could bring about reduction in economic activity and limit the 2021 recovery.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Daniel Zaga is the economic analysis director of Deloitte Spanish-LATAM. He can be reached at dzaga@deloittemx.com.

Alessandra Ortiz is a senior economist at Deloitte Mexico. She can be reached at alesortiz@deloittemx.com.

Jesus Leal Trujillo is a data scientist for Deloitte Research and Insights. He can be reached at jlealtrujillo@deloitte.com.