7702A Reduction in Benefits Testing: A Simplified Approach

Part 2: Reductions in Qualified Additional Benefits

By Larry Hersh

TAXING TIMES, June 2022

Editors’ Note: This is part 2 of a two-part series. “Part 1: Reductions in Death Benefits” was published in the March 2022 issue of TAXING TIMES.

Overview

In 1988, Section 7702A was added to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986.[1] A policy that qualifies as life insurance under Section 7702 may be classified as a Modified Endowment Contract (MEC) under Section 7702A if the premium payments received under the contract fail the Seven-Pay test. A MEC contract continues to receive favorable tax treatment for the death benefit, but distributions are taxed on an income-first basis and may be subject to a 10 percent penalty.

Section 7702A(c) provides detailed computational rules, including rules that apply when there is a Reduction In Benefits[2] (RIB) under the contract within the first seven years of contract issue or following a material change.[3] For survivorship contracts, the RIB period is extended and applies over the lifetime of the contract.[4]

If a policy has an RIB that is subject to RIB testing under Section 7702A(c)(2), the policy is retested for MEC status retroactively to the start of the Seven-Pay testing period using a Seven-Pay Premium that is reflective of the reduced benefits. The process can be thought of as three separate steps.

Step 1. Determination of MEC Status: In this step, a determination is made that a premium or premiums would exceed a Seven-Pay limit reflecting the lower benefits.

Step 2. MEC Re-compliance: This is the determination if the policy can be brought back into compliance with the Seven-Pay test under the 60-day rule of Section 7702A(e)(1)(B).[5]

Step 3. Non-MEC Testing Limits: If the RIB is determined to not result in the policy becoming a MEC, then the insurer computes the reduced Seven-Pay limit and uses this limit to test against future premiums to monitor for MEC status on a going-forward basis.

In the Part 1 of this series,[6] two methods for providing RIB testing due to the reduction in the death benefit under the policy were provided:

- A “traditional method,” where the Seven-Pay limit is calculated following the reduction, and a retroactive test of the premiums paid is performed against the lowered Seven-Pay test to determine if the policy is classified as a MEC.

- An “alternative method,” where the comparison of the reduced death benefits to a calculated Reduction in Benefit Face (RIBFace) is used to determine MEC status.

These two methods provide identical results. The difference between the methods resides in data that is used to perform the test. Under the traditional method, the policy’s full premium history is used to determine the MEC status by performing a retroactive test of those premiums to the reduced limit. Having the full data available provides for all three of the steps— determination of a MEC status, a determination of the premium(s) that must be refunded to the policy owner to bring the policy back into compliance, and the reduced limits to monitor the policy going forward if it is not a MEC.

Under the alternative method, the policy’s full premium history is not required as the test is not performed retroactively. In summary, the alternative method instead relies upon the cumulative premiums paid to-date, by converting this amount into a minimum Seven-Pay death benefit that would not create a MEC status. If the policy is a MEC, it is possible to determine if the policy could be brought back into compliance. If the policy can be re-complied, the historical premium data would be required to determine the premium refund to be provided to the owner.

Both methods are valuable to an insurer in monitoring their policies. The alternative method provides for an advantage insofar as it requires less data to perform the test. This method may therefore be “another tool in the toolbox” that insurers may be able to use in their Seven-Pay practices.

In Part 2, the alternative method will be expanded to include Qualified Additional Benefits (QAB).[7] A QAB is defined in the Code as an additional benefit that is one of five types: guaranteed insurability, accidental death or disability, family term coverage, disability waiver benefit, or any other benefit prescribed under regulations (to date, no such other benefits exist). If a policy has one or more QABs, then each is allowed to be included in the computation of the Seven-Pay Premium based on the charges for that benefit.[8] Companies will include or exclude QABs from their calculations of the Seven-Pay Premium based on the nature of the benefits, the charges and the length of time that the QAB is on the policy.

Basic Formulas and Assumptions Used

The following formulas and assumptions were used in Part 1 of this series. These are now adapted to include QABs as part of the formulas.

Under both the traditional and alternative method, the insurer must have the following data in order to administer the RIB Test:

- The ability to detect an RIB event.

- The present values of the benefits used as of the Seven-Pay test start date.

- The presence of a Section 1035 premium[9] or other amount spread in the Seven-Pay Premium upon a material change. The term Tax Cash Value (TCV) will be used for this purpose.

- The sum of premiums less nontaxable withdrawals used in conducting the Seven-Pay test.

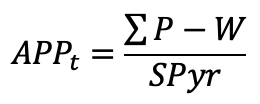

Equation 1: Average Premium Paid

For the alternative method, the Average Premium Paid (APP) is determined at the time of each premium payment (or withdrawal) during the Seven-Pay testing period.

APP uses the “amount paid” as defined in section 7702A(e)(1)(A),[10] which is generally equal to the sum of the gross premiums paid (P) less non-taxable withdrawals (W). However, in defining APP for use in the RIB test, the amount paid at any point in time is divided by the Seven-Pay testing year (SPyr) thus creating an annualized average payment over the testing period. So, at each point (t) where a premium is paid, or a withdrawal taken, the APP can be determined as follows:

The APP described here is the same as was defined in Part 1 of this series. The APP can either be stored on the system, or calculated directly at any time that a financial transaction is processed that results in a change the amount paid, just as would be done for the Seven-Pay test.

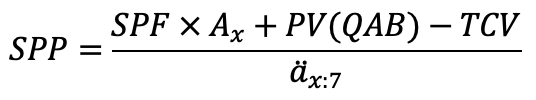

Equation 2: Seven-Pay Premium Formula, including QAB

This formula is provided to help define the terms that will be used throughout this article:

Where:

- SPP = Seven-Pay Premium

- SPF = Assumed Seven-Pay Face Amount

- PV(QAB) = the sum of the present values of each QAB’s charges under the policy[11]

- TCV = Tax Cash Value (i.e., the “roll over” cash value for policies issued pursuant to a Section 1035 exchange, or the cash value used in the calculation of the SPP for a materially changed contract)

- Ax = Net single premium for $1 of death benefit calculated as part of the Seven-Pay Premium determination.

- äx:7= Annuity factor assuming $1 payable at the beginning of each year of the Seven-Pay testing period.

Equation 3: Present Value of Benefits Formulation

This formula is useful when comparing the effects of a change in the death benefit or QAB. It is simply the actuarial equation that equates the present value of benefits to the present value of premiums plus the policy’s TCV.

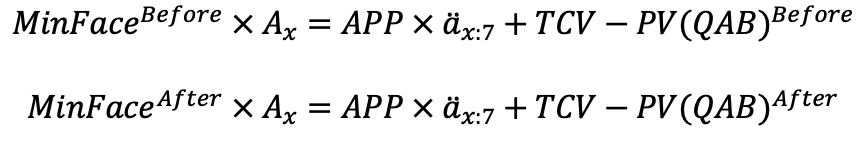

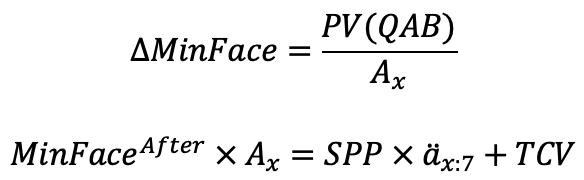

Equation 4: Minimum Face Amount for a Given Premium and QAB

When there are no QABs under a given policy, the minimum non-MEC death benefit (MinFace) can be solved for directly from the premium. Each time the APP is changed by the payment of a premium, the MinFace amount may be recalculated directly.

When one or more QABs are present under the policy, then the MinFace is recalculated upon either a change in the APP or when there is a change in the QABs.

Equation 5: Reduction in Benefit Face Amount (RIBFace)

At any point in time where there is an adjustment made to the MinFace for either a premium or change in QABs, the RIBFace is recalculated as the higher of the amount before or after the adjustment:

The RIBFace is used only for purposes of measuring the policy’s death benefits to determine if the policy would be a MEC during an RIB Test. If the death benefit is less than the RIBFace, then the policy would be a MEC at some point during the Seven-Pay testing period. This process will be explained further.

Step 1: MEC Determination with QABs

The inclusion of one or more QABs under a policy add significant complexity to RIB testing for several reasons:

- As these are optional benefits, they may or may not be present on a given policy. If a policy has reductions in both death benefit and QAB, it can be difficult to see which reduction caused the policy to become a MEC.

- The benefits take different forms—family term, disability benefit, guaranteed insurability and accidental death or disability.

- The Seven-Pay calculations must consider the rider charges, and not their benefits directly.

- Some benefits may be scalable (e.g., family term may use a face amount) and others may not (e.g., guaranteed insurability).

All of these considerations make the administration of a QAB potentially more difficult than the death benefit in the Seven-Pay test, including reduction retesting.

Under the traditional method, the calculation of the reduced SPP and associated RIB Testing is done reflecting the combined effect of any reduction in both the death benefit and any QAB. The premiums are tested against this reduced Seven-Pay limit and a MEC determination is made.

There is a limitation in the traditional method. If the contract contains language that states that a reduction is not processed without policyholder approval if the policy would become a MEC, then the reduction transaction is not processed under the terms of the contract. However, the owner may ask what level of benefits is allowable. Under the traditional method it is not clear what the combined level of acceptable benefits may be without some trial and error.

At first glance, the same problem exists under the alternative method when a QAB is present. Under Equation 3, what is present is the classic mathematical problem of having “one equation and two unknowns”; that is, one set of aggregated premiums but multiple benefits present

A mechanical approach is therefore required. Using the idea that the QAB are additional benefits, the method presents itself as follows:

- Solve for the QAB First: Solve for the MinFace and RIBFace assuming the reduced QAB benefits.

- Check the death benefit (before any reductions in the death benefit are reflected) against the new RIBFace and if lower mark the policy as a MEC accordingly. If the policy is a MEC, it is due to the reduction in the QAB.

- If not a MEC, then any reduction in the death benefit can be tested to determine if the applicable reduction in death benefits would cause the policy to become a MEC.

Note that it is possible to do this process for each benefit reduction separately. The ability to decompose the RIB test by each benefit present will be discussed in more detail below.

Minimum Face Amount for a Change in QAB

In Part 1, it was assumed (for both the traditional and alternative methods) that the insurer could detect an RIB event, calculate the present values of the benefits and track the premiums for use in the Seven-Pay test. With the addition of QABs the same assumptions apply as before with one additional comment. The system must also be able to separately solve for each of the present value of the QAB’s charges on the policy. To demonstrate the method we only need consider a policy with one QAB present.

A reduction in QABs can be best shown by using Equation 3 (present value of benefits and premiums). In this case the APP and TCV are constant. Then solve for the PV(QAB) before and after the reduction.

To solve for the MinFace, we use Equation 3:

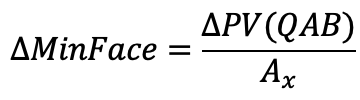

The increase in the MinFace can therefore be quantified by the following amount, as shown in Equation 6.

Equation 6: Contribution of a QAB to the minimum non-MEC Face Amount

The increase in the MinFace is the amount of the PV(QAB) charges that are no longer applied, grossed up by the net single premium as follows:

What Equation 6 provides is an implied “cost” of each QAB that is being reduced. In this context the term cost infers a limitation on the reduction in the death benefits allowed based on the change in the QABs present under the policy. The reduction in the QAB increases the minimum face. Assuming the policy is not a MEC, then any reduction in the death benefit would be limited by this newer, higher MinFace (and RIBFace). This reflects the fact that the Seven-Pay test reflects the total premiums paid for both types of benefits against a single Seven-Pay limit.

As a result, the effect of a reduction in multiple benefits can be decomposed into a set of implied costs for each QAB that is reduced by using this process:

- For each QAB that is to be reduced, calculate the contribution to the MinFace effect using Equation 6.

- The new MinFace is the MinFace before any QAB reduction, plus the incremental additions to MinFace for the QAB’s that have been reduced.

- The RIBFace amount is then reset in the same manner as before in Equation 5. It is the greater of the existing RIBFace or the new MinFace.

- If the policy’s death benefit is less than the RIBFace amount, then the policy became a MEC because of the reduction in the QABs.

- After all QABs are tested, an applicable reduction in the death benefit can be separately tested. Note that the RIBFace for this purpose is not re-computed, as it would already reflect all changes in the QABs and APP amounts.

Having each benefit tested in such a manner provides information that may be valuable to the policy owner. Being able to separately see the restrictions for each benefit to maintain a non-MEC status would allow the owner to make a more informed decision, in the event that multiple benefits are affected.

Effect of the QAB on Reduction Retesting under the Alternative Method

The alternative method essentially reflects the change in the QABs by setting a minimum death benefit that is allowable without creating a MEC status. At first it seems non-intuitive, and even may seem incorrect, to increase the MinFace and RIBFace by a reduction in the QAB. Since the RIBFace is only used to determine a MEC Status, this process is reflecting the “cost” of reducing the QAB as a constraint on any death benefit reductions.

The alternative method of dividing the RIB test into three steps, however, relies on the premise that the use of a minimum benefit is equivalent to the testing of premiums. The RIBFace and MinFace determinations are only used as a measuring device for determining MEC status. These amounts are used to determine the amount of funding that would be allowed under the Seven-Pay test. For policies that are determined to not be a MEC, exact benefit calculations are required to determine the Seven-Pay values and monitor the policy on a going-forward basis.

For the QABs specifically, the reflection of the change in the “cost” of the QAB (present value of charges) can be measured identically through either a change in the SPP or through the increase in the MinFace. This allows for the determination of MEC status independently from the determination of compliance of the policy under the 60-day rule or the resetting of values if a non-MEC.

An example may provide some insights as to the relationship of the death benefit and QAB.

Example: Termination of a QAB in a policy that paid premium equal to the SPP

Consider a policy with a QAB, where the actual premiums paid equal the SPP at issue, including the value of the QAB. Then assume that the policy terminates the QAB entirely, triggering the RIB test. In essence, the SPP is being recalculated at issue on the assumption that the only benefit is the death benefit.

Following Equation 6 above, and recognizing that the PV(QAB) is now worth zero, an application of both Equation 3 and 6 results in the following:

Some observations may help:

- As the policy was fully funded to the Seven-Pay limit, the MinFace and RIBFace at policy issue equals the policy’s actual death benefit.

- The MinFace and RIBFace therefore will increase by the value of the QAB charges that were paid for in the combined premium paid towards the Seven-Pay limit.

- The resulting benefit is the death benefit that would have been solved for if the policy paid the same premium (SPP) into a policy without the QAB.

This example demonstrates how a QAB provides both extra funding and how that funding, if paid, limits the amount of death benefit reduction that is possible.

It also suggests a possible administrative practice. Insurers are often asked to solve for the Seven-Pay benefits based on a given assumed premium paid. It is possible to solve for the Seven-Pay death benefit using the assumed premium as the SPP, but assuming that there are no QABs present. If the policy’s death benefit were set at this higher level, the corresponding Seven-Pay limit would be higher by the value of the additional QABs selected. The owner would then be given a choice: If they pay a higher premium (up to the Seven-Pay limit which includes the QAB), then there is an understanding that the QAB cannot be removed without causing the policy to become a MEC. Alternatively, they can pay their original assumed premium with the understanding that the policy could decrease the QAB without causing a MEC status to occur when RIB testing is performed.

To demonstrate this practice, consider a Male Age 50. They are planning on a QAB that has a charge of $120 per year until age 100. Their budgeted premium is $10,000 per year and they are asking for a face amount to support this at the minimum allowable face amount under the Seven-Pay test.

The company can solve for the face amount without reflecting the QAB. Using the same formula as MinFace, with an APP of $10,000 and no PV(QAB), the face amount would equal $122,000 (rounded for this article). Once the policy is placed, the actual SPP, including the QAB, is $10,425 (rounded). The contribution of the QAB to the SPP is therefore $425. The owner has a choice:

- If the owner pays the $10,000, then they have the option to reduce or discontinue the QAB and the policy would not be a MEC upon a reduction retest.

- If instead, the owner pays $10,425, the owner would not be able to reduce the QAB benefit during the testing period without being classified as a MEC.

This is an example of how the “cost” of the QAB can be measured by the impact it has as a limitation to the minimum benefits under the policy.

Step 2: MEC Re-compliance with QABs

The determination of whether a policy can be brought into compliance under Section 7702A(e)(1)(B) is the same as is described in Part 1 of this series. This process is the same with or without a QAB on the policy.

Under the traditional method, the comparison of the premium history to a reduced Seven-Pay limit is performed. This allows for an exact determination of the first premium that would violate the Seven-Pay test, and if it is within the prescribed 60-day period the policy can be re-complied.

Under the alternative method, the policy is first screened to see if it is within a 60-day period. If not, the policy is marked as a MEC. If the premium is within the 60-day period, then the premium history is retrieved and exact testing can be performed similar to the traditional method to determine the amount of refund to the owner. Doing so reduces the amount of data and retroactive testing that is used, until it is determined that this data is necessary.

Step 3 Non-MEC Testing Limits with QAB

If the policy is determined to not be a MEC, then the same procedure exists for both the traditional and alternative methods. In such a case, the Seven-Pay limit is calculated assuming the applicable reduction in both the death benefit and any QABs. This is done using the insurer’s existing systems. These values are then used to monitor the policy on a going-forward basis.

Further Observations

Both the traditional and alternative methods presented in this series provide for an insurer to be able to monitor policies for a RIB test and determine if the policy would be a MEC.

The traditional method provides for a single step to determine if the policy would be a MEC, the amount of any refund to bring the policy into compliance, and the limits to use going forward. To do so the insurer must have the full premium history available for a policy at any point in time.

The alternative method breaks down the RIB test into three different steps. There are some advantages in this approach:

- MEC Determination does not require a retroactive recalculation of Seven-Pay values. Rather, it relies on a cumulative premium to-date and a minimum benefit package that would allow the policy to be a non-MEC. Retroactive recalculation is needed in the event that MEC status can be reversed within the allowable 60-day testing period.

- The method does not require the full premium history. This reduction in the data needed can be very useful in administrative or illustration systems.

- The ability to decompose the benefit reductions by each benefit being reduced allows for the policy owner to understand the relative impact (“cost”) that each benefit has on the Seven-Pay test.

- A comparison of the RIBFace to the actual death benefit allows the owner to be provided with what the allowable reduction in death benefits can be, given the reduction in the QABs.

RIB testing is one of the most complex processes for monitoring policies for compliance under Section 7702A. Insurers have systems and administrative practices to monitor compliance as well as contracts and disclosures to explain the consequences of reductions to policyholders. The alternative method provided here may be useful to insurers to enhance their current practices.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the Society of Actuaries, the editors, or the respective authors’ employers.

Larry Hersh, FSA, is an actuary who has focused on product tax compliance and product design. He can be reached at lmh.j.mail@gmail.com.